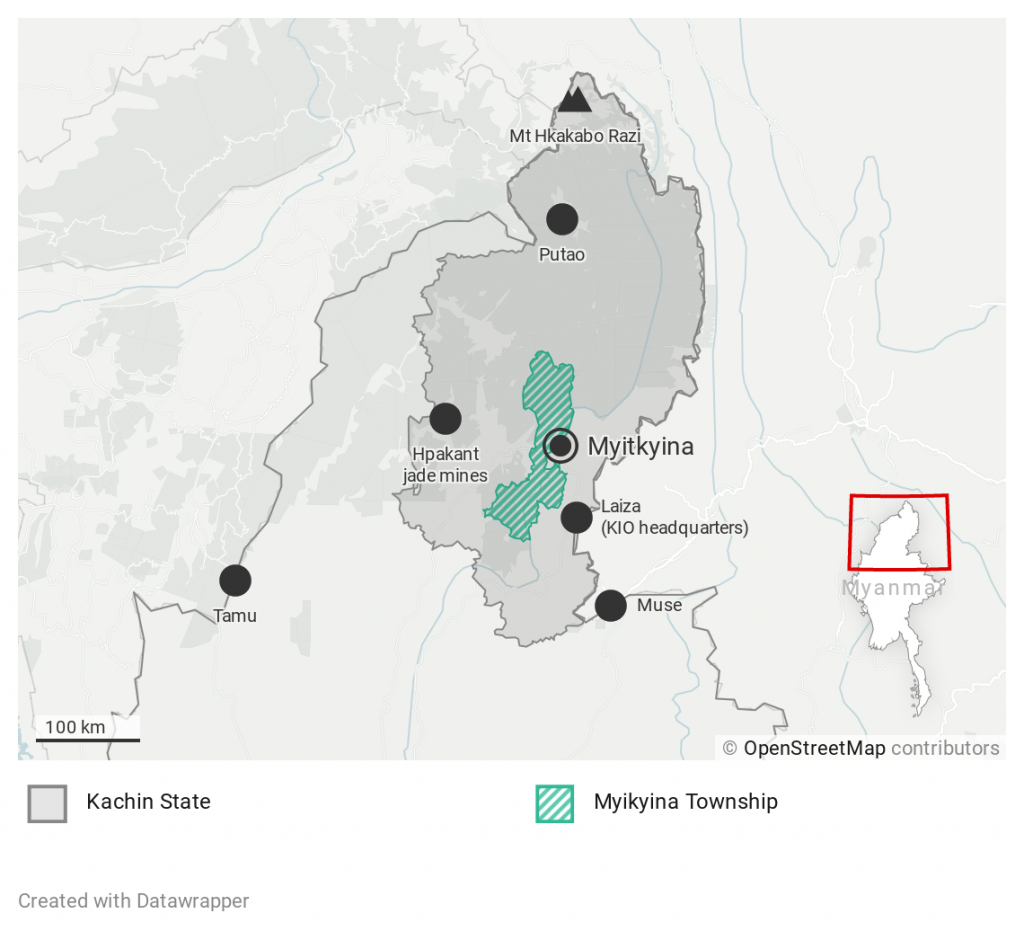

With support for parties split along ethnic lines, the election result in the diverse Kachin State capital will depend on which communities come out to vote, and which stay at home.

This article is part of Frontier’s Tale of Five Elections series. We’re following the election through five townships across the country, capturing events and local voices through the campaign, voting and declaration of winners. Scroll to the bottom for the first two articles on Myitkyina.

