Kachin State People’s Party members are split on who or what is to blame for their election failure on November 8 – but they’re sure it’s got nothing to do with them.

This is the final article about Myitkyina in Frontier’s Tale of Five Elections series. We have followed the election in five townships across the country, capturing events and local voices through the contest and its aftermath. Scroll down for the first three articles on Myitkyina.

By PYAE SONE AUNG | FRONTIER

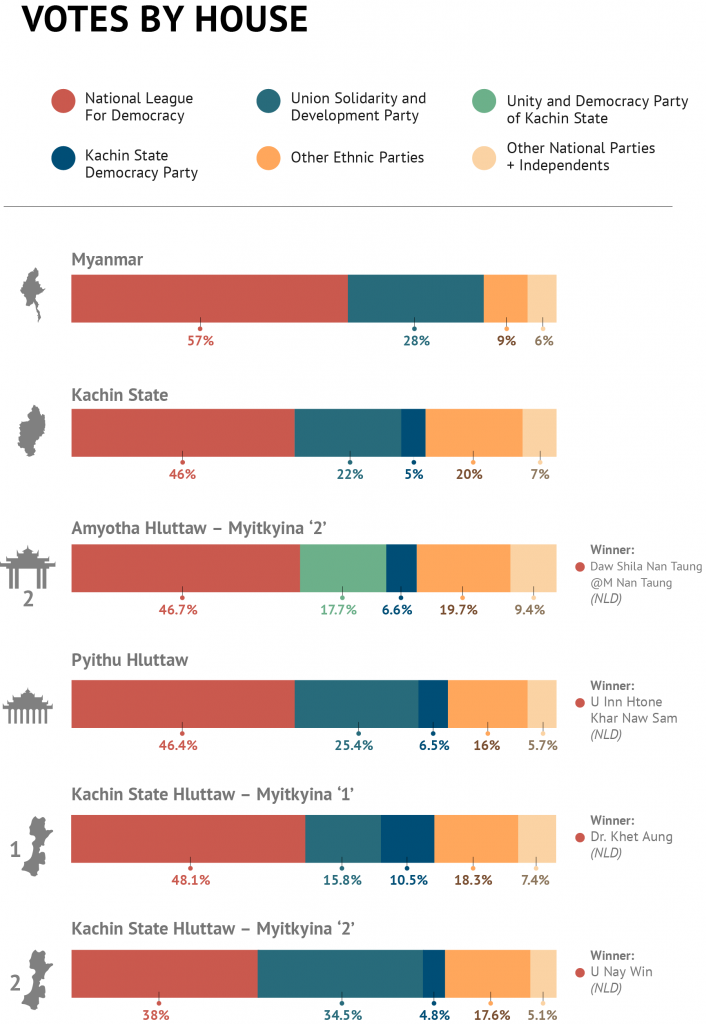

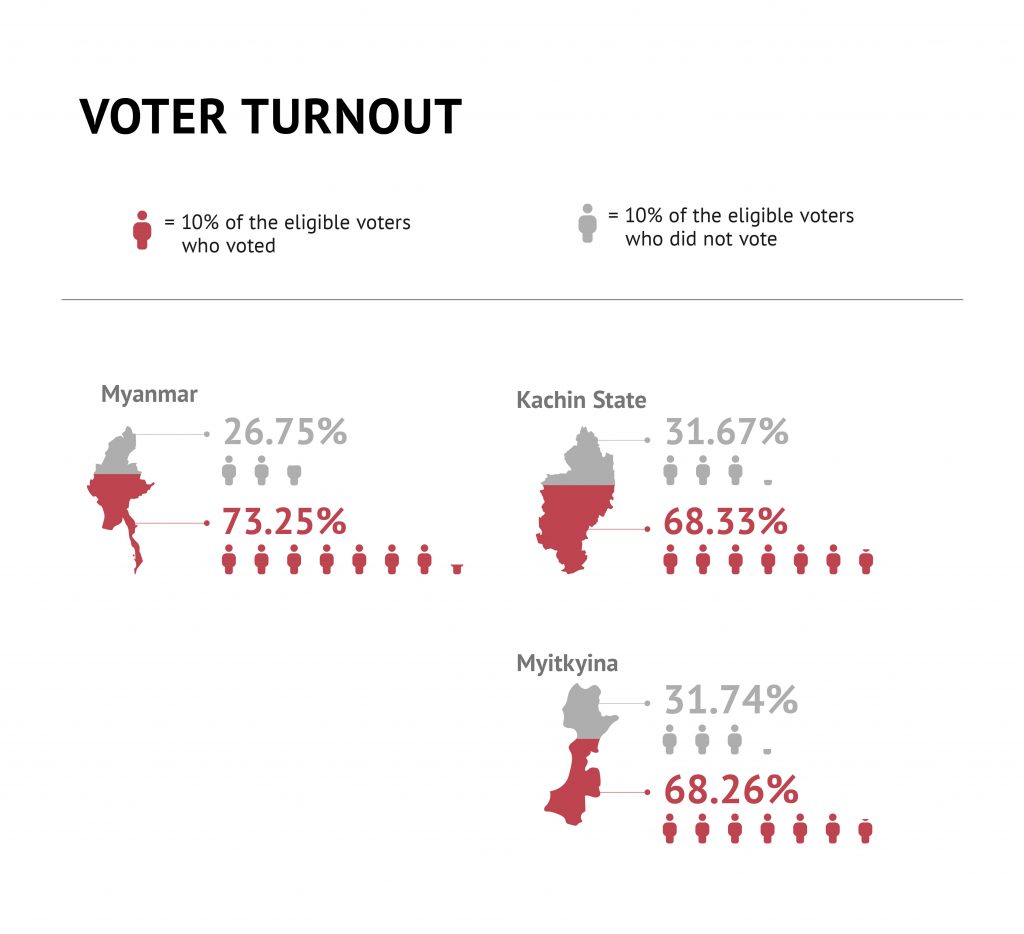

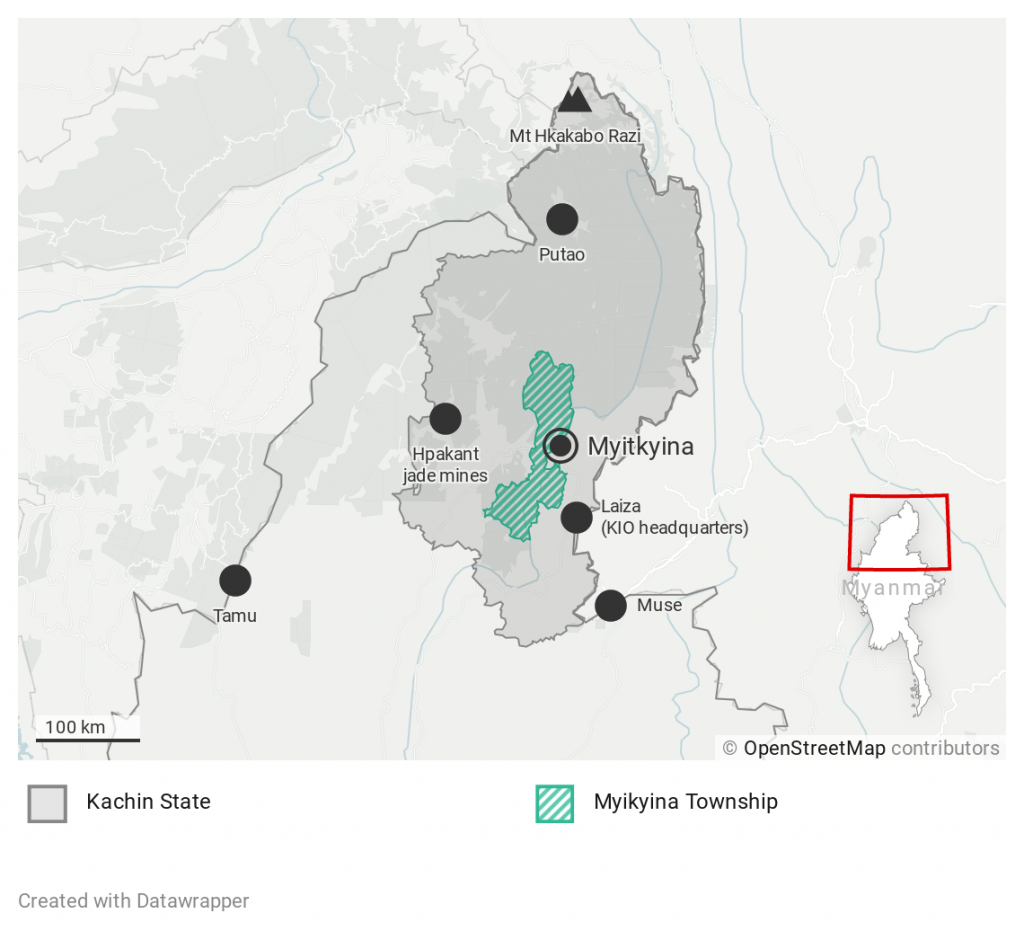

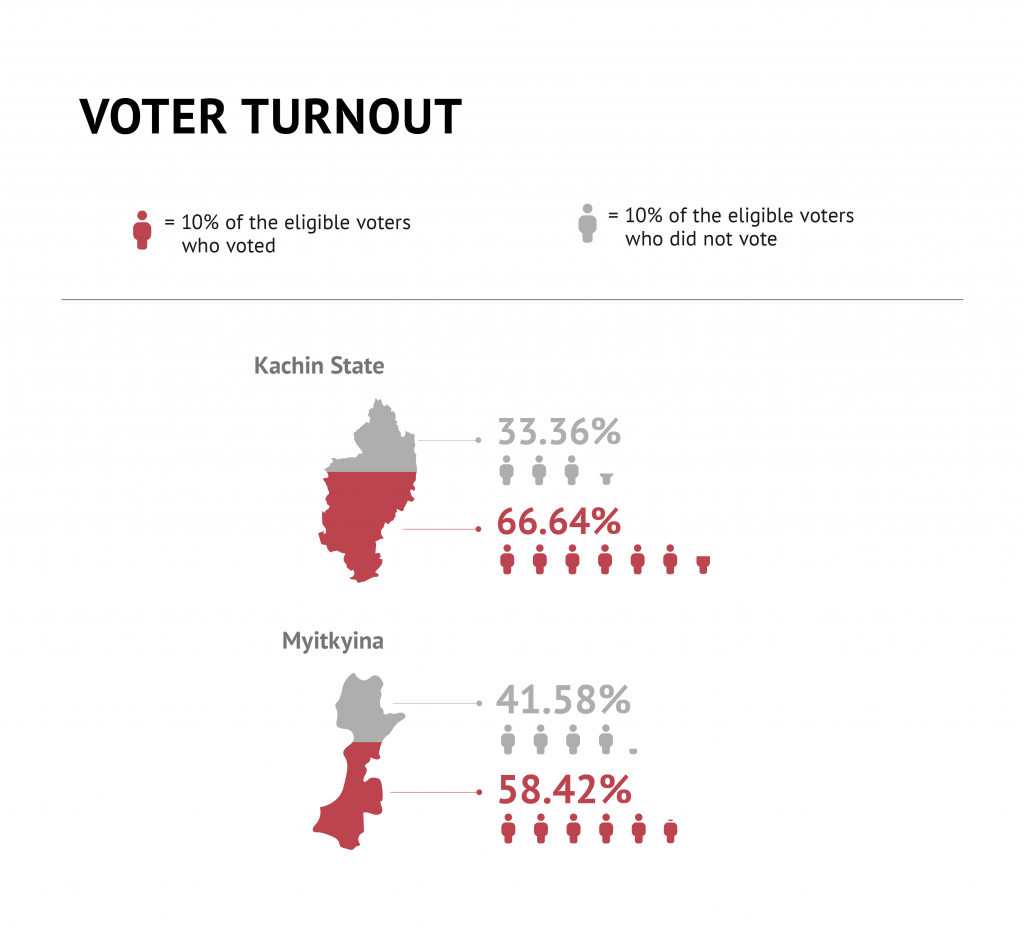

Election day went smoothly in Myitkyina, the Kachin State capital. As in much of Myanmar, the queues were long, even though turnout was well below the national average of about 70 percent. In the end, more than 58pc of eligible voters turned up to cast their ballots in Myitkyina. And, as in much of Myanmar, the National League for Democracy claimed a thumping victory, with almost 54pc of the total vote.

