As Facebook cracks down on disinformation in Myanmar, observers warn that some bad actors are moving to YouTube, where lax enforcement is allowing fake news and content theft to proliferate.

By BANYAR KYAW and PHONE HTET NAUNG | FRONTIER

In 2020, Facebook won rare praise from social media monitors for its efforts to minimise disinformation on its platform before, during, and after Myanmar’s 2020 election. It added more staff focused specifically on Myanmar content, introduced artificial intelligence to proactively remove hate speech, and worked closely with civil society.

Other social media platforms received less-glowing reviews for their response to the disinformation threat – particularly YouTube, the video-sharing platform owned by Google.

“We’re seeing bad actor[s] increasingly move to YouTube as a hosting platform. YouTube has been far too slow to respond to ongoing emergencies,” Ko Myat Thu from the Myanmar Tech Accountability Network said in a statement on November 7, a day before the election.

YouTube’s lack of responsiveness was illustrated that very night. At around midnight on election eve, more than 30 Facebook accounts near-simultaneously posted videos from YouTube that claimed foreigners, including billionaire philanthropist George Soros, were influencing the election.

Most of that first wave of disinformation was quickly taken down by Facebook, Myat Thu said, but YouTube took significantly longer to remove the videos and the account, MMLeakTeam, that had posted them.

More than two months on from the election, disinformation continues to spread on the platform. Some content seems intended to undermine the credibility of the election, while other videos contain conspiracies about COVID-19.

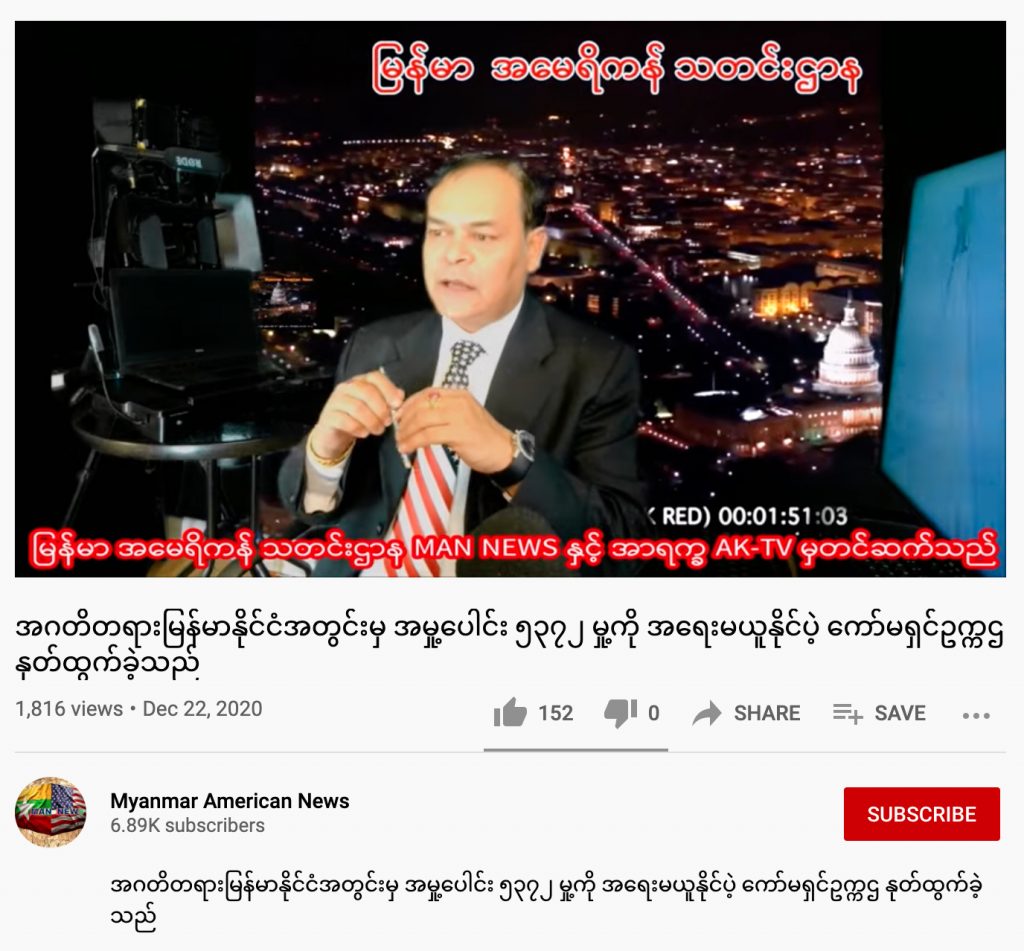

The channel Myanmar American News, with more than 7,000 subscribers, has been one of the main sources of disinformation on YouTube since the election. It primarily spreads baseless conspiracies about election irregularities, some of which then make their way to Facebook.

