A short guide to the events, politics and legacy of Burma’s decades under British India.

By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER

AFTER THREE disastrous wars with Britain, the once-fearsome Alaungpaya Dynasty lay in tatters, and in 1886 the rest of the kingdom was officially annexed into British India.

The next five decades would be Myanmar’s colonial era, which some say ushered the country into modernity, and others argue set the stage for decades of isolation and civil war.

British bureaucratic bounty

The colonial period began with the dissolution of the royal court in Mandalay. King Thibaw, only 26, and his family were exiled to Ratnagiri on India’s Arabian Sea coast, and most of his nobles and courtiers either followed him there or relocated to other parts of what was then known as Burma.

The Raj, the administrative system of the British Indian government, supplanted the old royal traditions, and Mr Charles Bernard became the first Chief Commissioner of a united Burma.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

When Thibaw’s court collapsed, many areas descended into insurgency or outright lawlessness. In the early years after the annexation of Upper Burma, maintaining stability was the top priority for the British.

Although the Raj had a well-structured hierarchy of governors, divisional commissioners and sub-divisional officers, it exercised direct and sometimes tyrannical control over certain areas, and left others (such as the well-established Shan kingdoms) with a measure of autonomy.

Ministerial Burma, or “Burma proper”, comprised Tenasserim, Arakan, Pegu and Irrawaddy divisions. Scheduled Areas (also known as “secluded areas” or “frontier areas”) included the Shan kingdoms, Chin Hills and Kachin tracts.

The 19th century: A rice nation

By the time Thibaw was sent into exile, Britain had been in control of the southern half of Myanmar, known as “Lower Burma”, since the end of the Second Anglo-Burmese war in 1853, with the port city of Rangoon as its base of operations.

The British encouraged rice cultivation in the Irrawaddy Delta as an export crop. An international rice shortage caused by the American Civil War followed by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 helped to make rice Burma’s most important industry. Burma was the world’s biggest rice exporter for much of the first half of the last century, when it was known as “the rice bowl of Asia”.

typeof=

After 1853, Lower Burma became a haven for businessmen and gentry dissatisfied with the monarchy and smallholder farmers looking to make a new start. Chettiar moneylenders poured in from southern India to fill the demand for capital, along with hundreds of thousands of Indians keen to seek out new opportunities.

