While most people living in junta-controlled cities like Mandalay and Yangon have begun paying their electricity bills, a fierce boycott continues in resistance strongholds across Sagaing and Magway regions.

By FRONTIER

In November 2020, Daw May Oo* and her entire family were among the millions that helped deliver Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy a landslide reelection victory. When the military refused to accept the results and staged a coup, she didn’t think twice about joining mass protests.

“We joined every strike we could, including the Silent Strikes and the boycott of bills and taxes paid to the junta State Administration Council,” said the retired teacher.

After the military reacted to mass protests with brutal violence, residents of Yangon found creative ways to resist, including Silent Strikes, when shops across the city refused to open, and refusing to pay taxes or public utility bills.

But at the end of October this year, May Oo’s long-running boycott came to an end, when her house suddenly plunged into darkness.

“At first, I thought the whole neighborhood was blacked out,” she said, but after talking to neighbours, she quickly realised her home had been singled out.

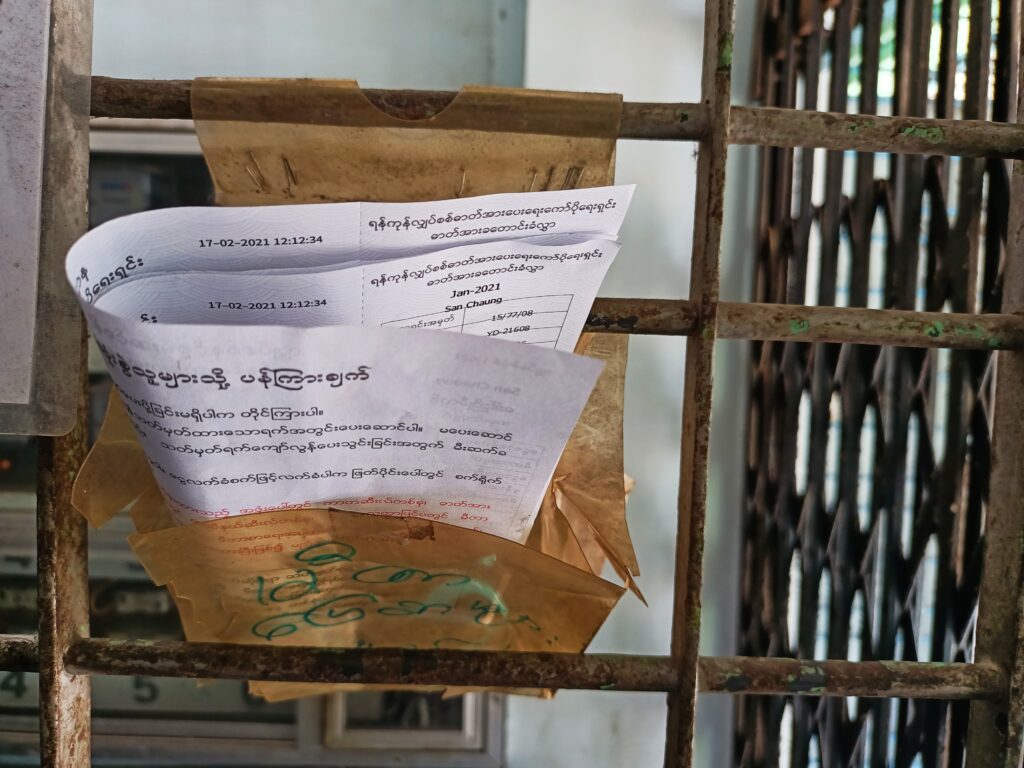

Faced with the prospect of living permanently without electricity, or paying her bill, May Oo finally gave in. She told Frontier her bill had racked up to 2 million kyat, around $975 at the official exchange rate, and she saw many others in the township electricity office that day.

“We persevered until the end,” she said.

Ko Min Kyaw*, an activist with the Yangon University Students’ Union said residents of major cities now have little choice but to pay their bills or face severe retaliation.

“The military council is in control of Yangon and Mandalay,” he said.

The junta ordered electricity officials to step up bill collection efforts starting in April of this year, according to Ko Tun Zaw*, an electrical engineer who has worked at the state-run Yangon Electric Supply Corporation for over five years.

“We have to cut off electricity to houses where they don’t pay the bill. Cutting was the busiest in July,” he explained. “That happened in almost every township in Yangon.”

Residents from various townships in Yangon – including Lanmadaw, Latha, Sanchaung, Bahan and others – confirmed to Frontier that YESC officials cut off their electricity in July. May Oo’s neighbourhood appears to have been one of the last to go.

Like May Oo, Sanchaung resident Ko Win Aung relented after losing power in July.

“There were many people like me who went to pay the bill because they were cut off,” he said. “All of the residents from my ward paid. We can’t live in the dark.”

