Separate investigations have identified networks of social media pages that are driving users to third-party websites to generate ad revenue, in what Facebook has described as “inauthentic” behaviour that violates its policies.

By ANDREW NACHEMSON and BANYAR KYAW | FRONTIER

Facebook has removed more than 650 pages and accounts from multiple “separate spam networks” in Myanmar that it says violated policies by driving users to third-party websites with the goal of generating ad revenue. A separate, unrelated investigation by Frontier found three more accounts engaged in very similar behaviour, including one with more than 5.3 million followers.

Facebook said the networks it uncovered were examples of “inauthentic behavior”, which it defines as being primarily focused on profit. This differs from the better-known “coordinated inauthentic behavior”, which is usually politically motivated.

“The vast majority of [inauthentic behaviour] across all of social media that we see are spam or scams designed to get virality in order to monetise, in order to get money,” Mr Nathaniel Gleicher, head of Facebook’s security policy, told Frontier.

He said the pages mostly focused on celebrity news and current events. While they sometimes did engage in politics, Facebook saw no evidence that they were primarily politically motivated. Rather, Gleicher said these forays into politics were “clickbait tourism” designed to take advantage of what was popular in order to achieve the primary goal of profiting from ad revenue.

The networks were also investigated by independent network analysis firm Graphika, which agreed that the content was primarily tabloid in tone.

“Sometimes in the mix, you’d get other kinds of clickbaity content, some of which is questionable, some verging towards health misinformation,” said Graphika’s director of investigations Mr Ben Nimmo, who added that the spread of political-themed content and misinformation on the pages was “not systematic”.

Nimmo said some pages practised “borderline impersonation”. For example, one page implied an association with a Myanmar pop star, using his photographs and “leveraging his brand” to gain more followers and drive more traffic. “A lot of this is about audience building: you try to make yourself look credible or popular by associating yourself with somebody already credible or popular,” he said.

Among the removed pages, Nimmo said the largest had around five million followers, while “a bunch” of others had over one million.

