There was some disagreement – but much debate and discussion – at the fourth installment of the festival in Mandalay last week.

By OLIVER SLOW | FRONTIER

INSIDE A conference room at a Mandalay hotel on November 4, a thanakha-clad girl clutching a bag of snacks attempted to unravel an earphone that had just been handed to her.

After grappling with the device for a few minutes, a slightly older girl next to her – perhaps her sister – untangled the cord and fastened the device to her ear.

Her face lit up as a Myanmar translation of Lonely Planet founder Tony Wheeler talking about his travels in the country in the 1970s and 80s came through the device. Recalling one trip through the country in 1983, Wheeler spoke of hiding under a blanket to pass a military checkpoint to get to Pyay (then Prome) and being forced to jump from a moving train at Bago (then Pegu) shortly after learning that it wouldn’t stop there.

The young girl was one of the hundreds of young Myanmar people who attended the fourth installment of the Irrawaddy Literary Festival, held at Mandalay Hill Resort from November 3 to 5.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

They came to hear dozens of speakers, both from Myanmar and abroad, talk about topics ranging from stories aboard pirate ships off the African coast, to assessments of the current political situation inside Myanmar.

This year’s event was not without controversy. Some international writers had chosen not to attend, reportedly as a protest against the Myanmar government’s handling of the crisis in Rakhine State. There was also tension about a perceived lack of communication between the Myanmar and international writers.

Speaking to Frontier by telephone on November 6, writer Ma Thida said she was frustrated that organisers had not sought to promote cooperation between local and foreign invitees.

“We are in the fourth year of this event, but there were not many panels that were a mix of Myanmar and international writers,” she said.

Panels that only included Myanmar writers were often unnamed, which did little to generate interest in the discussions.

“If international attendees know what the panel is about, they are more likely to go. If they don’t know who is talking, and what it’s about, they will not attend,” she said.

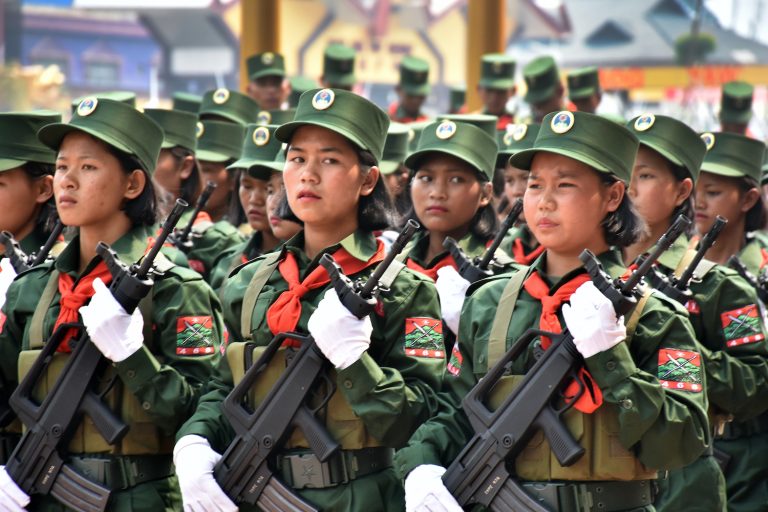

img_9268.jpg

An attendee at the Irrawaddy Literary Festival’s book market. (Kiira Gustafson | Frontier)

Speaking at the event’s closing ceremony on November 5, founder and festival director Ms Jane Heyn acknowledged that the event organisers “didn’t get everything right” but said that overall it had been a success.

In the event’s buildup, much coverage had been given to the fact that some writers had considered not attending the event as a protest against the situation in Rakhine State.

Many of the authors Frontier spoke to – including Wheeler, who in early October was reported to be considering a boycott – said they had decided to attend the event because it provided an opportunity to talk openly about the issue, and hear the views of people within the country.

The Rakhine crisis was discussed openly at the festival, coming up during many sessions.

At a discussion on November 12 to discuss her 2015 book The Rebel of Rangoon, journalist Ms Delphine Schrank, said that many people she had spoken to in Myanmar were in “denial” about what was happening in Rakhine.

Schrank’s book was based on research conducted as the Washington Post’s Myanmar correspondent when the country was ruled by the military junta.

She said that returning to the country for the first time in several years was “humbling” because many of the activists she had met in those years – the majority from the National League for Democracy – are still fighting the same bureaucratic apparatus they had been up against when the country was under direct military rule.

“In many ways, I think we’re asking the country to speed up quicker than it really can,” she told the audience.

Speaking alongside her, former diplomat Mr Giles FitzHerbert, said he had witnessed “an unwillingness for some people to recognise the scale of the atrocities we are seeing in Rakhine State”.

The festival also included a book market with dozens of stalls, with a smattering of English books among the many Myanmar language titles.

Among the sellers was U Htein Win, a photographer, writer and publisher who was selling his book 1974 – The U Thant Crisis, which features photographs he took of the student protests that year.

“At first, I wasn’t sure about attending, but it’s been a good opportunity to talk to people about the book, and for people to learn about what happened,” he said.

One of the event’s most popular forums was the November 4 screening of the film “We Were Kings”. It was only the second public screening of the documentary, after a showing in the United Kingdom in September.

The film chronicles the lives of the descendants of King Thibaw, who was ousted from the palace in Mandalay when Britain took control in 1885. It documents a debate within the family about whether now is the right time for the king’s body to be returned from India.

“It felt really appropriate to have the first [Myanmar] showing of the film in Mandalay – the home of the king, the last royal city,” the film’s director, Mr Alex Bescoby, told Frontier. “It was the first time showing it to a Myanmar audience, so it was an important test of what they would make of the film.

“The response has been amazing – exactly as we’d hoped. People have been very appreciative and very happy about it,” he said.

Speaking after the screening, Ko Zaw Myint, who lives inside the grounds of the palace where Thibaw once resided, said he had been aware of some of the story about King Thibaw, but not about the campaign to have the body returned.

“The film really taught me a lot,” he said. “I want to read more about it now.”

TOP PHOTO: Kiira Gustafson | Frontier