The Independent Economists of Myanmar (IEM) claimed in July last year that the regime was losing about 100 billion kyat per month due to the public boycott. Although based on Frontier’s recent interviews in Yangon, this income has likely surged significantly recently, especially because people are being forced to pay back their cumulative debts.

By now, Tun Zaw said there are “very few” people refusing to pay their electricity bills in Yangon.

“I don’t even keep the bill”

But elsewhere, the regime has still been unable to roll out its administration in the face of fierce armed resistance. Frontier found that Dry Zone residents of Sagaing and Magway regions, strongholds of the anti-coup People’s Defence Forces, continue to refuse to pay in large numbers.

In Sagaing’s Ayadaw Township, resistance to the military remains strong, as PDFs wage guerrilla warfare on regime forces. In these remote areas, some villages only began receiving public electricity in 2020.

“About six months before the military coup, our village got electricity,” said Daw Aye Mi. “After the coup, there was a strike, and no one paid their electricity bill. No one dares to come to collect them because there is fighting in our area.”

In Kalay Township, which holds one of the region’s largest towns, residents say the boycott has split down the urban-rural divide. “Residents from the urban area pay their bills, but on the rural side they don’t pay because the military can’t control the countryside,” said one resident of Kalay town.

But in Sagaing town, many remain defiant even in the urban areas.

“Staff from the electric department send bills to our homes monthly. But we don’t pay,” said resident Daw Khin Thein*. “I didn’t even keep the bill; we don’t know where they are now.”

The story is much the same in neighbouring Magway Region, also a hotbed of resistance.

“They are not even cutting electricity in the urban area, and we’re not sure why,” said Aung Soe*, a resident of Magway’s Yenangyaung Township who has refused to pay since the coup.

Tun Zaw, the YESC employee in Yangon, said he understands his colleagues in certain parts of Sagaing and Magway “don’t dare collect bills” for fear of the ongoing conflict or being targeted for assassination.

“No one can guarantee your life if you go to pick up a bill,” he said.

Residents of the Dry Zone say they feel further justified in not paying because the regime is struggling to maintain consistent electricity supply, although this is in part caused by the mass boycott and resistance attacks on power infrastructure.

“Every day there is a power outage,” said Aye Mi in Ayadaw Township, adding the blackouts usually last around two hours.

According to the US Chamber of Commerce, power generation declined from 3,711 MW in October last year to 2,665 MW in March of this year. This decline is likely based on a combination of attacks on infrastructure, attacks on electricity staff, public boycotts and general junta incompetence.

The junta’s electricity ministry did not respond to requests for comment, but the regime previously attributed the electricity shortage to resistance attacks and a rise in gas prices affecting LNG projects.

Piling on pressure

Resistance groups have targeted many branches of the junta’s administration, from police stations to local administration offices, and somewhat more controversially, electricity offices.

“The military puts pressure on the people and to pay their electricity bills. Revolutionary forces pressure people to prevent them from paying,” explained the student activist, Min Kyaw.

While such attacks may have been initially effective in discouraging payments to the regime, and appear to still be effective in Magway and Sagaing, they are controversial for putting civil servants and ordinary civilians at risk. In July last year, Khit Thit reported that two people were killed in a bomb attack on an electricity office in Mandalay – one public worker and one woman who was paying her bill.

“When I come to the office, I feel unsafe,” said Tun Zaw, the YESC worker.

Like many others, Tun Zaw joined the mass anti-coup protests but did not join the mass strike of civil servants, as he felt compelled to continue working in order to support his family.

“My life was like an ocean of trouble. I had no choice,” he said.

Less controversial, have been attacks on infrastructure, which don’t bring the same level of risk to civilians. On the border of Kayah and Shan states, PDFs and the Karenni Nationalities Defence Force destroyed two electric towers connected to the Lawpita Hydroelectric Plant No. 3 in August last year.

“Yes, we destroyed the tower at that time,” an official from the PDF Pekon confirmed to Frontier. The power plant supplies electricity to major cities, and Pekon PDF claimed at the time that the tower that was attacked was connected to the heavily militarised capital of Nay Pyi Taw.

“This power line is mainly used by the military. We attacked it to stop their administration,” a KNDF spokesperson told Frontier.

While attacks on infrastructure and electricity offices appear to have declined since last year, the KNDF spokesperson said the group again attacked a Lawpita electricity tower near Moebye town just on November 3, as a battle rages for control of the city.

“Electricity is a main requirement for the SAC to run their administration,” he said, refusing to comment on whether there have been fewer attacks this year, or whether the KNDF would step up attacks in the future.

“They need electricity to produce weapons and communicate in support of their military strategy.”

Khin Thein, in Sagaing town, said she will persist with her boycott until the military is no longer in power.

“Even if the regime doesn’t fall, by not paying the electricity bill, we show our defiance,” she said. “If our Mother Suu’s government returns to power, we will pay it immediately,” she added