Edwin Vanderbruggen has spent the last five years in Myanmar as legal advisor to some of the biggest players in the oil and gas, energy and telecoms sectors. A partner in the VDB Loi network of law firms, he helped to facilitate the ground-breaking joint-venture agreement in September between Myanma Petroleum Products Enterprise and Singapore-based multinational Puma Energy, for jet fuel distribution. Mr Vanderbruggen spoke with Frontier about the challenges of privatisation in Myanmar and how government officials are learning to do business in the global market.

The joint venture between MPPE and Puma caused a stir. Is that type of deal rare?

It is. It’s not the first privatisation, but it is the first privatisation with a foreign investor…There have been joint ventures before, but not in the framework of privatisation. That’s a first, and it’s a miracle we got it through (laughs).

A miracle?

It is. There are a lot of unprecedented things that we have to resolve for the first time ever. Getting an agreement on the main commercial points and the legal points, securing approvals from the cabinet, from the Attorney General, all of these things, that’s all new.

We wanted to make sure that the documentation was of an international standard as much as we could make it.

Was the deal attractive to bidders in the end?

We ended up doing the advanced stage with three competitors, and they were three strong competitors and all three were quite eager to do this contract with us. And we went through several series of, frankly, playing them out against each other to try and get even better conditions.

So both the government and investor needs to feel comfortable, but [the investor] particularly because the government is the majority…The bidder wants to do the deal. That’s why he’s here. But not at any price. They know this is Myanmar, so they expect a certain degree of risk. To a certain degree you will be able to accept that, but only to a certain degree, so we have to work with the foreign investor to say, “Is there anything we can do to alleviate your concerns?”

Does it indicate a trend towards privatisation?

It’s really difficult to draw general conclusions because it really depends on the ministry, but definitely on the whole you can see what they’ve been trying to do. You open the state budget law and you see that most of the state-owned enterprises, they make losses. And they have been making those losses for many years.

In 2011, 2012, from what I understand the minister of finance started to quietly say to a number of ministries, “You know what, next year you’re on your own. You do what you want, but there’s no more money from us. So you better fix it.”

How can they “fix it?”

I think one of the main challenges is that many of the state-owned enterprises were having difficulties because the management was not sure how to run it as efficiently as a business. But if you want to do a privatisation successfully you need exactly the same skills, because a privatisation means you need a business case.

So if you need to be privatised it’s because you’re not running a good business, but in order to privatise you need to have business skills. Isn’t that a Catch 22?

It is. That’s absolutely correct. And that’s why not all privatisations have been a success. Many of them, they don’t proceed…How many tenders have you seen about joint ventures with the government? Dozens, right? So how many announcements have you seen about joint ventures being successfully concluded? One. That’s this one [with Puma].

That’s why I said it’s a miracle we got it through. Because it is really that hard. Already you start from a difficult position because if it was making loads and loads of money, nobody would privatise it. You see them selling shares in MPT? No, they don’t. Why do I have to give you equity? I’m making good money now.

And then on top of that, government officials everywhere in the world, they are not geared how to figure out how to make the best of what they have. Businesspeople, they are good at that, because business people have to make a profit. They are all geared toward efficiency…What we need to do in Myanmar, we need more of that efficiency.

How do you see that efficiency playing out with the MPPE-Puma joint venture?

The jet fuel deal, it’s all about infrastructure. According to the McKinsey report, [Myanmar] needs $230 billon in investment in infrastructure, just to become competitive. That is staggering. In energy, transport, in real estate, in water, in sanitation, in waste, in health, in schools; it’s just mind-boggling.

We need efficiency of the private sector to help with that. Because the public sector has money, but the private sector has more money. Their investors, their lenders, they can make stuff happen. And with their efficiency, it’s like magic.

But it’s very hard here, because it’s very hard now for the government to try and put the business case together for any type of thing that they want to do. They have no experience in that, and that’s normal. It’s not their fault because they’re working really hard at it. And there have been some successes. Look at telecom, that went great. Now we have the banks; that goes well. So, OK, now what’s next?

What is next?

To get to those US$230 billion, we’re going to have to strengthen the way the government makes projects attractive to the private sector. That’s the problem. The government needs more help to understand what kind of stuff private sector will do, and what they won’t do.

Part of why this is so hard is because they are existing businesses. You’re continuing an existing business, and you’re making it bigger.