The channel is run by a person who uses the name “Goshal Lay”, who told Frontier he is a resident of the United States. A frequent guest on the channel is “Andrew Soe”, who also has his own YouTube channel with more than 9,000 subscribers.

Two platforms, two approaches

The Myanmar American News and Andrew Soe channels highlight how Facebook and YouTube are taking vastly different approaches to disinformation on their platforms.

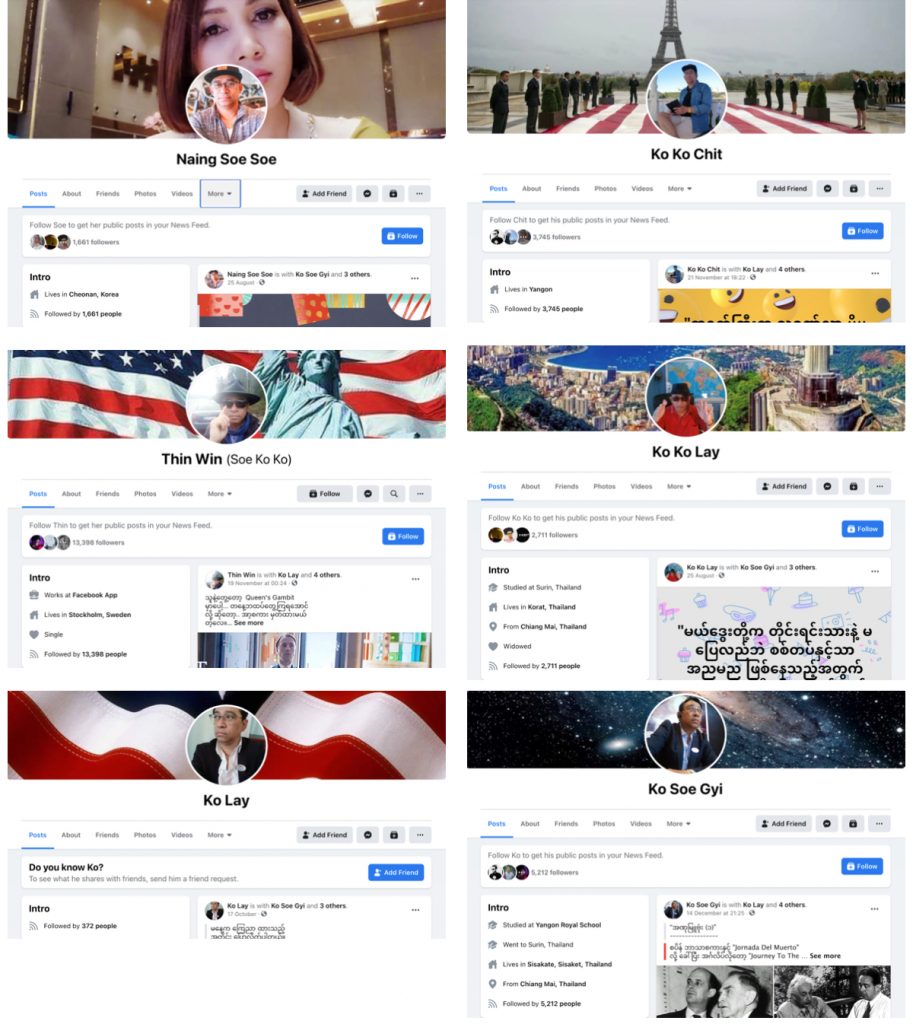

When Frontier first began its investigation, it found that Andrew Soe also appeared to be running multiple Facebook accounts under pseudonyms – a violation of Facebook’s rules, which require accounts to be in the user’s real name. Andrew Soe’s two most popular Facebook accounts, which went by the names Thin Win and Ko Soe Gyi, had nearly 19,000 followers between them. All the accounts used his photo as their profile pictures, and were frequently used to share his YouTube videos, along with other original disinformation posts.

