Snap rule changes and snails-pace processing mean truck drivers have at times been forced to wait for days at checkpoints on Myanmar’s major trucking routes during the country’s “second wave” of COVID-19.

By HTIN LYNN AUNG | FRONTIER

In early October, the Mandalay Region government almost single-handedly brought Myanmar’s logistics sector to a screeching halt.

In response to rising COVID-19 cases in Yangon, it introduced a new rule: truck drivers could only enter the region if they had passed a COVID-19 test within the past 72 hours.

When this rule was introduced, hundreds of trucks were already on their way from Yangon to Mandalay – the country’s busiest trucking route, accounting for 30 percent of traffic.

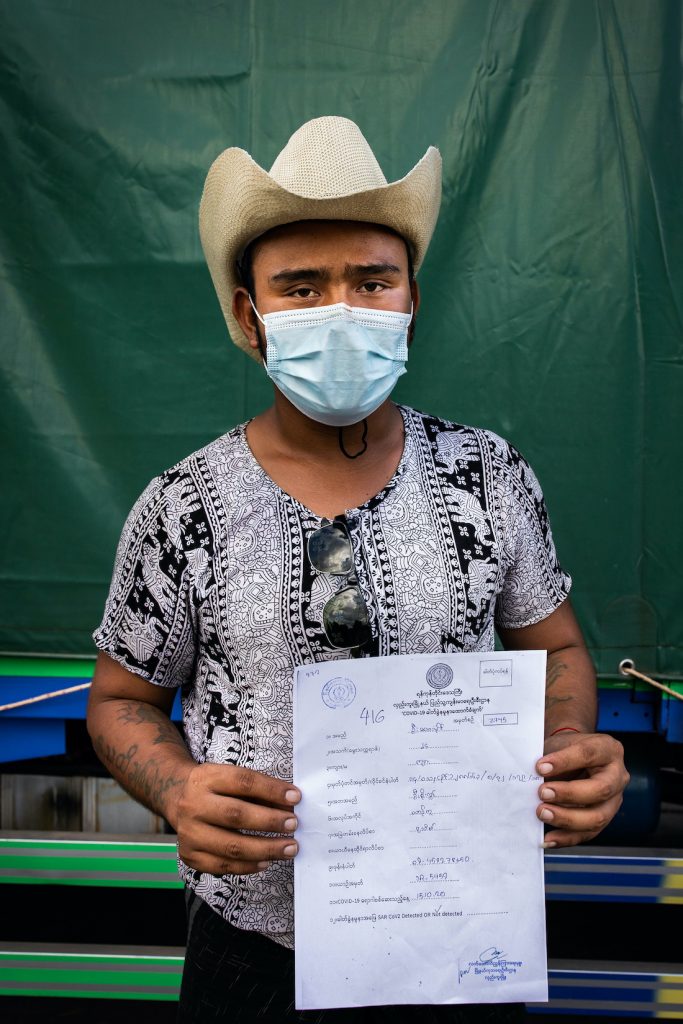

The drivers and their assistants had health certificates saying they had no COVID-19 symptoms, but these were different from the COVID-free certificates Mandalay Region officials were demanding. When the trucks got to the checkpoint at Yamethin Township in southern Mandalay Region they found their path blocked. Tempers flared; 13 drivers who got into an argument with COVID-19 committee officials at the gate were arrested and later sentenced to 45 days’ imprisonment for disobeying official instructions.

Within days of Mandalay Region announcing the restrictions, more than 1,000 trucks had become stranded at the Nyaung Lun gate, creating a line that stretched back some 10 kilometres. Drivers frantically called truck owners for advice; many abandoned their vehicles completely.

As news spread of the restrictions, fewer and fewer drivers were willing to make the trip to Mandalay. Prices to send goods between the two cities began to soar, and finding a truck at all was difficult for weeks, said Mr Simon Howett, chief business officer of Karzo. The company links clients with trucks from its “virtual fleet” of 4,500 vehicles based on their needs and budget. “Our team were going around the trucking gates trying to find suppliers, running around until late at night,” he said. “Really, it was like trying to find water in the desert.”

The jam slowly began to clear as health officials started testing drivers and assistants at the gate using rapid test kits. But such was the congestion that it took more than a week for many of the trucks to pass through the checkpoint, and more than two weeks for the situation to return to something like normal.

“All truck drivers are facing difficulties,” U Kyin Thein, chair of the Myanmar Highway Freight Transportation Service Association, said on October 7. “There are health checks everywhere and drivers are afraid that they’ll be found violating the rules or test positive. There’s not enough staff at the toll gates to handle all the trucks, so there are long jams … it’s hard to say where the worst place is, because it’s happening in so many places.”

While increased testing has been rolled out, lengthy delays are still a common occurrence at toll gates and some drivers are refusing to return to work, Kyin Thein told Frontier. “A big problem is that COVID-19 rules still vary from place to place. When that’s the case, few drivers will want to work.”

Second wave blues

Myanmar’s COVID-19 second wave has had a much more far-reaching impact on the logistics sector than the first outbreak earlier this year.

Although truck drivers had to navigate curfews and other restrictions that made their journeys longer and increased costs for customers, the logistics sector was largely able to keep moving in April as the rest of the country shut down to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

But the increased severity of the second wave, and the response measures from the national and regional governments, has placed great strain on the country’s trucking fleet, which moves about 90 percent of all freight.

Shortly after the virus re-emerged in Rakhine in August, national and regional governments began introducing restrictions to curb its spread that significantly hindered freight movements.

