The health ministry was able to rapidly scale up COVID-19 testing when the second wave of the virus first broke, but since the wave turned to a flood it has struggled to stay afloat.

By FRONTIER

On September 30, Myanmar announced a record 946 COVID-19 cases in a single day. Less noticed was that it also performed a record number of lab tests – 6,262, to be exact.

As cases have increased, particularly in Yangon, numbers like this have quickly become the norm. In response to the second wave, the country’s various testing facilities have had to ramp up from processing around 2,000 samples a day at the end of August and are now regularly exceeding 5,000 tests a day, ministry figures show.

“The main priority is testing the primary contacts [of COVID-19 patients], patients under investigation, and people leaving quarantine sites to make sure they are clear,” said Dr Than Naing Soe, health ministry spokesperson and the director of its Health Literacy and Promotion Unit.

Leading the way is Yangon’s National Health Laboratory, which is routinely carrying out 2,500 tests or more a day – close to half the national total. Around 80 staff work in two shifts to process samples around the clock using RT-PCR testing equipment, including the Cobas 6800.

But the rapid rise in cases in Yangon has quickly stretched testing capacity to breaking point.

As a result, Frontier understands that the Ministry of Health and Sports has been unable to consistently stick to its testing policy released in May, which expanded the eligibility criteria to include all medical personnel working with COVID-19 patients, all medical personnel and volunteers at quarantine centres, and all people in quarantine centres. Reports have also emerged of people with COVID-19 symptoms being turned away from hospitals because they have no space for them, which could result in them not being tested.

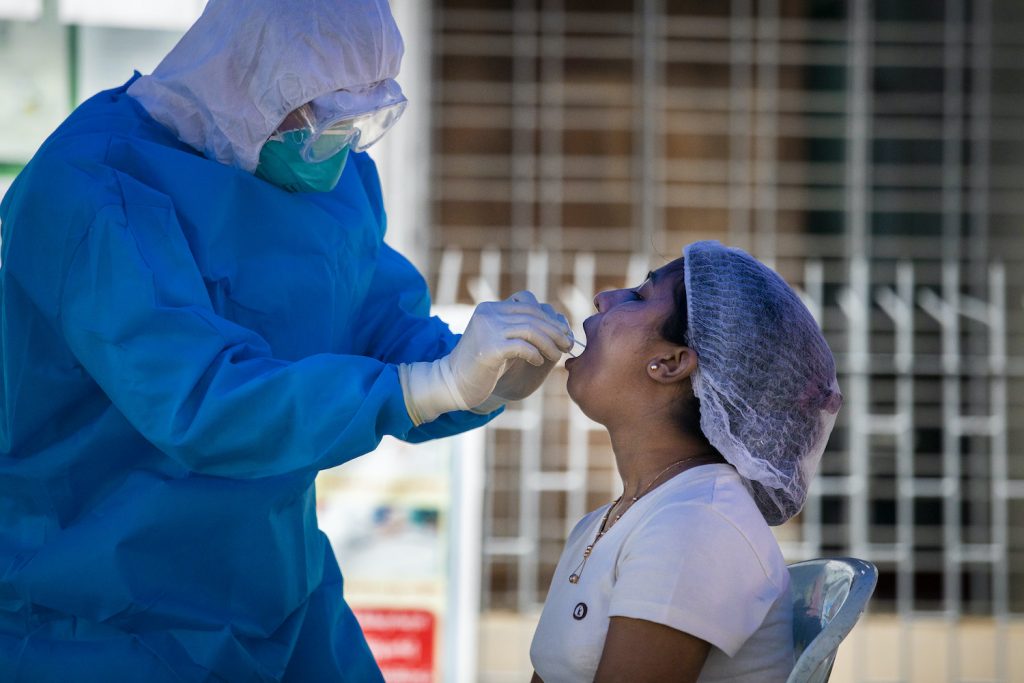

Read more: ‘The disease still scares me’: A day with the COVID-19 testing team

In a virtual meeting with Minister for Health and Sports Dr Myint Htwe on September 24, members of the Yangon Region Coordination Committee on COVID-19 Prevention, Control and Treatment acknowledged testing facilities in the city are “running beyond their capacity”.

Dr Khin Khin Gyi, director of the Central Epidemiology Unit, said the ministry had relatively few options for significant increases in testing capacity.

“Testing a much larger number [than is currently being done] will be impossible,” Khin Khin Gyi told Frontier. “Our country has limited resources.”

That’s bad news for those hoping for a quick end to stay-at-home orders that are in force in Yangon and Rakhine State.

Without adequate testing, it’s impossible to properly understand the pandemic and stop the virus from spreading. Unless you know who is infected, you can’t isolate and treat cases, or trace and quarantine close contacts.

One glimmer of hope lies in the deployment of 200,000 rapid antigen test kits from South Korea, which were sent out to local hospitals at the end of September. The tests can provide results in as little as 30 minutes and are said to be 95 percent accurate.

If Myanmar is unable to scale up testing, it will instead have to rely heavily on harsh restrictions on movement and contact to bring the outbreak under control – at great social and economic cost.

