For the first time in 76 years, the only surviving granddaughter of King Thibaw spoke recently in public in Yangon, where her family has been living quietly since 1919.

By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER

On the evening of March 24, Princess Hteik Su Phaya Gyi, granddaughter of King Thibaw, the last King of Burma, addressed the Yangon Rotary Club. The last time the princess, 92, had addressed the club she was 16 and she spoke about recent student protests that had left one student dead. Among her audience was Reginald Dorman-Smith, the Governor of Burma.

For her second address at the club, 76 years later, the place was packed again – at least by the standards of its weekly meetings. Club members and journalists (including this one) leapt at the opportunity to see a member of Myanmar’s royal lineage.

“I just had a little bit of an understanding of the background from history books, but I didn’t know they were living in the city,” said Sam Britton, a club member.

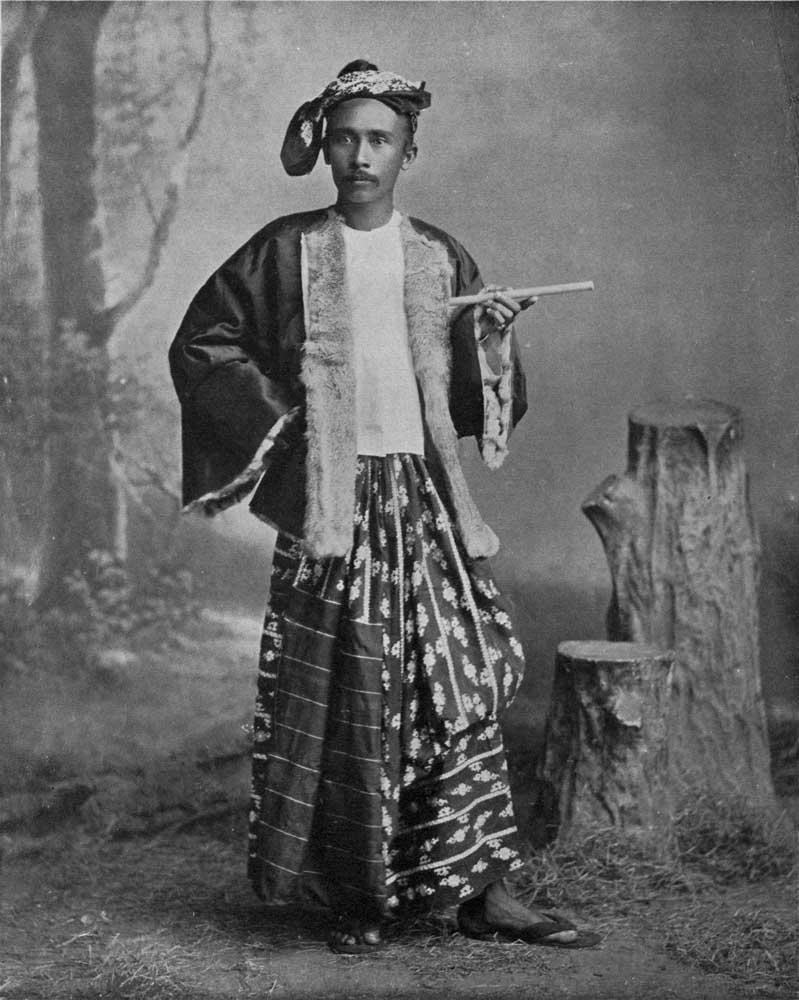

Like many of those present, he had thought of the royal family as a long-lost piece of Myanmar’s pre-colonial heritage, which faded away after a British flotilla sailed into Mandalay in 1885. Although the exile of the royal family to India is a cornerstone of Myanmar’s history, the family’s return in 1919, three years after King Thibaw’s death, was all but overlooked by history as members of the royal family settled into their lives as ordinary citizens.

“They were allowed back by the British but were kept in internal exile,” said British historian and filmmaker Alex Bescoby. “When independence came, the new government was supposed to keep paying them a pension, but it never happened. They mostly disappeared into history.”

Bescoby, of Grammar Productions, is producing a documentary called “Burma’s Lost Royals,” which will show the modern history of Myanmar through the life stories of King Thibaw’s surviving descendants.

“The exile of the king in 1885 is a seismic moment in modern Burmese history, and in that moment you find the roots of the conflicts and divisions and problems that Burma has had ever since. This pretty unusual family have had a unique vantage point on that story that more people need to know about,” Bescoby said.

He has spent the last two years with scattered family members, who made a living as English teachers, staff at foreign embassies and a variety of other less-regal careers. Princess Hteik Su Phaya Gyi worked as a private tutor, married and had six children. Her brother Prince Taw Phaya, now 92 and the only other surviving grandchild, became a businessman. His niece, Daw Devi Thant Cin, is a prominent environmentalist, and his nephew, U Soe Win, was until last year manager of the Myanmar Under-19 football team.

“For our whole family to be exiled to the very furthest part of India near the Arabian Sea, we are very lucky to be here again,” said Soe Win. He views his family’s plight with Buddhist acceptance, but laments Myanmar’s neglect of its royal history since colonialism.

He described a recent trip with Bescoby to his great-grandfather’s grave in India. “We managed to discuss our shared history, British, Indian and Myanmar. The last king of India is also here [in Myanmar],” he said. “It’s not natural. We want to take the King back. We have to maintain this as a heritage for future generations not to forget our history,” he said.

Bescoby says the royal family was considered a dangerous element to the British and subsequent regimes. “In the early years the military government were actually quite jealous of the affection they received from the public, and the military, like the British, never wanted them to be a rallying point,” he said.

Yet Myanmar is growing more aware of its forgotten royals. A recent reunion in Mandalay brought together nearly all surviving members of the royal family for the first time since the exile in 1885.

“We have to revive, not to get power, but to have some space in the community,” Soe Win said. “Now we are starting to get some space. Space means we have some right to talk among our countrymen.”

Asked if Myanmar would see a resurgence of cultural monarchism, Princess Hteik Su Phaya Gyi graciously declined to comment. Instead, she spoke about being a teenager in a British boarding school, working as a secretary to General Ne Win’s brother-in-law, and how her mother would always be sure to place a flower in her hair, a tradition of the Burmese royal court, “to remind them that you are majestic”.

She also declined to comment on politics, saying only, “It is too short a time for the present or the future. But we expect the best.”