Some of the examinations set for monks who have devoted themselves to a life in robes are so arduous and stressful that they can affect a candidate’s mental and physical health.

By HEIN THAR | FRONTIER

Photos HKUN LAT

IN MYANMAR, becoming a Theravada Buddhist monk involves more than the ritual shaving of a man’s head before he undergoes an ordination ceremony and begins wearing robes and living in a monastery.

Many members of the sangha, as the community of monks is known, ordain for short periods but those who remain in the monkhood for an extended period are expected to sit the often gruelling examinations that test their knowledge of the Theravada Buddhist Canon.

The exams are set in Pali, the ancient ecclesiastical language of Theravada Buddhism, which is the predominant form of the religion in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia, as well as Myanmar.

Figures released by the Department of Religious Affairs in January show that there are more than 520,000 monks in Myanmar. The two main obligations of members of the sangha are study devoted to learning Buddha Dhamma, or the Buddha’s teachings, known as pariyatti, and the practise and practical application of Buddhist doctrine, called patipatti. Monks who do not apply themselves to pariyatti and patipatti are not as respected or revered by laity.

Support independent journalism in Myanmar. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The influence of the sangha, and of individual monks, is felt at every level among the Buddhist community, whether in a large city or small, remote village. The degree of influence that a monk has in a community depends on his sila (morality), samadhi (integrity) and panna (wisdom or insight). A monk’s achievements in pitaka exams also contributes to his reputation. Pitaka can be translated into English as “baskets” and the three baskets that comprise the Theravada Buddhist Canon are known as the Tipitaka.

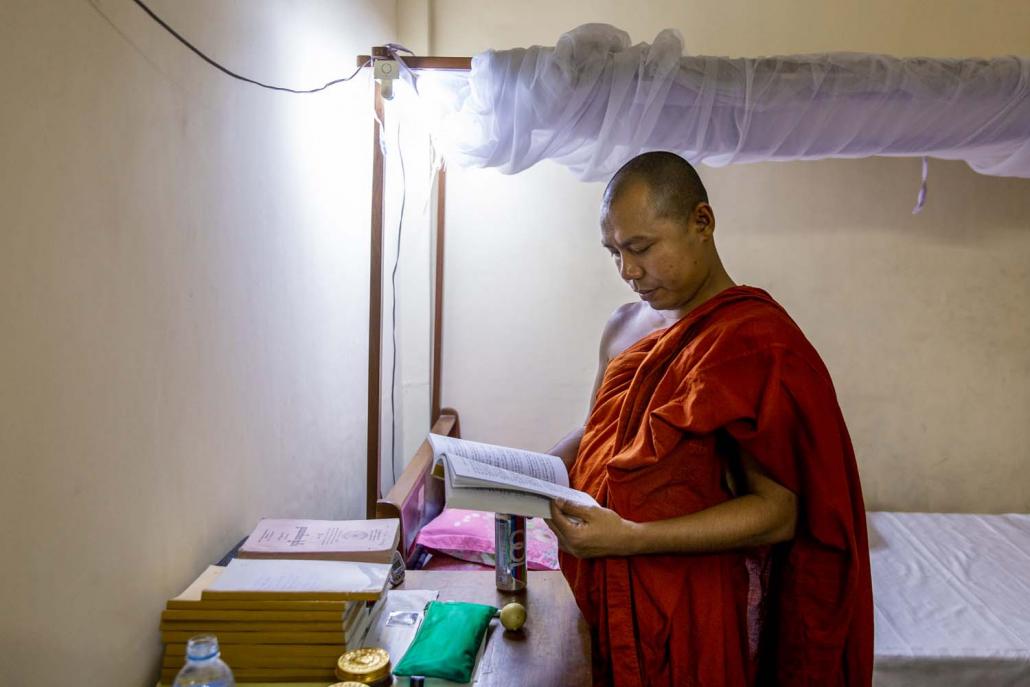

Monks who remain in the sangha for an extended period of time are expected to sit the often gruelling examinations that test their knowledge of the Theravada Buddhist Canon. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

The first is the vinaya pitaka, or basket of discipline, which refers to the 227 rules that govern the life and behaviour of a monk as well as the etiquette that applies to relationships among monks and between the sangha and laity. The vinaya pitaka includes the four offences for which the penalty is expulsion from the sangha for life.

