Despite many challenges, non-junta schools are enabling tens of thousands of children throughout the country to resume their education after more than two years of disruptions.

By FRONTIER

Seventeen-year-old Ko Nyi Nyi* has not attended classes since his high school closed in March of 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Following on its heels came the Civil Disobedience Movement, which saw tens of thousands of teachers go on strike in response to the military coup in February 2021.

In June of this year, a delighted Nyi Nyi finally enrolled in a community-funded school in Sa Thein village in Magway Region’s Pauk Township after 27 months of not being able to continue his education.

“I am so happy that I could return to school, even though we don’t have enough books and stationery and we have other needs,” Nyi Nyi, who spent all of last year working on the family farm, told Frontier.

However, not all is well in Sa Thein. Nyi Nyi and his classmates are constantly on the alert. Magway Region has been the subject of some of the most brutal attacks by the military since the coup, and although his school is in an area controlled by the People’s Defence Forces, the students fear that their school could be closed again and they would be forced to flee.

“I worry that the military will come. We all keep attending classes with that same concern,” he said, adding that he also wants to return to the normal, peaceful student life he enjoyed before the coup.

Despite the dangers, students like Nyi Nyi continue to refuse to attend the state schools now being run by the military regime. When the academic year began in June the junta launched a campaign aimed at persuading parents to send children to schools under its administration, but many have instead flocked to alternative institutions run by ethnic education providers, the National Unity Government and also some civil society organisations.

These alternative schools have already demonstrated success in getting children to resume their education outside of military-controlled institutions. However, those involved in reopening schools in areas under the control of PDFs and other anti-military armed groups operate in an atmosphere of constant uncertainty.

“I think it will be a long time before I can fulfil my ambition,” said Nyi Nyi, “it doesn’t seem possible now in the current situation.”

Community-funded education

In addition to safety concerns, schools are also dealing with a lack of funding.

The NUG’s deputy education minister Ja Htoi Pan admitted that the parallel government’s budget is very limited. She has said the NUG is unable to provide financial support for schools that have reopened in areas under the control of PDFs or ethnic armed groups. However, they are providing teaching guidelines and training to teachers who are now working with traumatised students who have missed two years of school.

The funding for these reopened schools now largely comes from local communities and sympathetic donors abroad.

