An average year in Myanmar typically incorporates a high number of holidays, and many of them are linked to the country’s strong relationship with religion.

By JARED DOWNING and KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

MOST MYANMAR people use two different calendars: The internationally-adopted Gregorian calendar, and the Kawza Thekkarit, a traditional calendar that still marks religious days, state holidays and astrological conditions.

Its first year (or epoch) is 638 C.E., around the same time it was introduced by King Popa Sawrahan as an update to the ancient Hindu calendar, and carried into the Ayeyarwady Valley by Indian astronomers.

While the Gregorian calendar is measured by the sun, the Myanmar calendar is lunisolar, going by both the sun and the moon.

Each new year begins in April, when the apparent position of the sun moves from Pisces (Mina) into Ares (Mesa).

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

But each month represents a moon cycle, beginning on the first day after the new moon. There are (usually) twelve:

typeof=

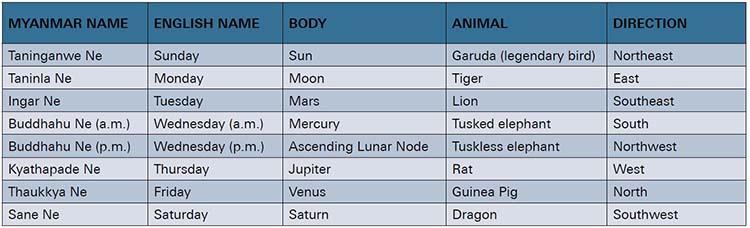

There are seven days in the Myanmar week, with each representing a cardinal direction, animal sign and celestial body. (The exception is Wednesday, which represents two of each.)

A day in the Myanmar calendar is called a yet, which is subdivided by factors of 60. One yet is into 60 nayi (24 minutes), one nayi is 60 bizana (24 seconds), and one bizana is 60 kaya (0.4 seconds).

Making the calendar work

The obvious trouble with a lunisolar calendar is that the movements of the sun and the moon never perfectly align. Thus, the Myanmar calendar must be continually adjusted.

A lunar year (354 days) is shorter than the solar year (and the moon’s orbit is somewhat irregular to begin with). Thus, the 12-month cycle is always falling behind at a rate of around 11 days per year.

The Karen New Year holiday typically takes place in December or January, around the time of New Year’s Eve in the Gregorian calendar. (AFP)

To catch the lunar calendar up to the solar, in certain years astronomers add a special intercalary month (like February 29 in a leap year) after the month of Waso (known commonly as Waso II) which brings that particular lunar year up from 354 days to 384 days.

The pattern by which intercalary months are added is complex and changes from time to time, but it always follows a cycle of 19 years (known in astronomy as the Metonic cycle) which is the time it takes for the new and full moons to return to corresponding solar days.

Of course, this is a highly simplified version of highly complex astronomical measurements, riddled with tiny irregularities and cycles within cycles within cycles.

typeof=

For example, the reason today’s Thingyan festival is three days long is because the traditional Myanmar year is actually 0.002387 days longer than the true solar year, which over the centuries has gradually pushed the first day of the year forward.

The time masters

The task of keeping the calendar up to date falls to U Aung Chit, 84, head of the three-member Calendar Advisory Board, under the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture.

From childhood, Aung Chit has been passionate about traditional astrology. He has spent more than 30 years on the advisory board, overseeing the complex calculations and practical considerations used to set the dates for official holidays and generally make sure the traditional calendar serves the needs of modern Myanmar.

“It is more proper to call ours a religious calendar,” he said, explaining that ordinary Myanmar people mostly use the calendar for astrological and religious purposes, marking days such as Yatyarzar, an auspicious day and Pyathada, a day of ill omen—a Myanmar version of Friday the 13th.

In some parts of Yangon, the Thadingyut full moon is celebrated with street festivals. (Victoria Milko | Frontier)

“Our calendar can be written only five years in advance, no more,” Aung Chit continued. “The Myanmar calendar is based on five types of cycles, the sun, the orbit of the moon, the phases of the moon, the seasons and the Buddhist calendar…That’s why we cannot write it hundreds of years in advance like Pope Gregory’s calendar.”

Since these various cycles are often completely independent, many of the decisions of the advisory board (such as the specific years in which extra months are added) are somewhat subjective, based on religious tradition and practical need in addition to actual astronomy.

“We make further calculations according to the Vinaya [code of conduct for monks] and the teachings of the Lord Buddha,” Aung Chit said. “After our board has discussed the year’s calendar length, we send the final draft to the Ministry of [Religious Affairs] and Culture, which approves it and publishes it as a gazette.”

The rest is history.