By PYAE SONE AUNG | FRONTIER

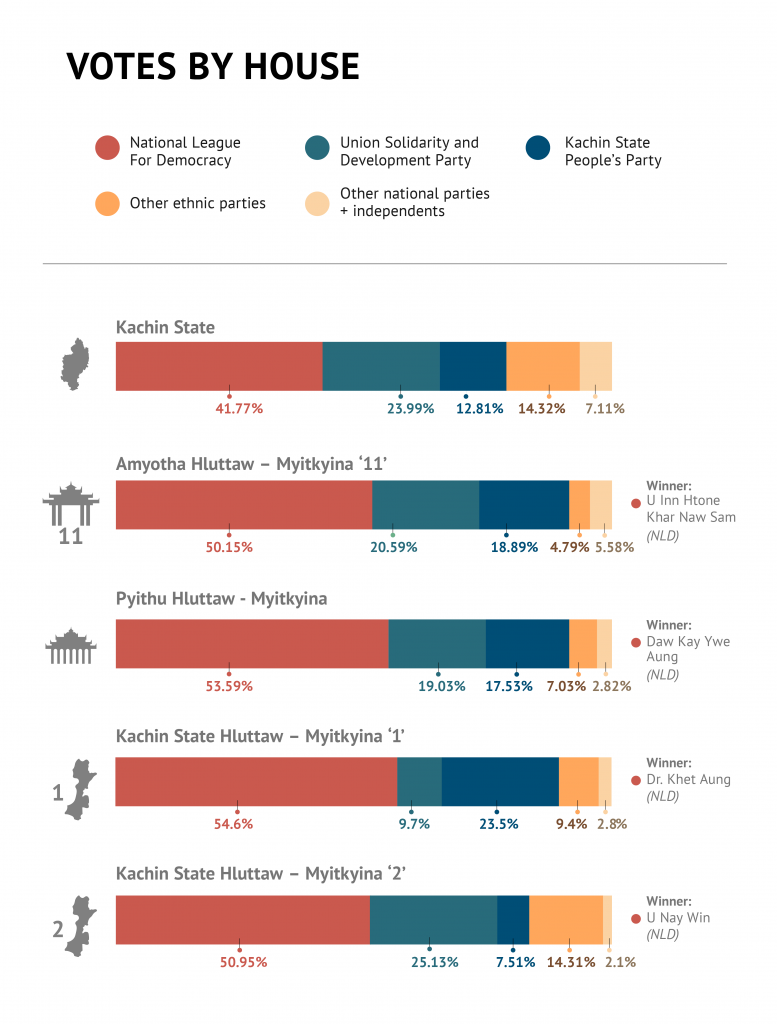

Low voter turnout has emerged as the primary concern for candidates from the Kachin State People’s Party and the National League for Democracy in the Kachin State capital, Myitkyina, as election day approaches.

The city is home to the Tatmadaw’s Northern Command and hosts a large contingent of soldiers and their dependents, who these parties worry may rack up votes for the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party. But the more that civilians turn out at polling stations, the more this military vote will be diluted.

“We are asking the people to be sure to vote and to vote for our party,” Doi Bu, KSPP vice-chair, told Frontier on October 29. She said many elderly and first-time voters in the rural villages of Myitkyina Township, where the KSPP has campaigned heavily, did not know when, where and how to vote.

