A weekend book market has served Yangon’s readers since 2017, but vendors say a slowdown in the economy and growing smartphone use have hit their sales hard.

By SU MYAT MON | FRONTIER

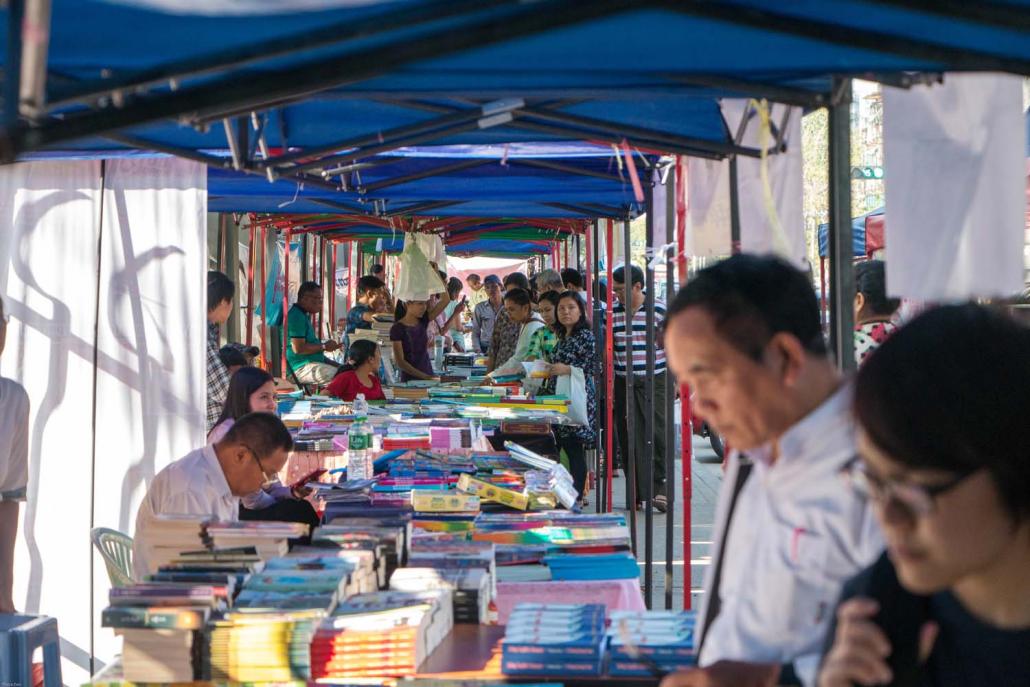

BUSINESS WAS brisk when the Yangon Book Street market, on Theinbyu Road between Anawrahta and Mahabandoola roads, was opened by the Ministry of Information and the Myanmar Publishers and Booksellers Association in January 2017.

The market has run only on Saturdays and Sundays and has not run at all during the rainy months each year between May and October, but it has provided booksellers with a prominent outdoor sales venue.

Stallholders said they enjoyed steady sales during the first year of the market, on the footpath outside the Secretariat building, downtown Yangon’s grandest landmark and the former seat of the British colonial government, now being renovated by a private consortium as a mixed public and commercial space.

Sales have fallen sharply since that first year, they said. On a Sunday afternoon in early March, only a few passersby were browsing the stalls, watched by hopeful vendors.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The downturn in sales began last year and has worsened since the start of this year, said stallholder “Insein” U Aung Soe, a 57-year-old writer who had served 18 years of a 58-year sentence for robbery when he was released from prison in January 2014.

Aung Soe sells books for children and adults, including four he has written himself, one being a memoir of his time behind bars and another about his experience in a labour camp constructing the Yangon-Mandalay Expressway.

Yangon Book Street opened as a weekend book market abutting the Secretariat complex in January 2017. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

In a January 2018 report by Frontier, Aung Soe claimed that U Aung Win Zaw – one of two men given death sentences for the assassination of revered lawyer U Ko Ni in Yangon airport in January 2017 – had previously approached him with a promise of tens of millions of kyat for doing the assassination, an offer he said he refused. In June 2017 he founded the organisation General Prisoners’ Rehabilitation Myanmar with other former inmates.

“The decline in sales is mainly because of the country’s economy,” Aung Soe said, alluding to a slowdown in growth since 2016 and a sharper downturn in business sentiment.

The slowdown in the economy was reflected in figures released in December by the World Bank, which forecast that growth would slow to 6.2 percent in 2018-2019, down from 6.8 percent in the previous year.

Aung Soe said that people who were struggling to make a living could not afford to buy books.

He said rising competition from other retail options was also squeezing his business. Booklovers now have an abundance of choices beyond Yangon’s archetypal street stalls and old street-level bookshops, including increasingly well-stocked supermarkets and a growing number of well-sponsored public events promoting literature.

