Transport and logistics companies are questioning the ban on trucks on the Yangon-Mandalay Expressway, arguing that it costs time and money and puts lives at risk.

By THOMAS MANCH & KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

LAST MONTH, Mr Paul Apthorp drove up and down the Yangon-Mandalay Expressway, a four-lane highway that links the country’s two main cities. There were many times, he said, when he couldn’t see another vehicle in either direction.

Yangon residents might find the open roads a relief after the city’s traffic jams. But as vice chairman of the GMS Freight Transport Association, a regional coalition of transport companies, all Apthorp could see was a missed opportunity.

His reaction: “What an absolute waste.”

Apthorp is one of a growing number of leaders in Myanmar’s logistics and freight sectors calling for the expressway to be opened to trucks – a move they say would improve transport efficiency, reduce freight costs and save lives.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The Asian Development Bank estimated last year that allowing trucks on the expressway would immediately save US$110 million a year – more than 10 percent of total road freight costs. With some additional investment in the road this figure could rise to $200 million, it said in a policy note prepared for the Ministry of Transport and Communications. Over 15 years, the amount saved could be as much as $10.7 billion, for a benefit cost ratio of 18.5. Unsurprisingly, opening the highway to trucks was the top recommendation in its policy note.

A 2014 Japan International Cooperation Agency survey for the National Transport Development Plan reached the same conclusion, recommending the expressway be opened to trucks before 2018.

The underuse of the expressway is particularly striking in Myanmar because the country is so bereft of high-quality transport infrastructure. The ADB said in 2016 that US$45 billion to $60 billion would have to be invested in transport over the next 15 years.

tzh_ygn-mdy_highway8.jpg

The Yangon-Mandalay Expressway is mostly closed to trucks despite being well below capacity. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

For Apthorp and other proponents, allowing trucks on the expressway is a no-brainer.

“They [the government] have to see the economic benefit of it,” Apthorp told Frontier.

For now, though, the government is standing by its policy.