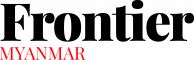

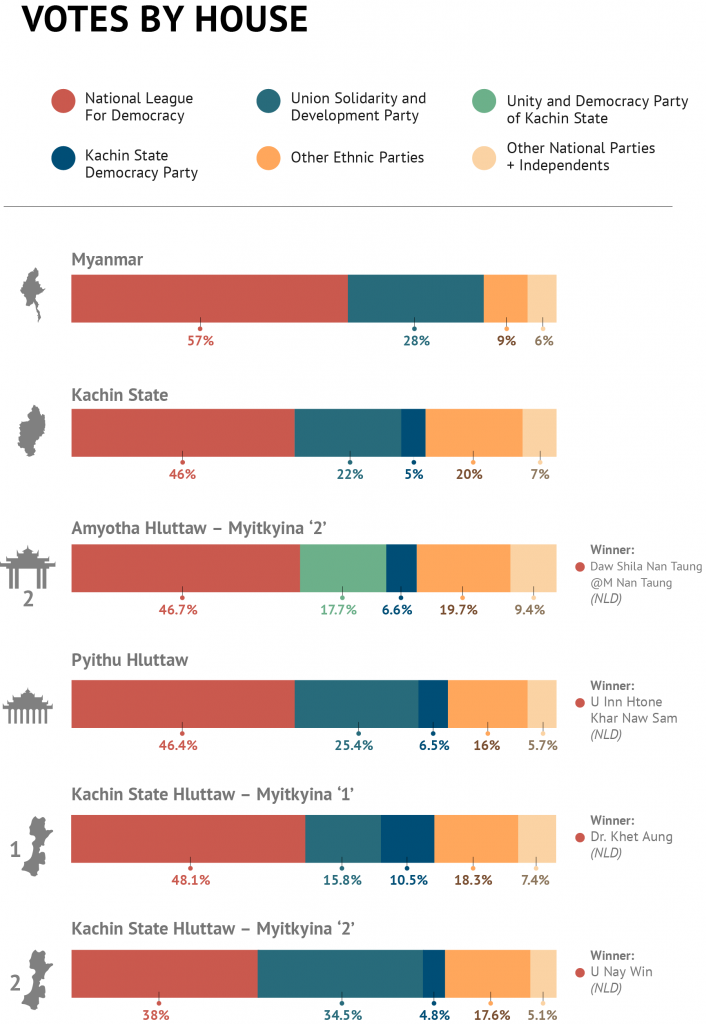

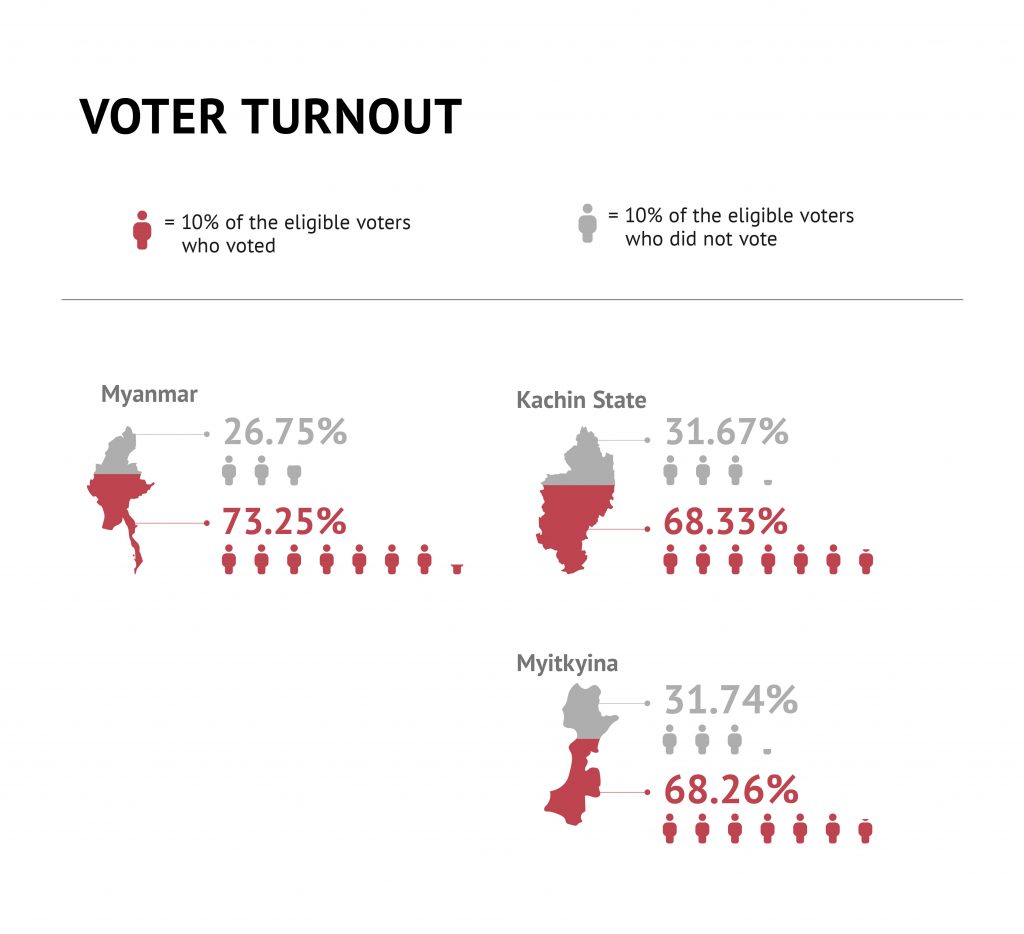

In the 2015 election, about 121,899, or 68 percent, of the 178,579 registered voters cast ballots in Myitkyina, delivering the NLD a clean sweep of both state hluttaw seats and a seat each in the Pyithu Hluttaw and Amyotha Hluttaw. However, the USDP won the Amyotha Hluttaw seat of Myitkyina-2 in a 2018 by-election, a result partly attributed to very low turnout among the civilian population coupled with high military turnout.

“People were not as well-informed or interested in the by-election as they were in the [2015] general election, while the USDP could rely on its hardcore voters in both elections,” Ndung Hka Naw San, the NLD candidate for the Amyotha Hluttaw seat of Kachin-11, told Frontier on October 28.

About 230,000 Myitkyina residents are eligible to vote this year.

“If 80 percent of eligible voters in Myitkyina vote on election day, I am fairly confident that victory will be ours,” Ndung Hka Naw San said.

However, the KSPP, which was founded a year ago by the members of four Kachin parties in a bid to avoid a split ethnic vote, has quickly gained popularity and emerged as a strong rival to the NLD. There’s concern in both parties that, even with a high turnout, vote splitting between the two could mean the votes from Tatmadaw personnel and their families equal enough to tilt seats to the USDP in Myitkyina.

