The Myanmar Hard Talk Facebook page took advantage of the grey area between outright disinformation and legitimate political commentary to spread a nationalist, pro-military agenda.

By PHONE HTET NAUNG, BANYAR KYAW, ALEX BEATSON and ANDREW NACHEMSON | FRONTIER

Combatting online disinformation and misinformation requires navigating a complex environment flush with everything from political commentary and controversial views to outright falsehoods and hate speech, and debate continues over where to draw the line between opinion and disinformation. Some take advantage of this ambiguity, intentionally spreading disinformation and hate speech while defending it as opinion.

Enter Myanmar Hard Talk, an unabashedly nationalist, pro-military Facebook page with close ties to a controversial lawmaker from the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party. The page’s creator sought to portray his project as political commentary, but Frontier found that it was frequently posting outright disinformation including content that could inflame racial or religious tensions, and that it associated with known extremists.

Facebook had taken action against multiple isolated pieces of content for violating rules after they were reported by Frontier, but the page remained online until some time today, Friday, October 23. Facebook says it has removed the entire page for repeatedly violating its community standards.

In one of its most egregious examples of spreading disinformation, MHT published a provocative video that it claimed contained footage found on a computer belonging to the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army. In 2016 and 2017, ARSA attacked Myanmar police outposts, prompting a Tatmadaw campaign against the Rohingya that some have described as a genocide. The MHT video claimed ARSA is a threat to Myanmar’s sovereignty and the group was training to invade Rakhine State.

Frontier found that much of the footage was drawn from videos first posted by Mr Rick Heizman, an openly anti-Muslim campaigner who has claimed that Rakhine State is the target of a global Muslim conspiracy to destroy Buddhism, and once called for 800,000 Rohingya to be expelled to Bangladesh. The contents of the original Heizman videos could not be verified, and there was no explanation for how he obtained the footage. It had over 100,000 views and 7,000 shares when Frontier reported it to Facebook, which then removed the post.

Facebook removed the video under its Myanmar-specific election period misinformation policy, finding that the content has the potential to either suppress the vote or damage the integrity of the election. The company has special policies that apply only in Myanmar and reflect the country’s volatile history, allowing it to remove misinformation or “unverifiable rumors” even if they don’t specifically violate voter interference policies.

Facebook said Heizman was originally banned for various policy violations in 2018 and has been banned multiple times since then while trying to rejoin the platform. He has now moved on to YouTube, where Frontier found he had posted multiple examples of blatant disinformation, including a doctored video.

In another example, MHT spread a false rumour that a poem written by State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi had been plagiarised from a Russian poet, Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky. Despite multiple fact-checkers debunking the story and Frontier reporting the post to Facebook, it remained accessible on the social media platform until the entire page was removed. Despite being disinformation aimed at discrediting the leader of the country’s leading political party, Facebook said the post wasn’t specifically election-related and didn’t meet criteria for removal.

In another MHT post, the outlet claimed, without evidence, that “there are a lot of drug dealers and gang members in the NLD campaign”. It added, again without evidence, that “most of the drug dealers are wearing local NLD party uniforms”. The post was taken down prior to the page’s removal.

In addition to posting video clips and text, the page also frequently hosted talk shows, featuring a USDP MP, Tatmadaw supporters and hardline nationalists.

MHT launched on November 18, 2019 – the same day that the International Court of Justice announced that it would hold public hearings on The Gambia’s accusation that Myanmar committed genocide against the Rohingya. That same day, MHT published a post criticising the ICJ case, calling it an accusation against all citizens, which has become a common rallying cry as the case has progressed.