Governments introduced mandatory 21-day quarantine for anyone crossing state and region lines, forcing trucking companies to swap drivers at the border or even unload goods and put them onto another truck.

As the consequences of these policies became clear, the National-Level Central Committee for Prevention and Control of COVID-19 was forced to intervene. On September 20, it issued a letter setting out 16 rules to ensure the smooth flow of commodities.

The rules required states and regions to allow truck drivers to enter if they have passed a COVID-19 test within the previous two weeks, and forbid drivers or their assistants from leaving highways, meeting or eating with locals, or stopping outside of designated locations.

But Myanmar’s limited testing capacity made enforcing this policy difficult. Until the end of September, it could conduct a maximum of only 6,000 tests a day at laboratories, which used the highly accurate but slow RT-PCR method.

The arrival of hundreds of thousands of antigen rapid test kits from the end of September was a game changer, enabling decentralized testing and in far greater numbers. But rollout to trucking checkpoints has been slow, and lack of staffing has hindered the administering of tests to drivers and their assistants.

Race against time

Drivers who managed to get a COVID-19 test began facing a new problem. On October 1, the government changed the rules so that the result was only valid for 72 hours. With a 10pm curfew in force and long delays at checkpoints, it was almost impossible to complete a return trip on any of the major routes within that timeframe, requiring them to take a second test.

“It’s difficult enough just to get to Taunggyi in 72 hours – we are really racing against the clock,” driver Ko Wai Yan Tun told Frontier as he waited for a test at Zero Mile on the Yangon-Nay Pyi Taw Expressway on October 24.

There are several checkpoints along the way to Taunggyi, the Shan State capital, but the longest wait is at Nanpantet in Kalaw Township, at the entrance to Shan. “It can take up to two days. Some truck drivers can’t reach the gate from Yangon in 72 hours so they aren’t allowed to pass through. But then everyone else in the line gets stuck behind them. It’s a nightmare.”

As at Yamethin, tensions have sometimes boiled over due to the long wait. The Kanbawza Tai News Agency reported that on October 12 some drivers removed the barriers on the road and simply drove through the checkpoint. More than 100 drivers are thought to have passed through without being examined; eight were subsequently caught and face charges under the Natural Disaster Management Law, the report said.

The situation is little better for drivers travelling between Yangon and the Kayin State town of Myawaddy on the Thai border, another major trucking route. The biggest bottleneck is at the Sittaung Bridge between Waw Township in Bago Region and Mokpalin in Mon State’s Kyaikto Township.

“Even though we get tested and cleared at Zero Mile in Yangon, we are checked again at the Sittaung Bridge and the line is usually so long we have to sleep there. Often it takes 20 hours to get through,” driver Ko Tun Min Oo said. “There aren’t any traffic jams once we get into Mon State.”

U Wunna Aye, who also drives between Myawaddy and Yangon, said the delays had caused great difficulties for his employer, as its contracts state that deliveries have to arrive by a specific time.

“All we can do is apologise to the customer,” he said. “We are always trying to beat the clock because the gates close at different times depending on the state and region, and the rules for health checks are different.”

Some kind of normal

Although the 72-hour rule remains in place, Howett from Karzo said the situation had begun improving from the second half of October as tests became more easily accessible and more trucks returned to the roads.

The resumption of construction, particularly in Yangon, has been important. Cement factories in Mandalay Region and Nay Pyi Taw typically send 500 to 800 trucks to Yangon a day that return to upper Myanmar laden with other goods. But since the closure of worksites in September this fleet had mostly been off the road. “These trucks are such an important part of what you’d call the backhaul, and help to keep prices stable,” he said.

Overall demand remains down 30 to 40 percent year-on-year, Howett said, but he believes the “worst is over”. “We’re certainly expecting to see business pick up as everybody will be trying to make up for lost time.”

But truck driver Wunna Aye said the rules were still frustrating for drivers, particularly the 72-hour rule. “Things went well from November 1 to 15, but then there were big jams at the Sittaung Bridge for five days. Now we see these jams intermittently when a truck at the front of the queue has an expired test certificate.

“All truck drivers have had swab samples taken 15 or even 20 times. Our noses are very sore.”

Two recent developments have made the Taunggyi route particularly problematic for drivers. Since November 23, health authorities at Nanpantet in Kalaw Township have been strictly enforcing the 72-hour rule, where previously they had been showing some flexibility. Compounding the problem, the government stopped allowing trucks to use the Yangon-Mandalay Expressway on November 30. As a result, they are once again confined to the older Yangon-Mandalay Highway, a single carriageway that passes through a number of major towns. “On the old road it takes three-and-a-half days to get from Yangon to Taunggyi,” said driver U Than Toe Aung. “You can’t get there in 72 hours anymore, so drivers have to take another COVID test at the entrance to Taunggyi.”

Kyin Thein said that because of the 72-hour rule many drivers were still refusing to take to the road. “Some are afraid of COVID-19 so they just stay at home, but we have also seen truck drivers arrested and put in jail – many of them are more afraid of the authorities than COVID-19. Only 50 percent of drivers are on the road at the moment,” he said on November 23.

The Myanmar Highway Freight Transportation Service Association has consistently lobbied the government to ease up on the restrictions and ensure rules are set and applied consistently in each state and region, but mostly to no avail. “So far the government hasn’t relaxed the rules for freight transportation,” Kyin Thein said. “We know that COVID-19 cases are increasing, so we don’t want to ask the government to relax things too much. But the situation is difficult for us.”