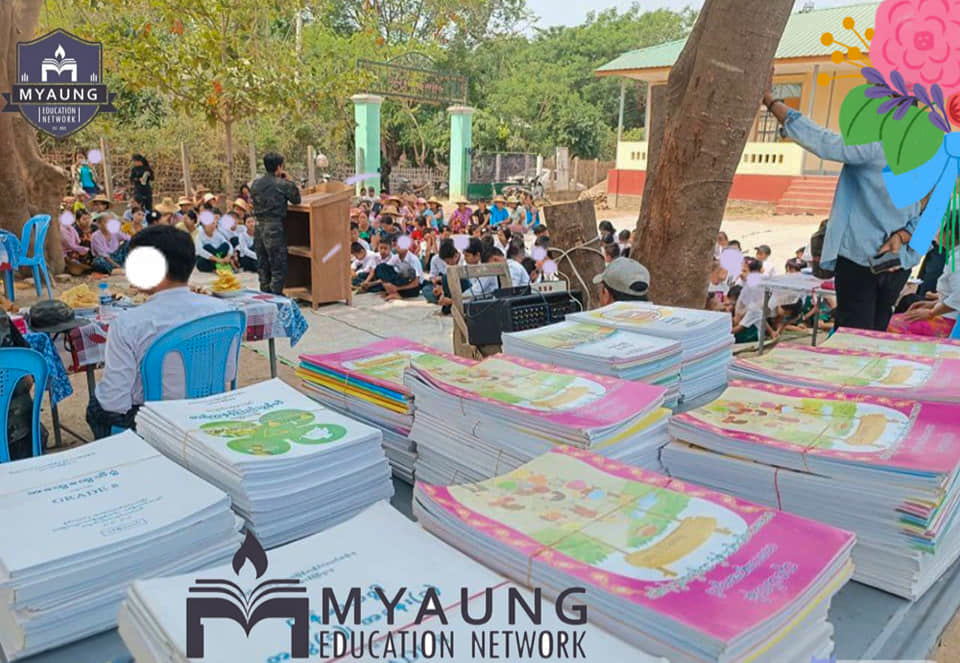

In Sagaing Region’s Myaung Township, 25-year-old Ma Grace* is a platoon commander of the Myaung Women Warriors, a regiment of the Civilian Defence Security Organisation Myaung. She and other members of this local militia founded the Myaung Education Network in February. With the support of overseas donors who wanted to help students in Myaung Township return to learning, the network was able to collect enough money to open 18 schools on March 1, much earlier than in other townships and regions. Despite repeated raids by junta forces in May, according to Grace, the network has now been able to support the reopening of 26 schools.

Salai Yaw Man, 32, is a member of the Mindat People’s Administration Committee, a local governance body established to oppose the coup. He told Frontier that in Chin State’s Mindat Township, more than 100 primary and elementary schools have reopened under the management of the committee, though high schools were yet to reopen in part due to a lack of teachers.

While tens of thousands of teachers have joined the Civil Disobedience Movement, Yaw Man said most of the volunteer teachers in Mindat are older students.

“In our Mindat Township, there are few high school aged students apart from those helping parents on farms. They are the main source of the volunteer teachers at the primary and elementary schools that reopened within the past month,” he told Frontier.

Yaw Man said the Mindat PAC has been providing training to teachers with support from the NUG. In addition to the regular school subjects, teachers are also instructing students on subjects such as landmine awareness, federalism and survival skills.

Village households are donating between K3,000 and K5,000 a month for the teachers and volunteers, said Yaw Man, adding that more than 4,000 students are currently enrolled.

In Magway’s Sa Thein village, a school that was reopened on June 1 is functioning with funding and security support from local PDFs.

“We didn’t have any funds to start running the school; the fund to start running the school was first established by the local PDF groups,” said Daw Khin Win*, 32, the principal of the high school, adding that they only dared to open the school because the PDFs have managed to limit the movement of junta troops in their region.

“The military troops were not able to come into our village after that time and the villagers no longer needed to be prepared to run and hide. We started feeling a bit safer than the previous months. In the area around Sa Thein, there are at least three PDF groups,” Khin Win told Frontier.

Meeting the various challenges has enabled the school in Sa Thein to reopen with 37 teachers and volunteers and provide classes from kindergarten to Grade 11 for more than 300 students. Many of the students are from nearby villages that either do not have schools or where schools are yet to open. Khin Win said that before the closures, this school served around 1,000 students.

“There are many challenges as we are running the schools. We have no income. We don’t have sufficient stationery or other supplies that a school needs. But we are all happy as we are now able to interact again with the children, the students and the practice of teaching that all of us have been so far from for two years,” said Khin Win.

New curricula

The NUG is compiling data about the schools that have opened on a community-funded basis, Ja Htoi Pan told Frontier. At least 150,000 students have enrolled at schools in areas beyond the control of the military council, she added.

“The movement standing against the slavery education system under the military was not started by the NUG. It is a movement that the entire public is engaged in,” she said. Many in Myanmar refer to the schools run by the military as “slave education”.

She said that the NUG has launched a comprehensive review of the curriculum being taught at the reopened schools.

Ma Tresa*, 34, who is the head of the Myaung Education Network, said that although her organisation has received little funding, it has received teaching materials from the NUG.

“What they are giving us now is training for the teachers, using video clips on memory sticks,” she said, “we give the NUG [enrolment] data and information and in return it will give us letters of recognition, which are like certificates of each school’s legitimacy.”

The NUG deputy education minister said that the reason schools are being asked to provide this data is for the ministry to be able to recognise the credentials of matriculated students who apply to universities under NUG administration.