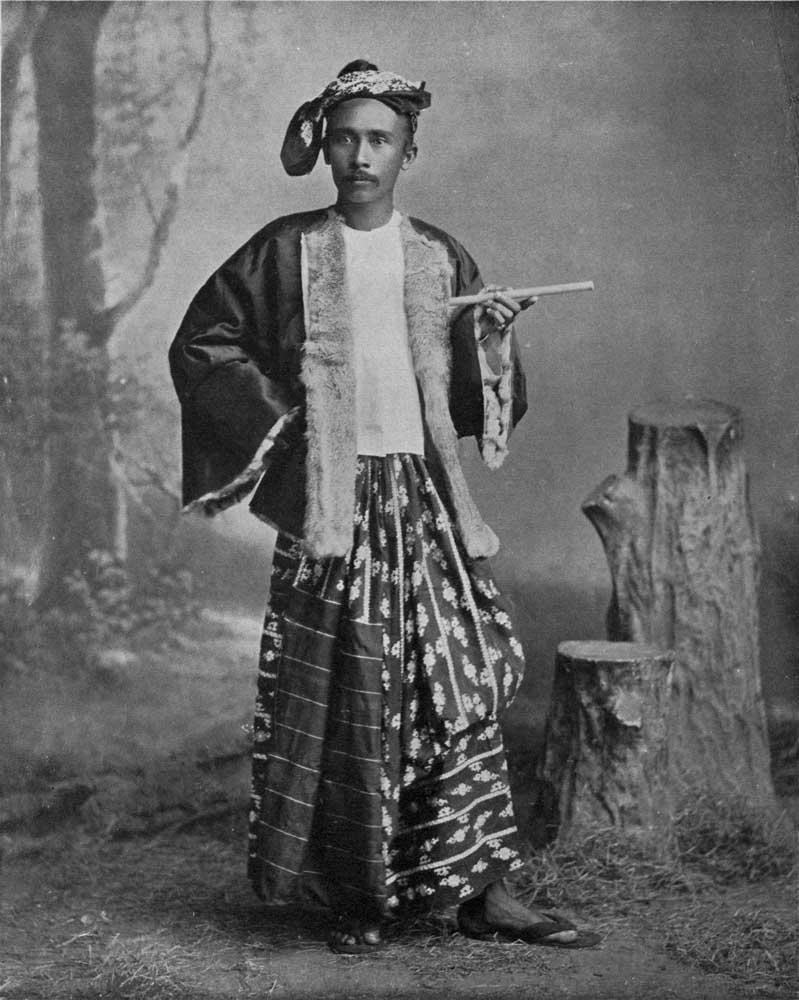

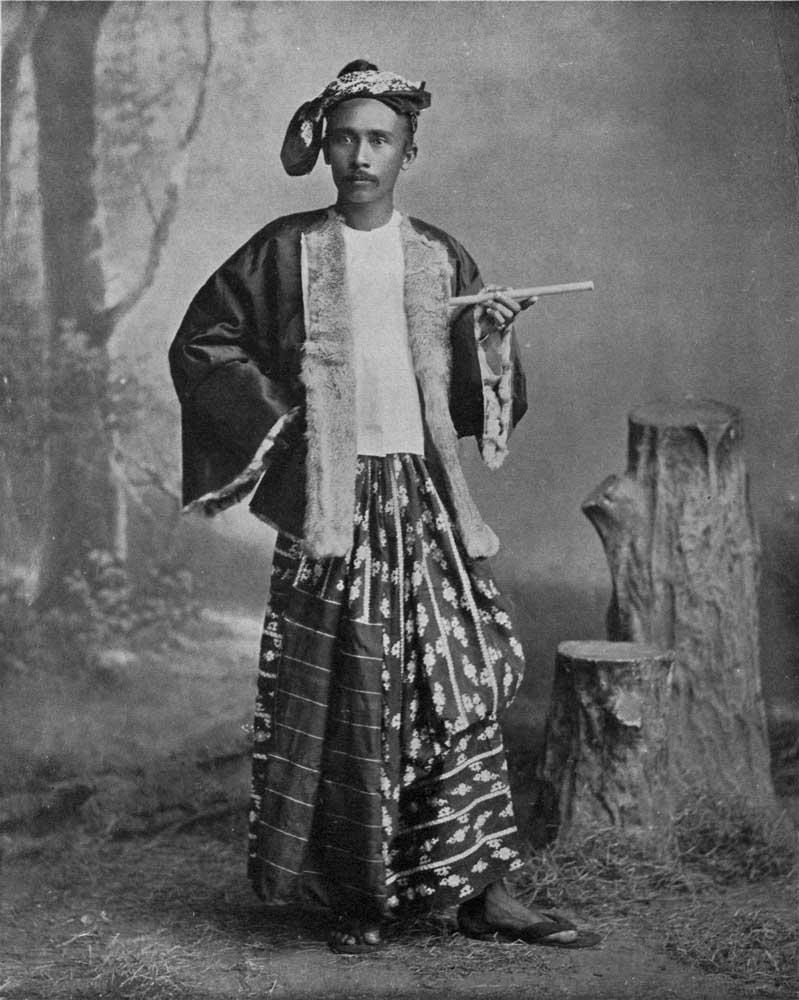

The Indian influx would continue throughout the colonial period and shape many aspects of daily life in Burma and, especially, Rangoon, from religion to dress. (The modern Myanmar longyi ensemble, largely inspired by Indian fashions, became popular during this period.)

The 20th century: Burma comes into its own

After World War I, which shook up the British Empire and marked the beginning of its end, Burma began to gain its own political identity.

A new generation of young, educated Burmese, many of whom had studied in Europe, began to question the inequality of colonial culture and become politically active.

They organised under bodies such as the Young Men’s Buddhist Association, formed in 1906, and later the Rangoon University Student’s Union, established in 1931.