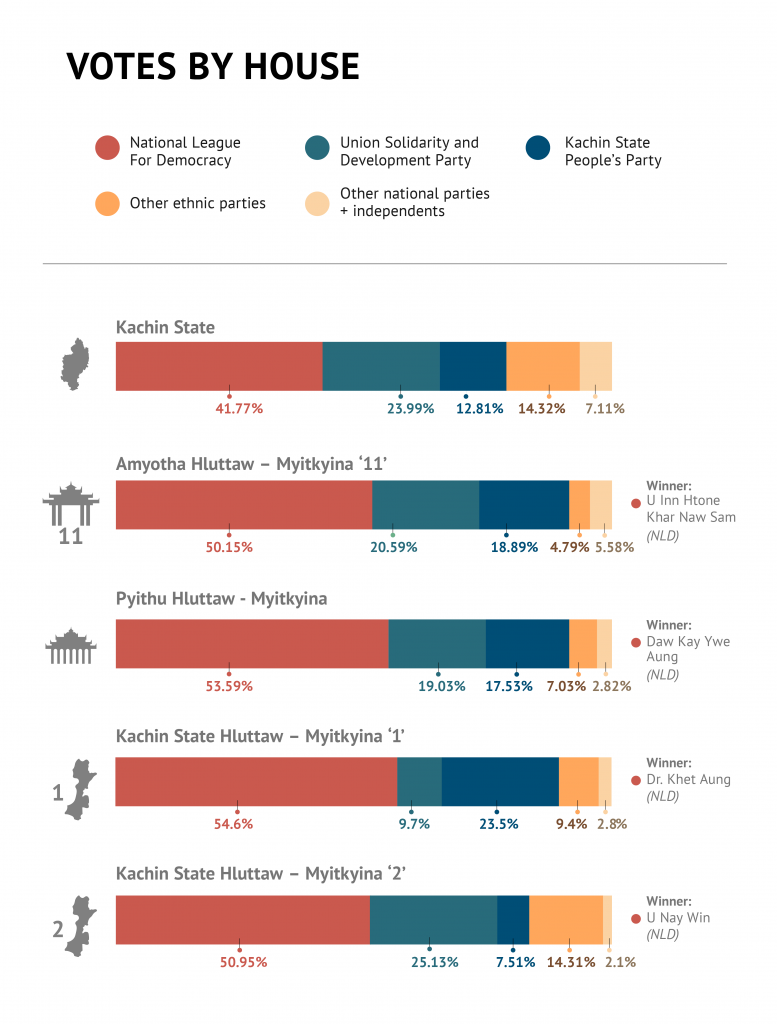

The party performed even better in Kachin that five years ago, defying expectations and dashing the hopes of what some believed to be an ascendant Kachin State People’s Party. Many ethnic groups in the state feel marginalised, and during the campaign voters told Frontier they had been unhappy with the NLD’s performance on economic development, the peace process and constitutional reform.

But on November 8, the NLD dominated the Pyithu and Amyotha hluttaw races, and claimed 28 of the 40 elected seats in the state hluttaw – up from 26 seats five years ago. Even after 13 military lawmakers are factored in, the party will have an absolute majority in the state parliament and be able to appoint the speaker and deputy speaker.

The KSPP, meanwhile, limped away with just three seats in the state assembly, and one in the Pyithu Hluttaw. In Myitkyina, it won only 17pc of the vote, behind both the NLD and the Union Solidarity and Development Party.

“I wasn’t certain of victory before the official results came out,” said the NLD’s Daw Kay Ywe Aung, who won the Pyithu Hluttaw race in Myitkyina. “The USDP is always a strong rival, and the KSPP had also gained popularity in the state.”

The appeal of party chair Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the advantages of incumbency, and the NLD’s closer engagement with constituents during a campaign period otherwise muted by COVID-19 restrictions seem to have propelled it to sweeping electoral successes in Kachin.

