After a decade of relative freedom, Myanmar’s military junta has turned back the clock by banning books, shutting down publishing houses and creating an atmosphere of fear that encourages self-censorship.

By FRONTIER

In 2007, well-known author Ko Wai Hmuu Thwin fulfilled a childhood dream by founding his own publishing house, called Roads of Yangon.

Established in Yangon’s Mingalar Taung Nyunt Township, the publishing house quickly drew a large following with its focus on politics.

Authors published by Roads of Yangon included prominent activist and political prisoner Min Ko Naing, 1988 protest leader and founder of the Democratic Party for a New Society Moe Thee Zun, and the deceased vice-chair of the National League for Democracy U Kyi Maung, a former colonel in the military.

Just three weeks after the military seized power in a coup, Wai Hmuu Thwin’s dream was crushed. On February 21, 2021, the regime forcibly shuttered his publishing house, accusing him of supporting anti-military resistance.

“I was very sad when I heard the news. There are no assault weapons in my publishing house, only books and articles,” said Wai Hmuu Thwin, who had gone into hiding after an arrest warrant was issued for Min Ko Naing a week earlier.

The military coup ousted the democratically elected NLD, plunging the country into a political crisis that has since blossomed into a civil war. Min Ko Naing emerged as a prominent figure in the resistance, helping to organise mass peaceful protests which the new junta cracked down on with lethal force, killing hundreds. He later went on to announce the formation of the National Unity Government, a rival administration appointed by elected lawmakers.

“The military started looking for me because they thought the publisher and the writer were related; from then on I had to run away from home,” he told Frontier on July 9.

“We had been planning to publish a book of poems by Min Ko Naing, but it had to be postponed because of the coup,” he added.

Roads to Yangon was one of the first publishing houses to be shut down. In the weeks after the coup, the junta focused most if its attention on independent media, arresting dozens of journalists and forcing the closure of most print media, although some independent publications continued to publish online.

After targeting news publications, the junta moved to stifle the literary sector and began revoking the licences of other publishing houses and closing book shops. In April 2021, the junta revoked publishing licences for Win Toe Aung Printing House and Yan Aung Library for publishing Lu Thay Lu Pyit, a controversial religious book. Written in 1958 by monk Shin Oakkahta, the book argued that human beings can only be reincarnated as human beings, not animals, a major deviation from traditional Buddhist belief.

Next was the Shwe Lab bookstore, which had its publishing licence revoked for printing a translation of My Possessive Step Bro, a novel about a homosexual relationship by author Hnaung A Yeik.

In May of this year, the junta shut down Lwin Oo bookstore in Yangon’s Hledan neighbourhood, after it produced a Myanmar translation of Dr Ronan Lee’s Myanmar’s Rohingya Genocide: Identity, History and Hate Speech.

The book, published shortly after the coup, documents the persecution of the Rohingya, a mostly Muslim minority group that in 2017 the military targeted with a brutal counter-insurgency campaign in northern Rakhine State. Thousands of Rohingya civilians were killed and hundreds of thousands more fled to Bangladesh.

While some in the international community labeled the military’s actions genocide, many in the NLD and broader pro-democracy movement defended the campaign. But since the coup, there has been some shift in public opinion, indicated by the fact that a publishing house translated Lee’s book in the first place, and the NUG has condemned the military’s violence and pledged to grant Rohingya citizenship.

Lee told Frontier that the banning of his book was an indication of “the lengths the junta will go to deny people in Myanmar access to … atrocities of groups like the Rohingya”.

Prior to the coup, Lee said, the “knee-jerk reaction” for many in Myanmar was to wholesale deny Rohingya atrocities. “They [the military] don’t want people joining the dots and seeing that if you let the military get away with persecuting one group, in very short order they will turn their guns on you.”

