Solar-power plants are an obvious solution to Myanmar’s electricity shortage. They are faster to build than their fossil-fuel and hydropower alternatives and are cleaner and cheaper to operate.

By DAVID FULLBROOK | FRONTIER

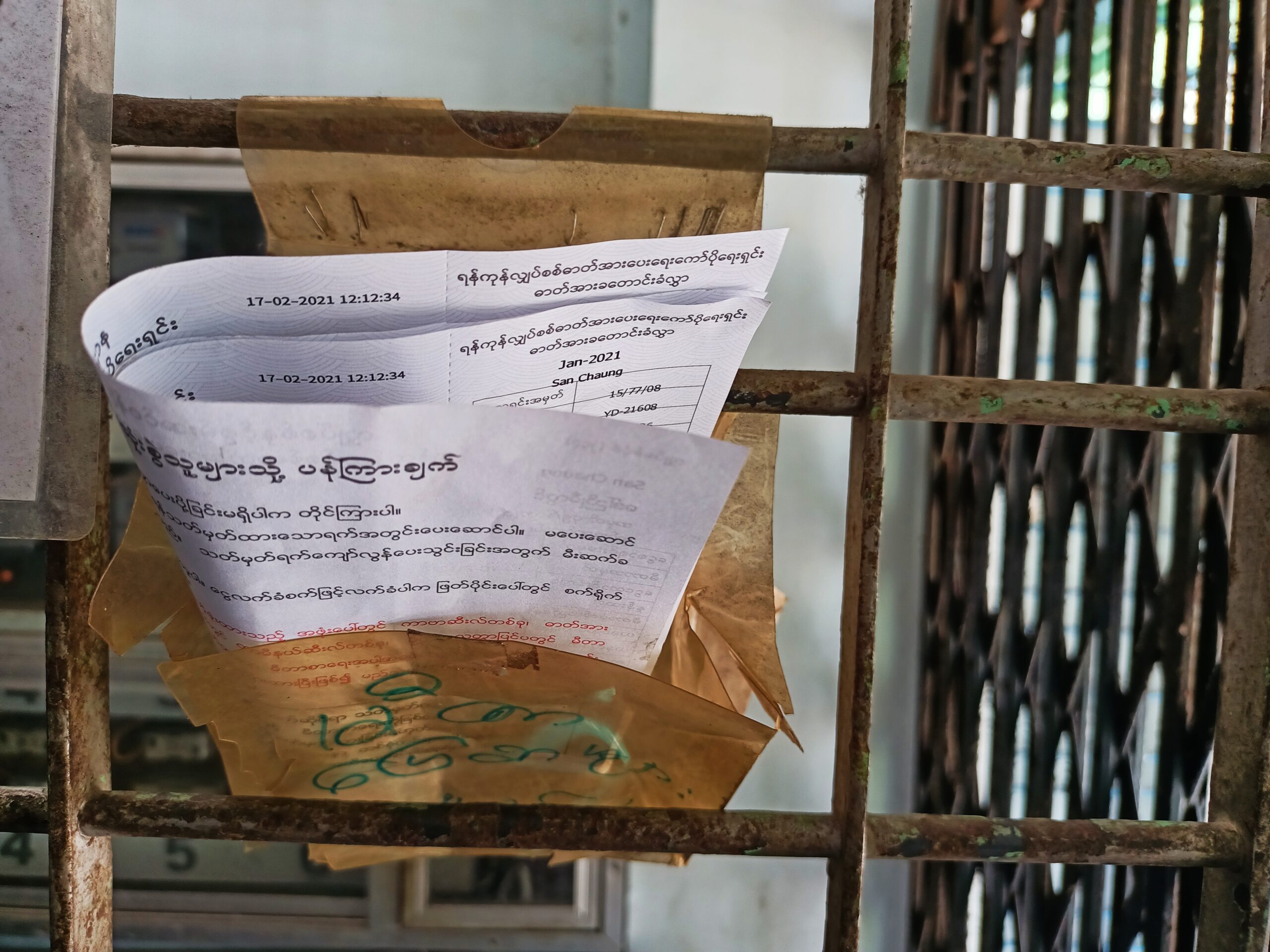

Electricity shortages are again making headlines, with rolling brownouts and blackouts affecting much of the country. Images have circulated on social media that purportedly show the Minister for Electric Power and Energy, U Pe Zin Tun, holding a meeting by candlelight. The image raised questions over the absence of a backup diesel generator, which are usually found at offices, factories and many homes.