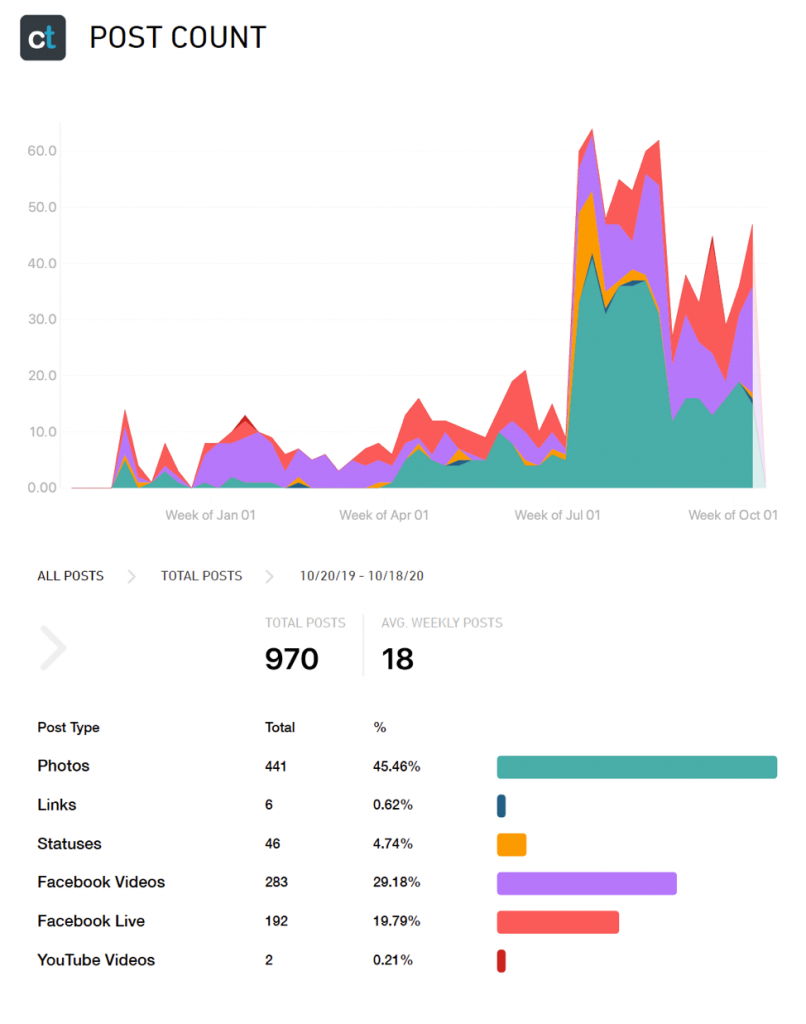

For a while, MHT existed on the fringes of Facebook, accumulating only a moderate following. It appeared to be connected to several other pages that are no longer active and have fewer followers: MOV News and Myanmar open voice – mov both use similar logos, or email addresses, and the same defunct website link. But MHT saw huge growth in recent months, accelerating as the election approaches. It had over 240,000 followers and more than 150,000 likes when it was taken down. The other pages remain online.

Behind the page is a man named U Aung Min. An enigmatic political commentator, he told Frontier he models his talk show on the “black man show” in America – possibly a reference to “The Daily Show with Trevor Noah”. He has claimed to be a Dutch citizen who fled Myanmar after participating in the 1988 protests against the military government. He said he started MHT to “resist” coverage in other media outlets, and runs the page on a shoestring while living with his mother.

The Dutch embassy said it was unable to confirm his identity due to privacy restraints.

Despite claiming to have participated in a protest movement that was ruthlessly suppressed by the military regime, Aung Min’s content is almost universally pro-military and anti-NLD. “Young people in Burma do not understand the role of the military… they do not understand how the military built the nation,” he told Frontier, adding that “senior military leaders pushed Burma on the path to democracy”.

One of Aung Min’s most frequent guests is U Maung Myint, a USDP central executive committee member who represents Sagaing Region’s Mingin Township in the Pyithu Hluttaw, the lower house of Myanmar’s national legislature. Maung Myint is also a retired military officer who once served as deputy minister for foreign affairs under the military junta, then as social welfare minister and later minister for industry in U Thein Sein’s USDP government. He has a close relationship with some of Myanmar’s most infamous nationalists.