After Frontier reported the accounts to Facebook, they were all removed or locked under Facebook’s “authentic identity policy”, under which Facebook commits to removing accounts that misrepresent users’ identities. YouTube, on the other hand, took much narrower action, as detailed below.

In one video, first posted by Myanmar American News, Andrew Soe claimed that 40,000 fraudulent ballot papers signed by polling station officers and stamped by the ruling National League for Democracy had been found, without providing further details. It also said NLD members had been caught with 144 ballot boxes in Payagyi, Bago Region – a claim that has not been corroborated by any legitimate news sources. This video was then shared on Facebook by one of the accounts that appears linked to Andrew Soe, called Thin Win, earning a fact-check warning from Facebook but still garnering over 460 shares.

Thin Win, which has 13,400 followers, tagged five other accounts in the video, all of which have been frequent distributors of disinformation linked to Andrew Soe. But Thin Win has also occasionally posted original content that qualifies as disinformation, such as the debunked but persistent claim that 39 million people voted out of 37 million eligible voters. The post has received nearly 500 reactions and 140 shares. A post from the account that claimed the NLD “stole advance votes with enormous bags” – an allegation of ballot-stuffing made without seemingly any evidence – had over 500 reactions. In both posts, Thin Win again tagged either all or some of the other accounts that appeared linked to Andrew Soe.

Those other accounts, like Ko Soe Gyi, which had 5,500 followers, also spread their own disinformation. Although their main focus was on election activities in November, some of the content began to shift to other topics, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, once the vote was completed. In a December 10 post that he attributed to Andrew Soe, Ko Soe Gyi wrote that vaccines will cost K2.5 million to K5 million (US$1,875 to $3,750) and the profits from their sale would be used to “reimburse the [NLD]’s election expenses”. The post had been shared more than 260 times before it was removed.

The same day, Ko Soe Gyi also posted a video from Myanmar American News that alleged the NLD had essentially engaged in vote buying, by borrowing money from the international community for its COVID-19 response and then using it to pay people K40,000 in exchange for their vote. While the post has been removed from Facebook, the videoremains available on YouTube. Like Thin Win, Ko Soe Gyi also tagged the other five accounts in many of posts. Andrew Soe did not respond to requests for comment.

The disillusioned activist

Myanmar American News host Goshal Lay – real name U Aung Naing Htwe – is another prominent spreader of disinformation on YouTube.

In one video, Goshal Lay falsely claimed that President Win Myint is Chinese but was “transformed into a naturally born citizen”. He also claimed, without evidence, that the president is “committing corruption” which he promised to reveal “in the future”. He also launched a sexist attack on State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, saying she was previously a “maid and a wife” who is “mismanaging” the government. In yet another video, he claimed that “boxes of votes were imported into the polling station,” supporting baseless allegations of widespread voter fraud. He called it a “very beautiful trick” and said it was perpetrated in Pathein Township in Ayeyarwady Region, Hlegu Township in Yangon Region and Paung Township in Mon State. He also alleged the NLD had benefited from “thousands” of falsely stamped and therefore fraudulent ballots.

In an interview with Frontier, Goshal Lay stood by most of his claims of voter fraud. He suggested that the UEC should “search people’s bodies” when they come to polling stations, as people may “change the votes in the back”.

But Goshal Lay also subscribed to conspiracy theories about voter fraud in the US presidential election, particularly regarding early voting, that have been spread widely by President Donald Trump, culminating in an angry mob storming the Capitol building in an attempt to reverse the election results. Goshal Lay said early voters in the US changed their registration “so that they can vote [again] in other states”, a claim not backed up by any evidence.

Despite his recent habit of spreading information that targets the ruling NLD, Goshal Lay claimed to be a former member of the 88 Generation group, which led the pro-democracy uprisings in 1988. He’s not the first disinformation peddler to claim this link; Aung Min of Myanmar Hard Talk, a page that spread anti-Rohingya and anti-NLD conspiracy theories, also told Frontier he was forced to flee Myanmar due to his pro-democracy activism.

Goshal Lay said he was imprisoned for writing an article about democracy and experienced repeated harassment. “If there is any political problem in the country, military intelligence came and interrogated me,” he said. He claimed he started a news outlet from Bangkok called the Rangoon Post and worked for another international news outlet that he refused to name. While the Rangoon Post did exist, neither the name Goshal Lay or Aung Naing Htwe appear on the masthead of past editions as seen in Burma Library.