The struggles for home rule in other parts of the empire, especially by the Irish republicans and Mahatma Gandhi’s Indian National Congress, fermented growing nationalist sentiment in Burma. Well-respected newspaper The Sun, founded in 1911, was a proponent of the Burma nationalist movement.

In 1920, a student boycott of Rangoon University became one of the first major nationalist demonstrations against British rule (an event marked each year by National Day, which falls on the 10th waning day of Tazaungmone). For the rest of the decade Burma won the beginnings of political autonomy with a new diarchy constitution and its own Legislative Council, although these reforms did not extend to the Shan kingdoms and other frontier areas.

However, discontent with British rule only grew worse. The Great Depression of the 1930s devastated the rice industry, and therefore the Burmese economy in general, and the nationalism that sprouted in the 1920s became more extreme.

In 1929, a monk named U Wisara was arrested for sedition after spreading anti-colonial rhetoric. He died in prison during a hunger strike and became one of Burma’s first nationalist martyrs.

In 1930, a former monk named U Saya San started a tax protest that grew into a rebellion involving about 3,000 fighters. It took the British two years to finally put down the revolt. In that same year, a group of young people founded the Dobama Asiayone (“We Burmans’ Association”), a relatively radical nationalist group whose members referred to each other as “Thakins” (“masters”), a term of respect reserved for addressing foreigners.

One year later, Ko Aung San and Ko Nu (later to become General Aung San and Prime Minister U Nu) were expelled from Rangoon University for refusing to disclose the author of an inflammatory university magazine column. The resulting student strike kicked off a wave of university protests, and Aung San and U Nu soon became active in the Dobama Asiayone.

The 1935 Government of India Act officially separated Burma from India and paved the way for its first home-rule government, though Britain still held ultimate power. In 1937 the nationalist lawyer U Ba Maw, who defended the insurrectionist Saya San at trial, was elected as Burma’s first Chief Minister.

The newly formed Burmese government was far from stable and the outbreak of World War II in 1939 would make matters worse. The war was a time of extreme political tension, but Myanmar would eventually emerge a fully independent nation.

The colonial legacy

The lasting impact of British rule on Myanmar is debatable. Some argue that the British ushered the nation into the modern era, others that it sowed the political, class and ethnic tensions that defined Myanmar through the 20th century, and still do today.

For better or worse, the lasting remnants of the colonial period go beyond the old buildings in downtown Yangon.

In particular, Myanmar law was more or less written by the British; the code of criminal procedure was drafted in 1898 and the penal code in 1861, before the third Anglo-Burmese War.

Colonial-era laws on the parliamentary shortlist for reform include the 1914 Myanmar Companies Act and the 1894 Land Acquisition Act.

The sun rises over the royal palace in Mandalay. (AFP)

Other laws are more controversial. The 1923 Official Secrets Act and the 1908 Unlawful Associations Act are still sometimes used to target political activists and the press.

Since political and economic reforms began in 2011, the new parliament has been working to amend some of these laws, but the process is slow.

Yet, the fact that Myanmar’s laws are old and authored by a colonial power does not necessarily make them ineffective, argued Dr Daniel Aguirre, a Yangon-based legal adviser for the International Commission of Jurists.

He explained that Myanmar’s legal system is based on common law, known in Latin as stari decisis, which strongly adheres to a precedent set by previous cases.

In India, whose legal system is based on the same colonial foundations, the old laws function because they have a century of precedent behind them and courts that properly apply that precedent.

In Myanmar, however, the judiciary was more or less laid aside for 50 years, and in many cases the law has not been applied properly. Even where the laws are not outdated, they are often misapplied or ignored.

For example, the controversial Article 295(a) of the Penal Code, which broadly outlaws inflammatory language against a particular religion, was originally designed to uphold religious harmony in British Indian provinces. Critics argue that it has been misapplied to provide special protection only to the Buddhist establishment, which is almost the opposite of its original intent.

That is not to say that the colonial system was a paragon of justice. “Obviously a British trader would have better opportunities in a court than a Burmese worker,” Aguirre said. “We have to be careful to not say that things were better back in the colonial days. They clearly weren’t.”