They are sexual intercourse with a man, woman or any living being, taking what is not given (stealing), intentionally causing the death of a human, and falsely claiming to have achieved high spiritual attainment. The other rules include invocations to refrain from using intemperate language, accepting and using money, touching or being alone with a woman, digging the earth, and keeping an extra robe for more than 10 days after receiving a new one.

Second is the sutta pitaka, or basket of suttas, comprising more than 10,000 suttas, or discourses, delivered by the Buddha and his close disciples. One of the best-known books of the sutta pitaka is the Dhammapada, a collection of the Buddha’s teachings expressed in verse. Verse five states: “Hate is never conquered by hate, hate is only conquered by love; this is the eternal law.”

Third is the abhidhamma pitaka, comprising seven books, which offer a detailed analysis of the principles that govern mental and physical processes. The abhidhamma has been described as containing the profound moral psychology and philosophy of the Buddha’s teachings.

There are three categories of examinations for monks. The first is the thamanaykyaw exam for thamanay, or novice monks, below the age of 20. The other tests, in order of status, are the bhivamsa exam and the tipitakadhara-tipitakakovida exam.

The thamanaykyaw exam is set by the monastery where the novice lives and is difficult to pass. A novice who passes this exam before he turns 20 is entitled to add the title “lankara” to his ordination name.

Thamanaykyaw exams are usually held from October to January. There are three grades of exams and they test a novice’s knowledge of Buddhist scriptures, the vinaya, Pali grammar, and the Jataka stories about the 10 previous lives of Gautama Buddha. Novices need to memorise nearly 5,000 pages of text to pass these written and oral exams, said Sayadaw Jagara Lankara, a revered teacher who lives at the Zaydawun monastery in Yangon’s South Okkalapa Township.

Each year up to 800 novices sit for this exam, but the number who pass can be counted in two digits.

Hkun Lat | Frontier

The ‘monk-killing exam’

The bhivamsa exam is the oldest and most prestigious that a monk can sit in Myanmar. It is so arduous that it is nicknamed the “monk-killing exam”. It originated in Mandalay in 1885, the year Burma’s last monarch, King Thibaw, was dethroned by British colonialists and exiled to India. It is also known as the thekkyathiha exam because it was initiated by the Thekkya Thiha Organisation and is held under the supervision of senior monks.

It is in two stages, of which the first involves learning and must be passed by the age of 27, and the second involves teaching, and must be passed by 35, and a monk who does so is entitled to have “bhivamsa” added to his ordination name.

This exam tests both monk’s knowledge of the Buddhist scriptures and their analytical thinking. Only tens of monks pass the bhivamsa exam each year, said Sayadaw Wiratha Bhivamsa, who lives at the Zayakone monastery in Mandalay.

Monks with the title “bhivamsa” are likely to attract many monks to their classes and have large followings among laity.

U Wirathu, who is notorious for propagating hate towards Muslims and was described by Time magazine as “the face of Buddhist terror”, earned the title bhivamsa, which is one reason why he has many followers. He is a fugitive from justice after being charged last year with sedition.

One of the most famous holders of the title is Dr Nandamala Bhivamsa, the former rector of the International Theravada Buddhist University in Yangon’s Mayangone Township.