Ja Htoi Pan said that the NUG education ministry is focusing on recognising schools that have reopened in PDF or EAO controlled areas.

For many families, attending these schools is an overtly political act, and the revolutionary fervour sometimes extends to not just where students attend school but how schools are conducted. According to students, some of these schools start the day by singing revolutionary songs before starting instruction.

“The education sector is like a battlefield between the military and the people and since day one of our Ministry of Education we have always considered how to provide an interim education for our children. We don’t want to go backwards; we want to move forward,” said Ja Htoi Pan.

The Myaung Education Network has also been working with teachers to adjust their method of delivery. It has asked teachers to use storytelling to make learning more interesting and engaging, instead of the more traditional lecture and rote memorisation-based method of teaching that can be boring for students.

The ever-present risk of junta raids has meant that students also receive instruction on the safest ways of fleeing attacks and on surviving if they need to hide in forests. Ma Tresa said pamphlets have also been prepared for primary level students to make them aware of the danger posed by mines and unexploded ordnance.

Ma Zin Zin*, 17, is a Grade 11 student at the school in Pauk Chaung village, not far from Myaung town. She is also back at school after two years of absence.

She said that her school does not have enough teachers and struggles to provide all the children with basic supplies, such as textbooks, purified drinking water and uniforms. Due to the lack of instructors, some teachers also find themselves responsible for instructing multiple grades in a day.

“Some students lost their textbooks when their homes were burnt down by the military, so we have to share and use the same textbooks together,” said Zin Zin, who added that her ambition is to be a teacher, and she wants her country to return to what it was before the coup.

“If I had not been able to return to school, I would have had to work with my parents for a living and I would have gotten older and older without a chance to continue learning,” Zin Zin said.

Her concern about the possibility of junta forces returning to the village is shared by her classmates, but she said that returning to school has given her hope for a better future.

Digital Dangers

In recent weeks, the junta has been putting increasing efforts into cracking down on the growing parallel education sector. Since the movement began, CDM staff, especially teachers, have been a major target for arrest, but starting in mid-July rumours began to swirl that the military had set their sights on one NUG-affiliated online school in particular — Kaung for You.

The crackdown started in early July, when parents of students at the school began to report that they were receiving threatening phone calls about their children’s enrolment in the school. As of this reporting, at least 10 Kaung for You teachers are now confirmed to have been arrested by junta, including the founder of the school, Kaung Thike Soe.

The school is now temporarily closed and the Basic Education Students and Youth Association has told families and teachers to cease contact with the school, to avoid using their Telegram, Viber, and other messaging applications and to change their user names and profile pictures on their social media accounts.

The military has claimed that these educators were arrested for their involvement with “illegal teaching programmes”. On July 25, the regime made an announcement that Kaung for You teachers who turned themselves in by August 7 would be “forgiven”.

Ja Htoi Pan wrote on her Facebook page that the NUG education ministry is investigating the incident and that the school has taken responsibility for failing to uphold certain “administrative requirements.” She added that the NUG education ministry is working on a public statement and developing measures to ensure better security of online schools.

The NUG’s human rights ministry condemned the arrests as an “obvious violation of a fundamental human right”, but also admonished the school for failing to protect privacy, which it said was another human rights failure. “Therefore, the respective school administration will be accountable,” the statement promises.

It’s still unclear what exactly led to the arrests, but it looks as though the junta managed to access the school’s database and find the addresses of the teachers and possibly the students as well.

Ma Tresa of the Myaung Education Network said that schools are facing difficulties with storing data securely. She said that while schools want to store the data in a cloud service, lack of internet access means that a lot of the data is being kept on physical hard drives.

“The documents include the lists of students and teachers, as well as documents about school activities… and also the communications with the NUG, and things like monthly reports,” she said. “The internet connection in Myaung is now on and off. But there are also some places in some remote areas where we can use the internet. If we want to upload the data, we have to go to such places first.”

For now, many of the students have gone into hiding as yet another obstacle is placed in the path of their education.