Earlier this year, Maung Myint attracted attention when he revealed on Myanmar Open Talk, one of MHT’s affiliated pages, that he purchased an apartment for a group of extreme nationalists to use as an office headquarters. “Our party is a nationalist party,” he said at the time. The group included nationalist hardliner Daw Khin Waing Kyi, who has close ties to now disbanded Buddhist extremist group Ma Ba Tha, which encouraged racial violence against the Rohingya. Khin Waing Kyi, while a lawmaker for the National Democratic Force, also first proposed the controversial “race and religion laws”, which critics say codified discrimination against non-Buddhists, especially Muslims, by regulating religious conversion and inter-religious marriages.

Asked about his relationship with Aung Min and MHT, Maung Myint said, “We only know each other through online live discussion.” He said Aung Min “caught my eye” and admitted that his interviews with MHT helped boost Aung Min’s reputation. Maung Myint refused to answer a question about MHT using his image to promote the page, claiming he was too “busy” with election campaigning. He also denied contributing any funds to MHT.

Asked if he believes MHT was spreading disinformation, he said, “I don’t want to talk to you anymore.”

During his appearances, Maung Myint and Aung Min often attacked the NLD while defending the USDP and military. Most of Maung Myint’s comments can’t be described as outright disinformation, but rather slanted opinions that don’t hold up to much scrutiny. For example, in one recent video, Maung Myint said the international community forgave Myanmar’s debt under the USDP, but then made the NLD repay it, claiming this is proof that the USDP has more support in the international community. The statement is factually incorrect in several ways: while the international community forgave some debt under the USDP, it also issued new loans to Thein Sein’s government that Myanmar will have to repay. Most political analysts would likely disagree that the international community supports the USDP more than the NLD, but this could be chalked up to a matter of opinion.

While Maung Myint appeared to be careful to toe the line in his interviews with MHT, on the campaign trail he has been known to peddle Islamophobia and disinformation. During a speech recorded and published to Facebook on October 11, he claimed the NLD has selected 42 Muslim candidates to run in the November election, and said that as a result people shouldn’t vote for the party. However, only two NLD candidates have been confirmed to be Muslim. Maung Myint referenced one of them by name, U Sithu Maung, calling him a “Muslim kalar”, a term widely considered to be derogatory.

In a Facebook post in July, Maung Myint also shared unverified images and texts apparently insulting Buddhism, using them to argue that the NLD government had failed to protect Buddhism and urging people to vote for the USDP. The images included a photoshopped foot covering Buddha’s face and a caption riddled with insults against Buddhism.

In another video that MHT posted, hardline nationalist U Win Maw criticised the NLD for “suppressing our religion and monks”. “Therefore, we keep questioning, what does the government want and who is behind them? And who are they making deals with outside the country to cancel the religion of our country?” he asked.

Again, this seems to be a reference to a fictional global movement to destroy Buddhism in Myanmar – a discredited conspiracy theory used to justify the crackdown on Rohingya Muslims. In fact, the overwhelming majority of those in power in Myanmar remain Buddhists.

When asked if it was appropriate for a USDP MP and candidate to appear on a Facebook page like MHT, party spokesperson Daw Nan Mya Mya Mie Mie Zaw defended MHT and Maung Myint. “It is up to the individual to decide whether MHT is unethical,” she said, and dismissed accusations of disinformation as simply a difference of opinion.

She said there are “some official media pages that have a blue checkmark on Facebook that continue to campaign for a party”, but refused to name the pages or the party she was referring to. She also did not disclose if those pages had shared disinformation.

But Nan Mya Mya Mie Mie Zaw appears to have her own history of posting religiously inflammatory content on Facebook. In September, she wrote that “Buddhism has been insulted under the government of the Nobel Peace Prize laureate,” a reference to Aung San Suu Kyi. She also said “one of the world’s largest religions is insulting our country and sovereignty”, a likely reference to Islam. Members of the Myanmar Press Council took a different view. U Zayar Hlaing, secretary of the MPC’s media ethics committee, said MHT is “unethical”. “It must be declared that it incites hatred. This is very simple,” he said. U Myint Kyaw, another MPC member, said MHT will be formally designated as an outlet spreading disinformation in the near future.