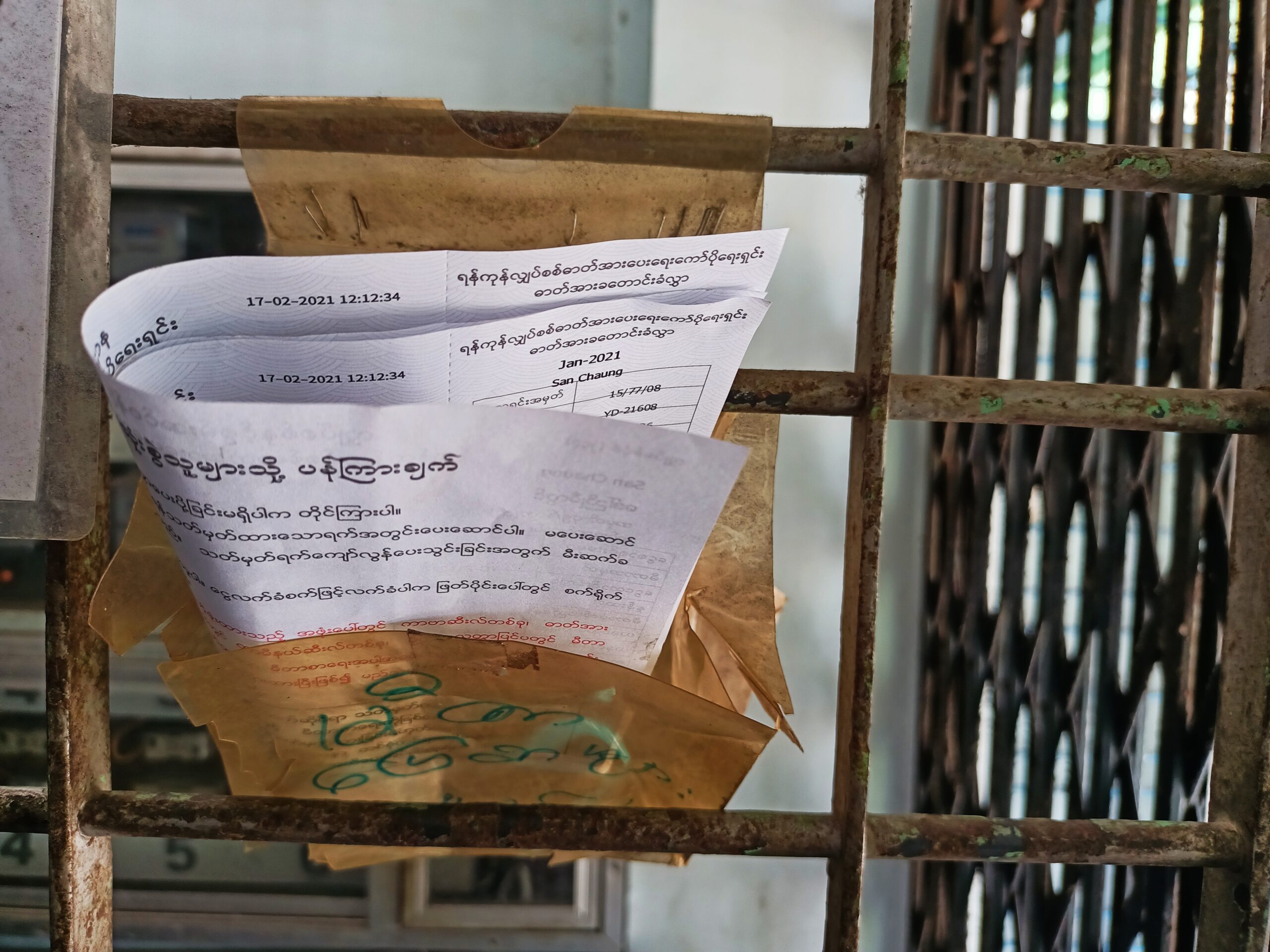

In general, government entities do a lot of work with other government entities. But in the past they often didn’t document those transactions well. Because it’s government anyway, right?

They do business with each other all the time. They do financing. They sell things to each other. They use each other’s land, they use each other’s staff. Lots of stuff. So then a lot of that, sometimes they didn’t keep proper records because, why bother? It all goes in the same pocket anyway. That’s no longer true now. Now you have shareholders, buddy. Now you have shareholders.

What does that mean for your team?

You have to go through everything, and you have to document everything properly and identify if there’s any issues in this. And often between government entities, they kind of leave things hanging.

The way we did [the jet fuel contract] was actually different from the way tenders are usually run. We did it competitively, objectively…You look at the way the Myanmar government did deals in the past, when they sell an asset or something, you’re talking about five pages. You know, they don’t really want to use complicated documents. But at an international level you have to.

When you talk about awarding tenders “objectively”, do you mean without things like under-the-table deals and nepotism?

I’m not saying that. I’m just saying we quantified it more. A good example for how not to do it is the first tender for Hanthawaddy Airport. Six or seven-page tender document. Lots of unanswered questions.

When then you do things properly, the bidders have much more confidence in you. We have these government officials. They’re working very hard, and they try to do the right thing, but they can’t communicate all the time with the business guys. Particularly the foreign business guys. They don’t understand each other, and it’s not about language. They don’t understand the expectations of foreign investors.

What sort of expectations do you mean?

Let’s say, out of the power sector. I build a power plant. You’re the government, you’re going to buy my electricity. Let’s say I need financing for this power plant. For me to get financing, I need you to confirm that in case our agreement falls apart, my bank can take over the plant. But originally, the government would say, “I don’t deal with your bank! This is going to be my plant, because this is BOT [build-operate-transfer], if you are unable to perform your contract, I will take the plant.”

That’s their position. Understandable. But if we keep that in the contract, there will be no plant because I cannot get the money.

But now they’ve evolved. MPPE, they understand that very well. The documents they are producing now all agree with that…They’re very smart. They just haven’t done this kind of thing before.

So you’re confident that officials can change their paradigm?

The mere fact that we did this deal and were able to get it through, I think it demonstrates, at least for the Ministry of Energy, that there is a vision here. Because a few years ago nobody would conceive this. This is what I admire about the minister for energy, because he has the political courage to do this, to tell his staff, “If we’re going to survive in this open market, we’re going to have to be as good as the other guys. And we can’t do that on our own.”