Goshal Lay said he was “happy” when Aung San Suu Kyi came to power and saw her as an “icon of democracy” but became disillusioned almost immediately, when she announced her cabinet back in March 2016. Many were not qualified, he said. “For example, they appointed a math teacher as agriculture minister.”

He claims his new line towards the NLD is because they are now in power and must be held accountable, but he also admits there are “personal problems”. In one of the more bizarre moments of the interview, he claimed that somebody used vulgar language towards him in a Facebook post, and claimed that he knew the post originated from inside Aung San Suu Kyi’s home, but did not come from the state counsellor herself.

A refuge for scammers and hatemongers

But Andrew Soe and Goshal Lay are just the tip of the disinformation iceberg on YouTube.

The platform also hosts anti-Rohingya activist Mr Rick Heizman. Since being banned from Twitter and Facebook, he has turned to YouTube to share disinformation and conspiracy theories. Many of Heizman’s videos are purportedly taken from inside training camps for the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, although he offers little evidence to corroborate this. Some are explicitly disinformation, like this video in which he edited an Aung San Suu Kyi speech onto a television that a man then punches. Others appear to be deliberately misleading, like two videos showing “How to create fake victims”, where a group of men create staged death scenes. While Heizman doesn’t identify where the videos purportedly took place, the men are wearing Iraqi police uniforms, but have been used by his followers as evidence that Rohingya faked the crimes committed against them.

There also appears to be a thriving content stealing industry on YouTube, with multiple channels dedicated to reading out news articles published by legitimate media outlets, which are not credited for their work. The scheme is likely an attempt to gain clicks and money, as the thumbnails and titles are often inflammatory, sexualised or misleading. As Frontierreported in October, Facebook has already taken action against similar scams being perpetrated on its platform.

In one example from YouTube, this video from Top Burmese Channel simply features a narrator reading an article by The Irrawaddy speculating about who the next cabinet members will be. The video has nearly 360,000 views but does not identify the original publication. Another video by the same channel falsely advertises itself as a debate between Union Solidarity and Development Party chair U Than Htay and Aung San Suu Kyi, but is actually just a speech by Tatmadaw chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. The original thumbnail, which has since been changed, falsely claimed that Than Htay had resigned as chairman of the USDP. The video has over 22,000 views. Other videos have sexually provocative thumbnails, but offer unrelated content.

Some of these channels seem to be related to Opera Mini and Opera Entertainment, which have already been deleted from YouTube. The channels persistently shared anti-Rohingya, anti-NLD content, but like Top Burmese Channel seemed more motivated by garnering clicks and money. Opera Mini once posted a video narrating a story from The Irrawaddy saying the Restoration Council of Shan State is open to holding elections in Mongkaing Township. The video gained over 17,000 views before Opera Mini was taken down.

Later, similar videos narrating the same article soon appeared on other channels. On one of these channels, Step Media Group, it has received another 6,000 views. Unlike Opera Mini, these new channels seem to avoid posting outright disinformation or hate speech content, perhaps in an attempt to avoid removal.

After Frontier reported videos from Myanmar American News, Andrew Soe, Rick Heizman and Top Burmese Channel, YouTube took only limited action. One video from Andrew Soe’s channel was removed for hate speech, while one was removed from Rick Heizman’s channel for harassment violations. On other videos YouTube put in place age restrictions. The only channel to be removed entirely was Top Burmese Channel, for violating spam and scam policies.

YouTube told Frontier it removes content that is deceptive, including technically manipulated videos that may mislead viewers. But even after Frontier reported Rick Heizman’s blatantly manipulated video to YouTube, it failed to take action and the video remains accessible. The company also said it has strict policies against hate speech and was increasingly taking action; compared to early 2019, it is now removing 46 times more hate speech per day globally.

However, with disinformation actors and scammers increasingly being banned from Facebook, some argue that YouTube needs to be more proactive in removing content. Myat Thu, from MTAN, told Frontier that “prominent Facebook propagandists” are moving to YouTube as their pages are banned on Facebook. While he said the problem isn’t particularly serious yet, he cautioned that YouTube’s popularity is increasing in Myanmar and it would need to be vigilant to avoid the problems Facebook has faced.

“It is impossible that YouTube has not noticed what’s happening in Myanmar,” he said. “They may be pretending not to know. Reforms should be made right now.”