Yangon Book Street. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

Declining sales have seen a sharp fall in the number of stalls each weekend at Yangon Book Street, which now line only one side of Theinbyu Road where they previously clogged both pavements.

Stallholders at the market pay daily rent of K5,000 to the MPBA. Aung Soe said he has asked for a reduction in the rent to help the stallholders survive and to support the important role that books play in educating the public.

Many stallholders are in the business because of their love for books, he said, rather than a hard-nosed interest in trade.

MPBA member Daw Tin Mar Oo said that when Yangon Book Street opened there were more than 150 stalls but the number had declined to about 80.

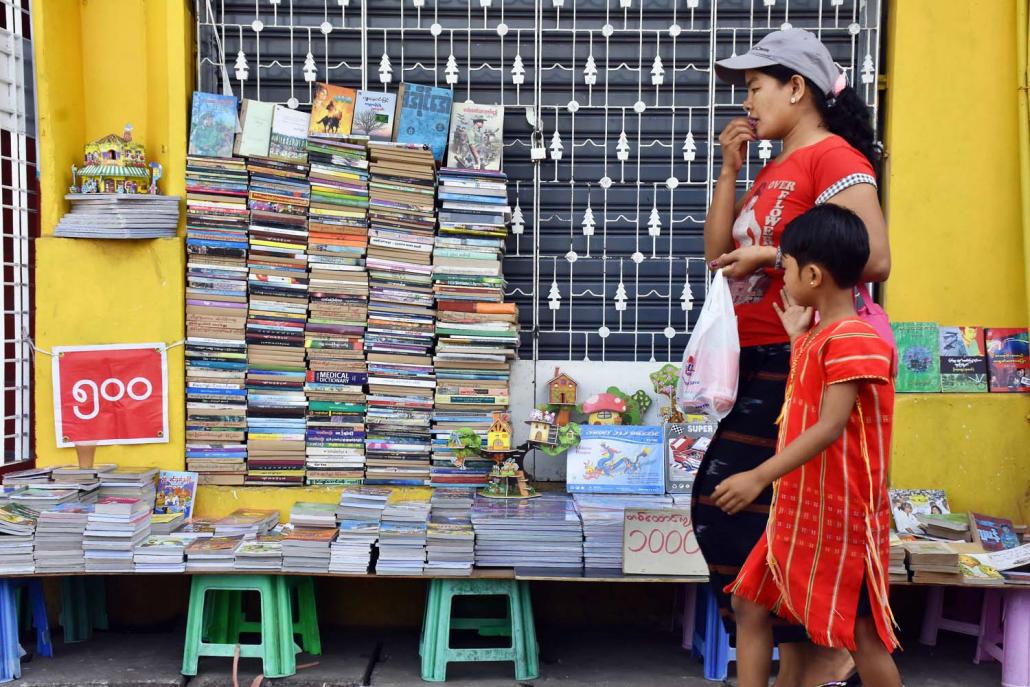

“The main reason is the economy,” she said, but added that fewer young people were reading books.

Tin Mar Oo said most customers at the market were in their 50s and 60s because there was a “reading gap” between the younger and older generations.

She said more needed to be done to promote an appreciation of literature among young people, many of whom were more interested in following social media on their mobile phones than reading books.