Old vs new

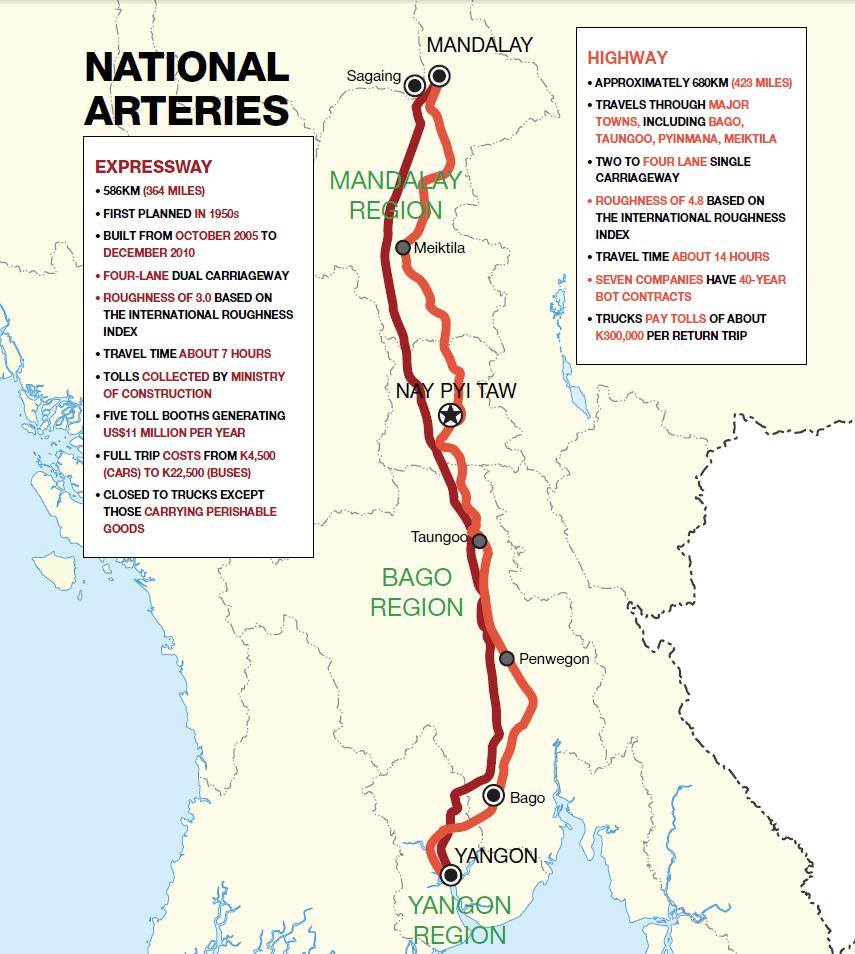

Because of the ban, much of the country’s truck fleet – which shifts 90 percent of its freight – can be found just dozens of kilometres east of the expressway, on the Yangon-Mandalay Highway.

This route is 10 percent longer and passes through large towns, such as Bago, Taungoo, Pyinmana and Meiktila, as well as countless villages.

As a result the return trip typically takes about three days, where it could be done in a day on the expressway with two drivers.

Transport companies are adamant there is no good reason to restrict freight to the old highway when the newer expressway sits underused.

The ADB concurs, with its policy note from 2016 stating there was “no strong reason” to restrict trucks to the old highway, “which is longer and in poorer shape”.

expressway-infograph.jpg

Mr Adrien Veron-Okamoto, a Southeast Asian transport specialist at ADB, confirmed that the ADB was not aware of any reason for restricting trucks on the expressway.

“There’s definitely a cause for opening the expressway to trucks,” he said.

Veron-Okamoto said ADB was in talks with the government about policy and financing safety improvements to the expressway.

A 2015 tender to fund upgrades through a build-operate-transfer contract received only 20 tender proposals, Eleven reported at the time, and the plan appears to have been abandoned.

Industry sources said one reason they have been given was that trucks would damage the expressway but there is little evidence to support this.

Most of the country’s trucking fleet is 12-wheel imported Japanese vehicles that operate at up to 27 tonnes gross weight. The expressway can withstand 80 tonnes, according to a December 2010 report in the state-run New Light of Myanmar.

The highway is also open to express buses, which carry more load per wheel than a 22-wheel semi-trailer with a gross weight of 48 tonnes.

“The buses that are on [the expressway] at the moment are really trucks in disguise,” said Yoma Fleet general manager Mr Allan Davidson. “They are sometimes full of passengers, and under the seat, the whole bottom is just full of freight.”

Safety concerns

Ministry of Construction director U Kyaw Naing said the reason was safety. The expressway is a dangerous road, he said, and if heavy trucks were allowed there could be more accidents involving buses and family vehicles. Because the old highway is narrower, truck drivers can’t exceed the speed limit.

He said the ministry was aware of the ADB’s recommendation and projection on savings but believed that safety concerns were more important.

He also said that trucks carrying perishable or time-sensitive goods, such as fruit, vegetables and newspapers, are allowed on the expressway with prior permission.

img_6947.jpg

Highway buses are allowed on the expressway despite having a similar axle load as trucks. (Thomas Kean | Frontier)

The Yangon-Mandalay Expressway is often referred to as the “Highway of Death” because of the frequency of fatal accidents. However, freight companies insist the old highway is more dangerous for road users because it is narrower, in poorer condition and passes through heavily populated areas.

The police force could not provide figures to make an assessment on this claim. The figures do show that deaths on the expressway are declining, possibly due to safety awareness campaigns. From January to the end of October this year 99 people died on the expressway, down from 134 over the same period last year, according the Highway Police Force.

But Veron-Okamoto from the ADB said that it would be safer for road users if trucks used the expressway rather than highway. The ADB’s own engineering assessment found the newer road generally sound, with limited repairs and safety improvements required.

Taking a toll

Transport industry leaders say they suspect the reason is that the Ministry of Construction is protecting the interests of the companies that collect tolls on the old highway.

Seven companies – Oriental Highway (formerly Asia World), Max Myanmar, Shwe Than Lwin, Shwe Taung, Kanbawza, Yuzana and Thawdawin – control the highway under build, operate and transfer (BOT) contracts.