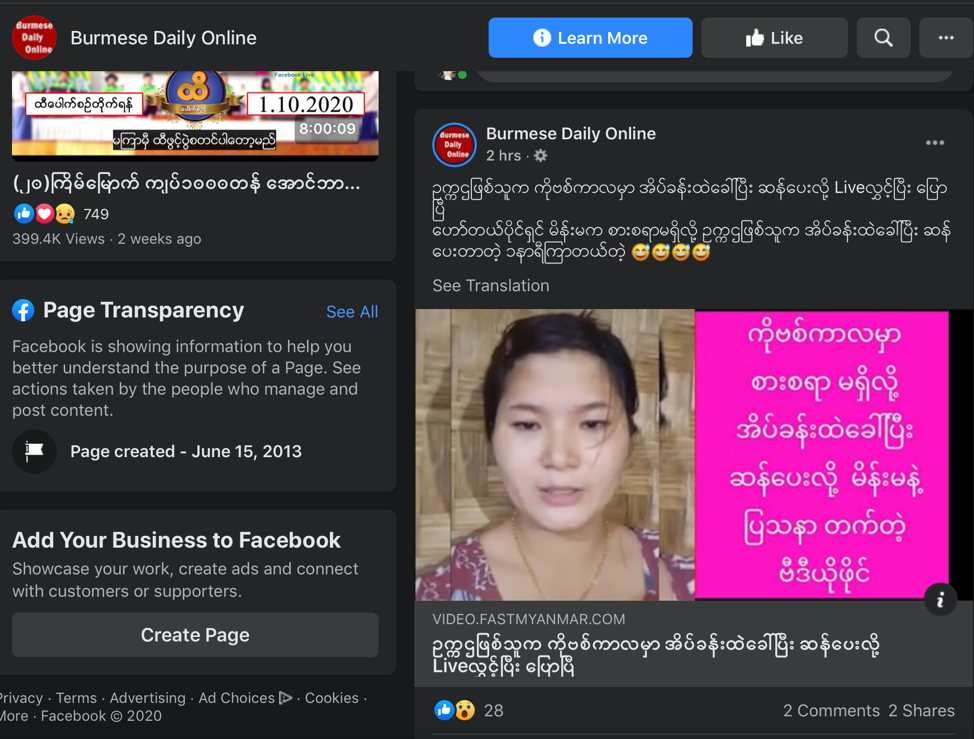

Separate from Facebook’s investigation, Frontier has been examining pages that seem to fit the same pattern of behaviour. The Burmese Daily Online page, for example, also directs users to four ad-heavy clickbait sites. The websites, while using different URLs, often post the exact same clickbait news stories, a tactic Nimmo said is sometimes used to avoid spam filters. Burmese Daily Online’s Facebook page has over 5.3 million followers and has changed its name six times since beginning as “BrainWave” in 2013.

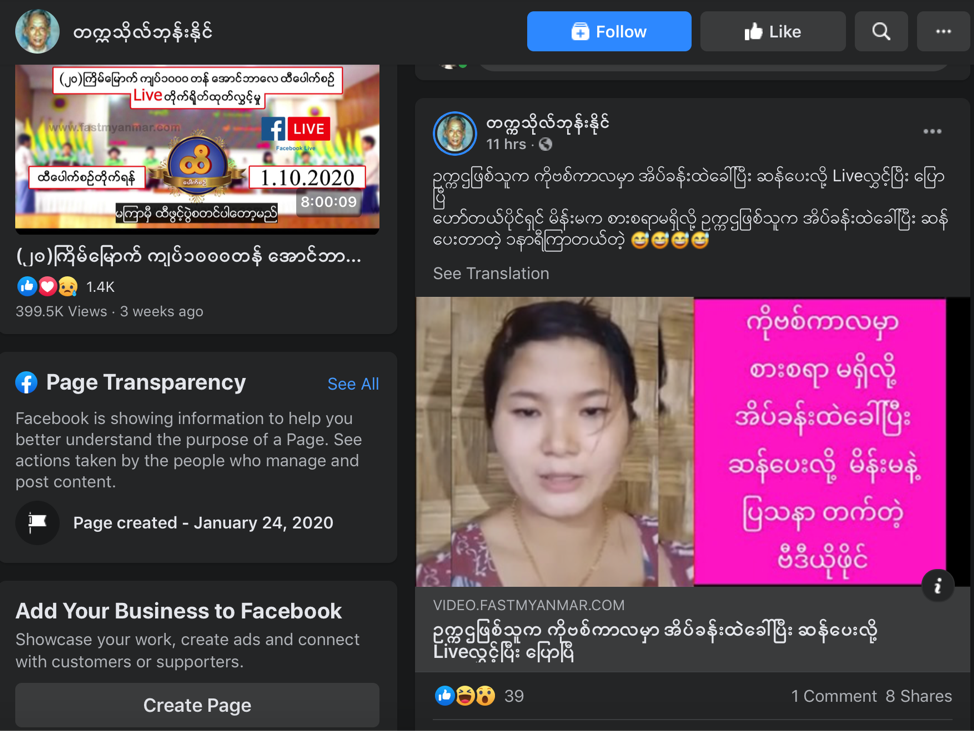

Frontier has found other pages directing users to the same websites that Burmese Daily Online links to, including this page with over 140,000 followers. This suggests that they may be part of the same network. This second page uses the name and image of the famous late writer Tekkatho Phone Naing, seemingly in an attempt to build off his popularity, just as the network Facebook uncovered did with the pop star.

A third account, “Nwe Nwe”, seems to share the content to public groups, posting dozens of links from those four websites in a group with more than 2 million followers, and another group with over 180,000 followers, among others. Sometimes Nwe Nwe would post the same link in different groups less than a minute apart.

Frontier reported this cluster of three accounts to Facebook.

Gleicher said while inauthentic behaviour poses separate challenges to the politically focused coordinated inauthentic behavior, Facebook hopes to introduce new measures to make such money-making strategies less appealing.

“If you have a nation state doing this, you need to put controls in place [that are necessary] to prevent them, but you need to recognise they are going to keep investing and keep trying,” he said. “For a group like this you know that their goal is to make money in most cases which means that over time we can make this more and more costly, we can make them less and less effective, and we can deter them.”