Stretched to breaking point

Myanmar’s laboratories can process around 6,000 RT-PCR tests a day, while recently deployed GeneXpert machines can potentially conduct a further 300 to 500 tests a day. But with the caseload centred on Yangon, not all that capacity can be used – it’s not practical, for example, to fly swabs from Yangon to be tested using a GeneXpert in the Kachin State capital Myitkyina.

The shortfall in testing capacity is evident in Ministry of Health and Sports data. The case positivity rate or test positive rate – the number of positives as a percentage of total tests – for September is 9.61pc, and over the past 10 days has averaged about 15pc. The day that Myanmar conducted its record 6,262 tests, the positivity rate was 15.11pc.

As of September 28, only a handful of countries had higher case positivity rates than Myanmar – Iraq, Tunisia, Mexico and a few nations in Central and South America, including Brazil, Colombia and Argentina. Myanmar is also ranked low for tests per million people, among a host of African countries.

These numbers suggest that Myanmar is not testing anywhere near enough. The World Health Organization has recommended as a rule of thumb that countries should aim for between 10 and 30 negative tests for every positive test – in other words, a maximum positivity rate of 10pc.

A high percentage of positive tests indicates high infection rates in the community. In May, the WHO recommended that governments only consider lifting restrictions if the case positivity rate stays below 5pc for at least two weeks.

As experts from Johns Hopkins University wrote in August, “A high percent positive means that more testing should probably be done – and it suggests that it is not a good time to relax restrictions aimed at reducing coronavirus transmission.”

The challenges in quickly scaling up testing capacity mean that Myanmar will likely have to keep Yangon and other areas of the country under stay-at-home orders and preserve other restrictions for some time to come.

It is difficult to know exactly what the positivity rate is in Yangon because the health ministry does not disaggregate this data by state or region.

The ministry has also not conducted antibody testing on a random sample of the population in Yangon to get an accurate picture of infection within the community.

There are indications though that infection rates in Myanmar’s largest city are likely significantly higher than the national data suggests.

At the main laboratories in Yangon, the NHL and Department of Medical Research, the case positivity rates have been closer to 25pc, while at the laboratories in Mandalay and Mawlamyine the rate has been lower, pulling down the national average.

At a “fever clinic” in Yangon’s Insein Township that has begun collecting swabs from suspected COVID-19 patients, the positivity rate has been as high as 80pc, Dr Mar Mar Kyi, a senior consultant physician at Insein General Hospital who helps run some of the fever clinics, told Frontier. Of the 130 samples taken over four days in September, 71 were positive.

A slow start

Still, the level of testing during Myanmar’s “second wave” marks a major improvement on the first outbreak earlier in the year. The NHL only began testing on February 20 and until the start of May the country was conducting just a few hundred tests a day.

Several factors kept testing low at the time. Government policy, for one, restricted who was eligible to be tested – incoming migrants and those who’d recently travelled to COVID-19 hotspots, for instance.

Some critics at the time claimed the government was intentionally limiting its testing regime to keep the number of cases artificially low – claims it denies. But the government’s hand may have been forced; even with new machines, labs lacked adequate additional resources, such as chemical reagents and trained personnel to process the tests. Initially there were just a dozen staff at the NHL scrambling to process tests coming in from across the country.

Gradually, Myanmar overcame its resource crunch and ramped up testing. New equipment came online – including several Swiss-made COBAS 6800 machines capable of processing up to 1,300 tests a day – and additional staff were trained. Testing kits and reagents arrived in the country, and the health ministry changed its criteria to test more widely.

Invest in Frontier Myanmar’s independent journalism by becoming a member. Sign up here.

By early June, Myanmar had six laboratories testing for COVID-19, including the NHL, the Department of Medical Research in Yangon, the No. 1 Defence Services Hospital in Yangon, the No. 2 Defence Services Hospital in Nay Pyi Taw, and public health laboratories in Mandalay and the Mon State capital Mawlamyine.

But by this point, most local transmission appeared to have stopped. Instead, testing was focused on those returning from abroad, and those at high risk of exposure, such as some health workers and volunteers.

Actual capacity was significantly higher, so when new cases of local transmission emerged from Rakhine State in mid-August and spread to Yangon – the start of the country’s “second wave” – health authorities could quickly scale up the number of tests being conducted.

NHL deputy director general Dr Htay Htay Tin said the NHL has recently been testing more than 2,500 samples a day, while nationally the number is more than double that.

She said that adherence to government orders and advice would be essential for bringing the outbreak under control.

“We can do more testing if the number of cases increases,” she said, “but to prevent that from happening, the people must rigorously follow the directives and instructions set out by the Ministry of Health and Sports.”

Rolling out testing

In April, the health ministry announced plans to decentralise testing to hospitals around the country in order to expand capacity and speed up the process.

When Myanmar’s second wave emerged in August, the ministry had just deployed new GeneXpert machines at 27 district hospitals throughout the country. As a result, samples no longer had to be sent long distances to be tested at laboratories in Yangon or other major cities.