This year, the UEC has ordered military voters to join the general population in casting their ballots outside military cantonments – a decision aimed at greater transparency – but many still doubt that they will be able to vote freely.

Will the migrant vote tip the balance?

Besides soldiers and their families, Myitkyina is home to a large population of internal migrant workers, and there’s disagreement over how much they could influence the election. Ethnic parties worry that, because many of these migrants are Bamar, they could give the NLD or USDP the edge. This concern was heightened when, earlier this year, election by-laws were amended to enable internal migrants to register to vote in an area after only 90 days’ residency, down from 180 days previously.

Ethnic parties including the Kachin National Congress and the KSPP loudly protested this change. “We objected, but the UEC proceeded anyway,” said Doi Bu. “Migrant workers haven’t the slightest knowledge about ethnic parties, but they know the ruling NLD and the USDP, which they will vote for.”

“It is not fair that they lose their voting rights [when they change address], but it’s also not fair to us that they can decide the fate of Kachin State after living here for only 90 days,” said Paw Lu, a member of the Kachin Youth Movement. He suggested migrants be able to cast votes from wherever they are, but only for candidates running in their home constituencies.

NLD chair and state counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi responded to these concerns by saying the NLD was a “Union” party that represented all ethnic groups, but that has only angered ethnic party members more. Seng Nu Pan, the KSPP candidate for Myitkyina’s Pyithu Hluttaw seat, called it “an insult” to suggest that the NLD could represent the interests of Kachin people.

But despite their potential to swing local races, others stress that actual turnout among migrant workers will be low. This partly due to a lack of interest on their part but also because of the burdensome procedure for transferring your vote from your home constituency to your current place of residence. To complete the required Form 3A by the October 10 deadline, applicants had to supply an endorsement from their employer or local ward or village tract administrator, among other documents.

“Tons of documents were needed to register,” said Ko Yan Aung Htun, a freelance journalist who moved to Myitkyina from Yangon three years ago. “The village tract and ward election sub-commissions asked migrant workers to provide a household registration list, National Registration Card [officially called a Citizenship Scrutiny Card], recommendation letters from the police and their employer – all sorts of documents,” he said.

U Myint Htay, 42, a Bamar migrant who lives and works on one of 30 tissue culture banana plantations run by the Chinese-owned Power Five Star Co Ltd in Myitkyina, estimates that few among the plantation’s 1,500-strong migrant workforce will be able to vote.

“We [banana plantation workers] are quite separated from the outside world and many of us are not registered to vote [locally],” he told Frontier on October 28.

He himself is registered in Myitkyina, however, and he plans to vote for the NLD. He and several other workers at the plantation were assisted in registering by members of the NLD, who had an obvious incentive in helping migrants in this way.

Myint Htay, who had moved to Kachin from Myaungmya Township in Ayeyarwady Region, defended the right of migrants to vote locally, which he said was the only thing that kept them from disenfranchisement.

“We can’t return to where we were originally registered, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, but we want to vote for the party that we support,” he said

A curbed campaign

Campaigning in Myitkyina, like elsewhere in Myanmar, has been muted by COVID-19 restrictions and mainly reduced to door-to-door canvassing. But in recent weeks KSPP and NLD supporters have staged huge election convoys joined by hundreds of people.

“More than one thousand KSPP supporters toured Myitkyina on bikes before heading to the site of the Myitsone dam, making detours to small towns along the way,” Ma Esther, a reporter with local newspaper Myitkyina News Journal, told Frontier on October 27.

The big campaign events might have been an effective form of electioneering, but they attracted stern criticism from some Myitkyina residents and gradually faded away.

“The party central executive committee appealed to our supporters, especially the youth, to refrain from forming big crowds,” Doi Bu said, adding that the KSPP also wanted to avoid the campaign-related violence that has occurred between NLD and USDP supporters elsewhere in Myanmar.

The USDP, on the other hand, has run a disciplined campaign in Myitkyina, eschewing big events in favour of low key, local canvassing. “It is campaigning in other ways, such as by distributing face masks, sanitising gel, and t-shirts door-to-door,” said journalist Yan Aung Htun.

USDP representatives did not answer repeated phone calls from Frontier.

But the big three are not the only parties in town. Other contenders include the Kachin National Congress, Union Betterment Party, National Unity Party, Tai-Leng (Shanni) Nationalities Development Party and Lisu National Development Party. The latter two cater to sizeable ethnic minorities within Kachin State.

Myitkyina is a diverse city in a diverse state, and winning seats on Sunday will depend on cobbling together blocs among its multiethnic population – and then getting them to turn out on the day.