The dim light cast by the candles sums up the prospects for an early end to electricity shortages. The hope that a handful of gas-fired and hydropower plants due to go into service in the next few years will provide a reliable supply fades in the face of surging demand, doubling every five years in Yangon alone. In the longer term, an energy master plan prepared for the previous government by the Asian Development Bank envisages mainly coal and big hydropower plants by 2030.

Even if supply was adequate dilapidated transmission and distribution lines present problems. Stressed by soaring demand, transformers and cables often fail. Up to a quarter of the electricity generated by big, distant plants is lost on its journey to homes and factories.

It takes time to fix and expand transmission and distribution networks and to build coal and hydropower plants. If a project proceeds smoothly, a coal-fired power plant might be built in three years and a big hydropower dam in eight years. However, evidence from such projects throughout the world shows that delays and cost overruns are highly likely. The power generation projects least prone to overruns are solar and wind.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

In fact, when it comes to development speed solar leads the way. Competent developers worldwide are building solar projects larger than 100MW in less than a year, or even six months. Similar size onshore wind projects take less than 18 months.

Solar is handily viable on a smaller scale, too, from a single module powering a few lights in a house, to several megawatts generated by panels on a factory rooftop. Furthermore, adding solar close to where people use electricity would also ease demand on the overloaded and worn-out electricity grid.

Prices for solar are also falling. A solar module in 2013 cost 99.99 percent less than in 1956. In the five years to 2015 module prices dropped 80 per cent. Unsurprisingly, solar is booming worldwide, from Thailand to Tanzania, China to California, India to Israel, and supply is rising sharply as fiercely competitive manufacturers bank on economies of scale for profits. Costs fall with scale at a steady rate for solar. That phenomenon, known as the learning rate, can last years, even decades.

Solar has also been given a push in some markets by temporary government subsidies. They help redress market distortions in many countries caused by open-ended direct and indirect subsidies for fossil fuels. Coal, gas and big hydro harm human health and ecosystems, the foundation of food security. Concerns and consequences are already fuelling discord and protests by communities and worried citizens in Myanmar. Such problems are avoided with solar and wind.

There are drawbacks. Solar generates electricity during daytime, usually coinciding with high demand. Output dips if there’s cloud cover. As India’s energy minister has said, the drawbacks are well known and easily manageable. Were they not it is unlikely solar would be growing so fast.

What is stopping solar from taking off in Myanmar where sunshine is plentiful, demand sky high, and diesel-generated electricity is costing up to US$1 a kilowatt-hour? The answer, in a nutshell, is perceptions and policy.

Few realise that solar electricity has already undercut coal, gas and big hydro in many countries. That will be the case everywhere long before solar’s learning rate runs out.

Advances in materials and manufacturing continue to move from laboratories to factories, underpinning prospects for solar costs to fall, even after temporary subsidies end, well into the 2020s. If electricity included all costs, such as effects on health and environmental damage, solar would already be the cheaper alternative by far.

In Myanmar speed matters as much as cost. Diesel generators are fast to deploy, but usually generate the most expensive electricity, without considering other downsides like fumes, noise and fluctuating fuel prices. Gas-fired power plants of up to 50MW can take less than a year to build, but are usually reserved for meeting demand peaks due to high cost. Building solar takes months, or even days.

Perceptions inform policy. Fortunately, preparing policy to encourage the rapid development of solar and wind need not be difficult. Myanmar can learn from the experience of countries worldwide.

It is essential that developers and consumers have clear and simple rules and regulations. Grants and feed-in-tariffs, possibly supported by Myanmar’s international partners, might be helpful but less so as solar costs fall. With a determined effort the regulatory framework, at least for small projects, could be cleared up in months. Getting policy right lowers risk and opens the way to cheaper capital.

There is little to stop the government leading by example to show how fast solar can be installed. The acres of flat roofs in Nay Pyi Taw are ideal for the mass installation of solar modules. It could be done in a few weeks. Why not start at the Ministry of Electric Power and Energy?