State media reports indicate that private companies began upgrading the highway in the early 2000s. According to an August 2002 article, companies involved included Shwe Than Lwin, Asia World, Olympic (a forerunner of Shwe Taung), Kanbawza, Yuzana, Hong Pang and Dagon International.

It is unclear when the BOT contracts were signed. Max Myanmar’s website states that it began collecting tolls on the Taukkyant to Bago section on April 1, 2008. According to the ADB, most of the country’s BOT contracts for highways have a 40-year duration.

Davidson from Yoma Fleet told Frontier that the deputy minister for construction had advised his deputy manager there was “an understanding” with the toll operators that trucks would not be allowed to switch to the expressway.

CEA Logistics country manager Mr John Hamilton said he had also been told by the ministry that there was “understanding” between the government and the toll operators.

“I don’t know how much these toll road companies paid for these licences, but the government is obviously apprehensive of taking the trucks and the money away from these toll operators,” he said.

Hamilton said his drivers pay K290,000 in tolls for each return journey between Yangon and Mandalay – over 25 percent of the trip’s total cost.

“It’s costing us time, money, environmental impact, safety,” he said. “On the expressway we could pay the same toll, but still get double the productivity.”

Kyaw Naing, the Ministry of Construction director, said there was no informal understanding with the toll road operators. He also confirmed there was no provision in the BOT contracts that trucks must remain on the old highway.

Nevertheless, the fact that the companies are considering significant upgrades to the old highway suggests they are confident that income from tolls will continue to flow.

img_6960.jpg

The Ministry of Construction collects tolls on the Yangon-Mandalay Expressway. (Thomas Kean | Frontier)

Australian engineering firm SMEC confirmed that it had been engaged by “a private company” to investigate the feasibility of safety improvements to the Yangon-Mandalay Highway. SMEC Myanmar water infrastructure manager Mr Jonathan Carroll said the impact of opening the expressway to trucks was not part of the study.

Ministry of Construction deputy director Daw Thazin said any decision to invest in additional lanes was up to the toll companies.

Shwe Taung chief executive officer U Aung Zaw Naing said the companies that operate the old highway are progressively upgrading it from two lanes to four lanes where possible.

“Because it’s an old highway, some of the areas we cannot extend because of houses, so some is three lane,” he said.

He confirmed there was nothing in the BOT contracts keeping trucks on the highway. Shwe Taung would not object to a change in policy if it was good for the economy, he said, adding that both roads were important infrastructure assets.

“That totally depends on government policy,” he said. “As long as the [policy] is supporting the growth of the economy by making the logistic costs down, we would be very happy” for trucks to be allowed on the expressway.

But another highway company was less enthused about the idea.

In an emailed response to questions, Kanbawza Group’s managing director U Moe San Aung said trucks “should not be allowed on the expressway”.

Kanbawza did not respond to requests for further clarification.

A proposal for change

Yoma Fleet and CEA Logistics have put together a proposal for semi-trailer trucks to be allowed on the expressway but only if they meet certain requirements.

Davidson said they should be left-hand-drive with trailers that meet ASEAN specifications, be limited to 100km an hour, and have 800km capacity fuel tanks so they don’t need to refuel between destinations. Drivers would be required to complete defensive driving courses every two years. Trucks would be restricted to entry and exit at Hlegu in Yangon Region, Nay Pyi Taw and Mandalay.

Yoma Fleet stands to benefit from such an arrangement. The company leases about 600 trucks nationwide, including cement rigs, line haul trucks and an assortment of two-tonne light trucks.

But Davidson insisted that the campaign for policy change is about more than money. In October, he said, one of his company’s trucks killed a motorcyclist on the old highway; the rider had tried to overtake and collided head-on with the truck. Such accidents are far less likely on the expressway, he argued.

“The death and carnage everyday on it is real sad to see,” he said. “It’s really just wrong.”

Mr Howard Seargent, managing director of warehousing and transportation company Kospa, said banning trucks from the expressway was an opportunity squandered.

“We just encourage the authorities to really look at this as closely and quickly as possible,” he said. “Let’s see how we can get this off the ground.”