“We are isolated most of the time, and no political parties introduced themselves to us, but NLD members helped us register to vote, so my whole family voted for them,” said U Myint Htay, a banana plantation worker who moved to Myitkyina from Ayeyarwady Region’s Myaungmya Township six years ago.

Many KSPP candidates and members were left disappointed at their party’s performance. Formed by leaders of several ethnic Kachin parties in an attempt to present a united front to the public and avoid splitting the vote, the KSPP ended up doing no better than one of its predecessors, the Kachin State Democratic Party, which won three state hluttaw seats in 2015.

They blamed a host of different reasons for their poor showing, including COVID-19 campaign restrictions that limited them to gatherings of no more than 50 people.

Parties did organise some rallies in the first few weeks of October, but most were shut down and publicly criticised for potentially spreading COVID-19. This hindered newly-formed parties like the KSPP, who were still trying to get their name out, more than established parties like the NLD and the USDP.

“Our defeat is in a way a side effect of COVID-19,” Seng Nu Pan, the KSPP candidate for the Pyithu Hluttaw, said in an online conference organized by a party candidate after their losses.

At times, the search for answers within the KSPP has seemed more like a blame-shifting exercise. Some in the KSPP alleged the government and election commission had tilted the playing field in favour of the NLD, while others have blamed migrant workers – reasons that largely failed to chime with the dismal number of votes the party received.

“We won in constituencies where we were able to introduce ourselves to voters, and we lost where we could not,” KSPP vice-chair Doi Bu told Frontier on November 9. “While our campaigns were muted, the NLD was absolutely free to campaign and rally.”

KSPP vice chairman-2 Gum Grawng Awng Hkam told Eleven Media that his party lost because of votes from an influx of Bamar migrant workers who voted for the NLD. Migrant voting was made easier by a change to election by-laws earlier this year, which allowed people to transfer their vote to a constituency if they have lived there for at least 90 days – down from 180 days previously.

“We were defeated by votes from migrant workers … Otherwise, there was no reason we could not win,” Gum Grawng Awng Hkam said.

Even without COVID-19 restrictions, the KSPP and the several other ethnic parties representing the diverse array of communities in Mytikyina had fewer resources to campaign with than larger, more established parties.

“Our campaign budget didn’t allow us to campaign in more than 100 wards in Myitkyina,” Seng Nu Pan said.

The Lisu National Development Party’s resources were even more constrained.

“While candidates from other parties managed to hold four or five meetings a day, we were struggling to organise just a handful of people,” LNDP Pyithu Hluttaw candidate U Nee Sar told Frontier.

By contrast, the NLD used its wide network of support to organise meetings across constituencies. Ndung Hka Naw San, who won the Amyotha Hluttaw seat encompassing Myitkyina, told Frontier in October he was “attending five, six meetings of around 50 people a day in spacious compounds owned by party members”.

The NLD seems also to have convinced many voters that not voting for them would tilt the election toward the USDP, which might lead the country back to military rule, Doi Bu said. She said the NLD successfully portrayed ethnic parties as serving the interests of a single ethnic group, when they actually sought to represent entire states, in all their ethnic diversity – a claim that seems hard to square with the party’s post-election scapegoating of migrant workers living in Kachin. And although the KSPP seems to have gained significant support among Kachin youth, it clearly failed to attract much support outside of its own ethnic group.

Speaking before the election, Doi Bu also blamed this on COVID-19. “We’ve not been able to visit the areas where non-Kachin ethnic groups are concentrated. They’re fearful of COVID-19,” she said.

Besides the USDP disputing its losses in Hpakant, no serious complaints have been filed with the Kachin State election sub-commission, said U Htun Aung Khaing, its deputy director.

In Myitkyina, the USDP candidates have followed their losing party colleagues across the country in refusing to sign Form 19 confirming the outcome of the vote with the township sub-commission, but this is not required to certify the results. The party’s candidates have not returned repeated calls from Frontier.

While some KSPP members have described the campaign period and election process as unfair, it seems unlikely the party will file a formal complaint to the UEC, which would trigger a UEC-appointed tribunal with the power to overturn the result if there is evidence of cheating.

“Although the KSPP hasn’t won as many seats as expected,” KSPP chair Dr Manam Tuja told Radio Free Asia on November 13, “the vote is clean and we accept the result.”