Cepheid, the American manufacturer of the GeneXpert – which have previously been deployed to test for hepatitis and HIV, among other diseases – claims they can return a positive COVID-19 test in as little as 30 minutes. In March, the United States Food and Drug Administration granted emergency authorisation for their use in COVID-19 testing. Several other countries have since followed suit

“The GeneXpert tests are highly accurate and work by detecting the unique genetic profile of the COVID-19 virus,’’ Australia’s health minister said in a statement on June 1, adding that results can be achieved within an hour.

Each hospital with a GeneXpert can conduct between 16 and 64 tests a day, depending on the module supplied with the machine.

“The NHL had trained state and regional health staff in the use of GeneXpert machines before the second wave struck, and the district hospitals have been able to implement the new testing quickly,” Khin Khin Gyi said.

The NHL checked the efficacy of each district hospital’s use of the GeneXpert system by sending each of them 10 positive and 10 negative COVID-19 samples.

“If the test results matched those of the NHL, the district hospital was approved to conduct testing,” said Htay Htay Tin said.

While all 27 hospitals have passed the test, she said only 20 have so far conducted tests with the GeneXpert machines, as the rest have not yet had a suspected case to test.

Read more: Swabs, staff and supply chains: How Myanmar cleared resource hurdles to ramp up COVID-19 testing

Dr Sai Win Zaw Hlaing, chief of Rakhine State’s Public Health and Medical Services Department, said that NHL staff had trained lab workers at the Sittwe and Kyaukphyu district hospitals on the GeneXpert machines before they began using them. Sittwe hospital can now conduct more than 100 tests a day and Kyaukphyu hospital almost 80 tests a day.

Before the GeneXpert machines were installed in Rakhine, swabs from the state had to be sent to Yangon. During one such trip in April, a WHO driver was killed in Rakhine State after his car was fired upon by unknown gunmen.

Sai Win Zaw Hlaing said increased local testing capacity has been essential to containing the COVID-19 outbreak in Rakhine, as the faster turnaround on test results has meant the state health department could quickly identify cases and carry out contact tracing and quarantining.

“We plan to extend COVID-19 testing to Mrauk-U and Maungdaw district hospitals too,” he told Frontier on September 20.

In another example of testing decentralisation, some “fever clinics” have also started taking samples. The first of these clinics were set up in early April to screen suspected patients for COVID-19-like symptoms and ease the burden on hospitals. Twenty-one fever clinics are operating across Yangon with the support of more than 100 volunteer doctors and nurses and 70 community volunteers.

The clinics have mostly been referring suspected cases to hospitals for testing, but on September 11 the ministry launched a pilot project at an Insein fever clinic to begin collecting swab samples on site and sending them to the NHL.

Mar Mar Kyi, the senior consultant physician who helps run some of the clinics, said swab samples are being collected on two of the four days the Insein clinic is open, and that they’ve been collecting between 40 and 90 swabs a week.

The clinic is swabbing suspected COVID-19 patients, including those who’ve been in contact with confirmed cases and anyone referred there by a township official.

“North Okkalapa fever clinic is also implementing this project, and we are talking to public health professionals about expanding it to South Dagon, Thanlyin, Hlaing Tharyar and Ahlone townships,” said Mar Mar Kyi, who helped to set up the first fever clinic.

Rapid test kits arrive

With laboratories in Yangon at full capacity, the health ministry has looked at a range of options to further boost daily testing rates. During the September 24 meeting with the health minister, the regional COVID-19 committee suggested several options for increasing testing. One option under discussion is a fleet of “mobile lab vans” than can collect samples and send them from Yangon to the labs in Mandalay and Mawlamyine, where the numbers are drastically lower and the labs are far from strained.

Than Naing Soe said the ministry plans to buy another Cobas 6800 machine, although it’s not clear when it will be purchased or where it will be installed. It also plans to expand testing in Shan State by opening a new laboratory in Lashio in November, to go with the lab that opened in the state capital Taunggyi in September. “When Taunggyi and Lashio are both operating, we’ll be able to conduct another 1,000 tests a day,” Than Naing Soe said.

But it’s the arrival of antigen kits that provide the best opportunity to increase testing quickly. With case numbers rising, the government took the decision to order the kits from South Korea on September 20, Frontier understands, and little more than week later they were already being deployed.

Although antigen test kits are less reliable than RT-PCR tests, and work best on patients with a high viral load, they also have a number of advantages – including cost, speed and portability – that make them ideal for a short-term testing surge.

State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi said on September 28 that 60,000 have already arrived and another 140,000 were due to arrive the following day. The testing kits are being sent to township and district hospitals to reduce the burden on larger specialist hospitals, which have struggled to cope with the large number of suspected cases.

In an earlier speech, Aung San Suu Kyi said that the large number of people seeking testing at specialist hospitals was causing difficulties, and urged those with possible COVID-19 symptoms to instead go to township or district hospitals where the antigen kits have been deployed. She also requested local GPs and doctors from government and private health facilities to help these hospitals administer the tests.

Aung San Suu Kyi cautioned that the antigen test kits would likely cause an increase in the number of confirmed cases, but that this should not be cause for alarm. “Don’t lose hope if you are tested positive. When we know the result, we can give the treatment earlier and the recovery rate will be increased,” she said.