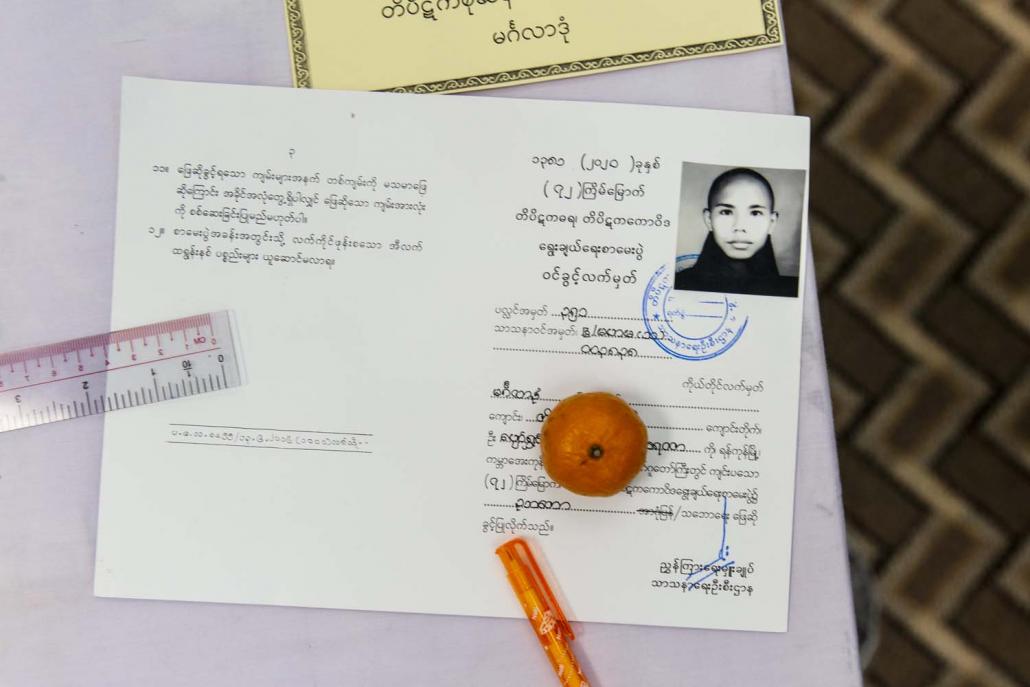

The tipitakadhara-tipitakakovida exam is one of the world’s most gruelling tests. Held each year in the artificial cave at Yangon’s Kaba Aye Pagoda over 33 days, it is an exhaustive test of a monk’s knowledge of the Buddhist Canon. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

A month-long exam

The tipitakadhara-tipitakakovida exam, which is set by the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture, is perhaps one of the most gruelling tests in the world. This written (tipitakakovida) and oral (tipitakadhara) exam is held each year in the artificial cave at Yangon’s Kaba Aye Pagoda. The exam takes place over 33 days between 8am and 4pm and is an exhaustive test of a monk’s knowledge of the tipitaka.

Any novice or monk who has reached at least the first grade of the thamanaykyaw is eligible to sit for these exams.

The exam was first held in 1948, the year of independence. Tipitakadhara is the suffix title bestowed on monks who have memorised and mastered the tipitaka, which comprises more than 8,000 pages. Tipitakakovida is the suffix title honouring those who can write all the scriptures. Only 15 monks have passed both exams and have earned the right to be called tharthana azarni, which means “hero of the sasana”, or Buddhist religion. The exam questions differ for each monk and a different pitaka is tested each year.

In oral tests, two monks sit beside the examination candidate and are entitled to prompt him up to five times in a day. If a candidate needs to be prompted more than five times, he fails the exam.

About 100 monks sit this exam each year. There were 108 candidates for this year’s Tipitakadhara-Tipitakakovida exam, held between December 28 and January 29.

Settanana Lankara, 46, passed the Tipitakadhara after 15 years of trying. He will sit the Tipitakakovida next year.

“I am trying to fulfill the duty of a monk and I believe I will fulfill my duty before I die,” he told Frontier.

Daw Tin Tin San, assistant director of the examination department at the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture, said monks need to study extremely hard to sit the exam, and this takes a toll.

“When they have to study thousands of pages of texts, they tend to have neurological and digestive problems,” she told Frontier.

Monks who have attained the Tipitakadhara-Tipitakakovida title are provided with free travel by the government.

The most distinguished recipient of the title is the Mingun Sayadawgyi, also known as Wicitasarabhivamsa, who became the first to pass the exam in 1954 after reciting the tipitaka free of error and without any prompting. For this impressive feat, the government in the same year bestowed on him the title “maha”, which means “great”. His full title was Mahatipitakadharatipitakakovida. In 1985, seven years before he died at the age of 82, he was listed in the Guinness Book of Records for the person with the best memory in the world.

Hkun Lat | Frontier

Titles, honours

As well as the titles awarded as a result of passing exams, the Department of Religious Affairs also bestows honours on monks for other impressive achievements.

There are more than 20 such titles, including aggamahapandita, which can be translated as meaning “possessed of the superior knowledge”.

“These titles are bestowed for their achievement in the promotion, propagation and purification of the tharthana,” said Tin Tin San.

“If a monk has a long suffix or title, you can be sure it was bestowed on them by the government,” she said.

There are monks who do not have any titles and they include those who belong to the Shwegyin sect, who do not sit for any exams.

Shwegyin is one of nine sects, or gaing, in Theravada Buddhism in Myanmar, the largest of which is Thudhamma.