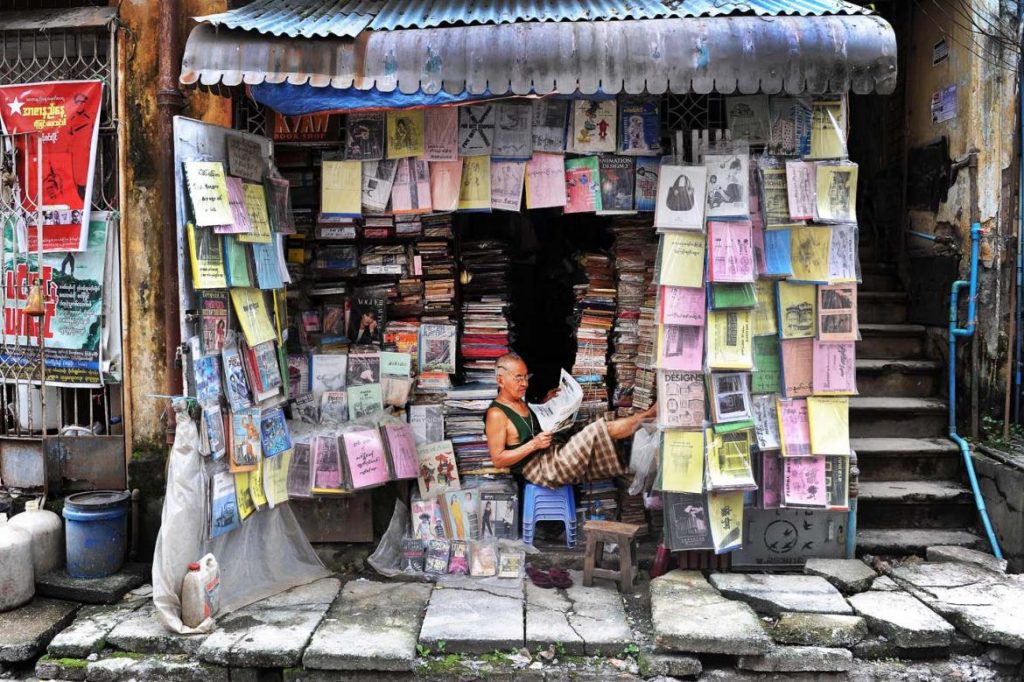

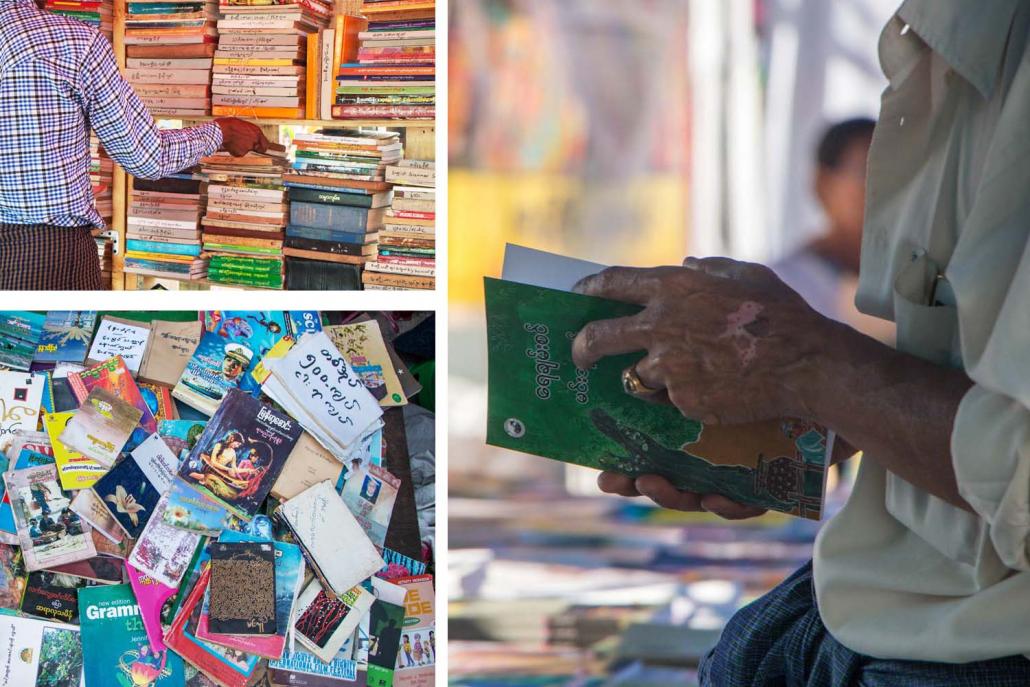

A streetside bookseller in downtown Yangon’s Kyauktada Township. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Online bookselling, though still small-scale in Myanmar, is also providing growing competition, including in the sale of old books, according to Tin Mar Oo, largely because of the convenience it provides customers.

Tin Mar Oo said she hoped the Ministry of Information or the Yangon Region government would one day create a permanent space with subsidised rents for vendors to support the book market.

“At the very least, there should be a dedicated venue for books, which would help develop [literary] culture,” she told Frontier.

Other booksellers in the downtown area also lament that the internet and smartphones are diverting the attention of readers.

They include U Tin Myint, 69, who still makes a living selling mostly old and second-hand books from a stall he opened on 37th Street in 1970.

His stall, which is open most days from 8am to 5pm, includes English classics such as George Orwell’s Burmese Days alongside Myanmar titles.

Sellers at Yangon Book Street hope for a more permanent venue to sell their books in. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

Tin Myint said although demand was still steady for old books, his overall earnings had declined, with smartphone use being largely to blame.

On a good day, Tin Myint can now expect to make up to K10,000, but many days he earns only half that.

“Saving money is hardly possible these days, but because I don’t have a family to keep, I can manage,” he told Frontier.

Most of his customers are older buyers who are mainly interested in history and old books, he said. It was rare to have young customers, he said.

Tin Myint however was confident there would always be a market for old books, despite the overall challenges facing the book trade.

“However, most importantly, a better place should be created for book selling,” he said, echoing calls for a permanent space for booksellers supported by the government.