Self-censorship and defiance

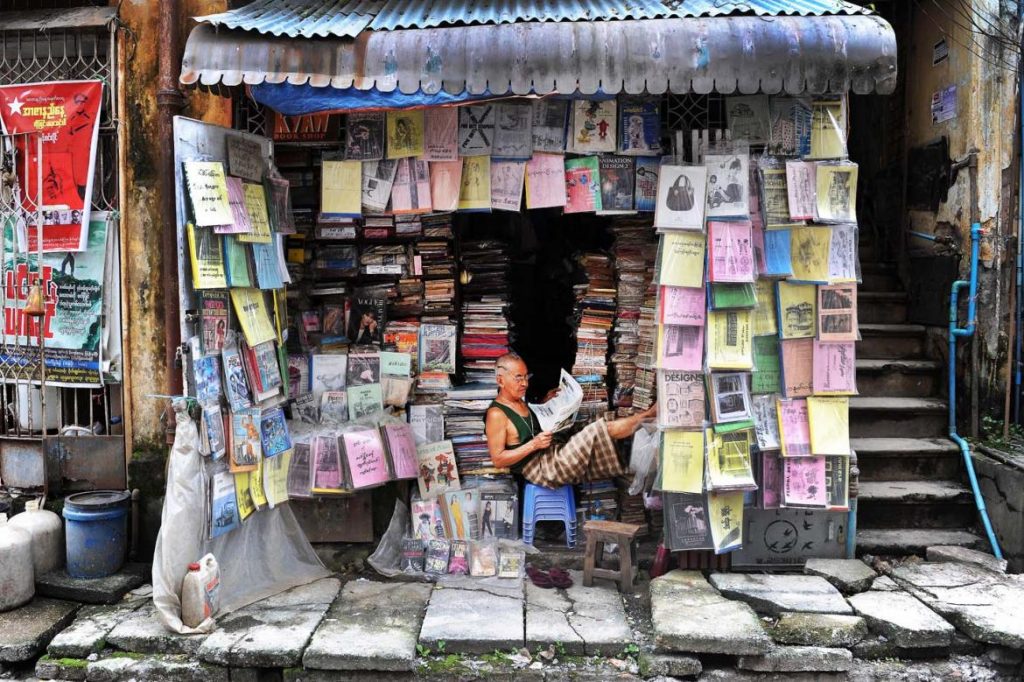

The suppression of the literary sector by a military regime is not new; it began with a suffocating pre-publication censorship system imposed by General Ne Win after he seized power in 1962. Many classic novels and poems, as well as works on politics, were banned.

“This system was a disaster for us; it closed people’s eyes and ears for many decades,” said Ko Maung Win*, a poet who owns a publishing house.

But in 2012, the quasi-civilian, military-backed government of U Thein Sein abolished pre-publication censorship.

Instead of approving books before publishing, censors only checked books after they were published, a reform that saw the emergence of new writers and a booming literary sector.

Around this time, writer and bookshop owner Ko Lin Wai* entered the publishing business. He said the post-censorship years were like a celebration for writers, but now the outlook for the industry was bleak.

“The literary sector is on a path to crisis. A storm is coming and we face rough times,” he said. “If the situation gets worse, it will be difficult for many publishing houses to survive.”

For translator and writer Ko Tun Lin*, the crackdown on the literary sector has meant two years’ work down the drain. In 2019 he began translating a book written by foreigners that explored the Tatmadaw’s involvement in politics and was due to be published this year.

“The book has more than 300 pages. I had permission to publish from the authors but after the coup the publisher said it was better to postpone publication. It was an unfortunate setback and my hopes began to fade,” Tun Lin said.

Tun Lin’s worst fears were realised in May when the military banned publication of the book.

“I’m very disappointed. I wanted to publish this book, but if it is published the [junta] is sure to take action. I can go into hiding but it’s not easy for the publisher to run away because he had many investments. He would suffer more than me if he was arrested,” Tun Lin said.

Publishers agreed that self-censorship has quickly returned to the industry. Wai Hmuu Thwin, whose colleagues have continued working while he is in hiding, said many have simply stopped releasing books about politics, even without being ordered to because they fear arrest.

“I’ve already cancelled the publication of 10 books,” he said. “Many publishers are concerned that the military will arrest them and send them to prison if they don’t like the content of a book. So, publishers do not dare to take risks.”

Wai Hmuu Thwin said publishers are in particular shying away from translations of books by foreign writers about Myanmar politics, and books written by prominent politicians. He said there was no possibility of publishing books about the resistance movement, widely known as the Spring Revolution.

“We can’t print anything about politics,” said Daw Hayman*, who has been in Yangon’s printing and book-binding business for more than 20 years. “We refuse to print them because if we did, we could face legal action by the [junta] and our printing equipment will be confiscated.”

Lin Wai, the writer and book shop owner, said many authors and poets wish they could write about the conflict, including its impact on those who have been displaced by fighting.

“Can we write about the conflict? Absolutely not. Freedom to write is under attack,” he said.

However, some groups have continued publishing underground at great risk. The University of Yangon Students’ Unionhas secretly distributed its Oway magazine in defiance of the junta. “Oway” is the Myanmar term for the chirping sound of a peacock, which is the symbol of student unions. The magazine was first published during the British colonial era.

“The magazine is being distributed in Yangon, Mandalay and Sagaing. We send it as a PDF file through social media to other members, who print and distribute it,” said a UYSU member.

Many members of the student union are in hiding or in prison as a result of their anti-coup activities. The activist said it was impossible to print the magazine at the printers they had used before the coup, so it was being produced by members using office printers in various locations.

“Producing the magazine is complicated. It takes a lot of work and we have to spend a lot of money. But it is the only way we can publish,” he added.

Financial crisis

As well as coming under pressure from the junta, book publishers also must contend with the economic collapse precipitated by the military power-grab. The paper used to publish books is imported, and publishers and printing house owners say prices have more than doubled since the coup largely due to the depreciation of the kyat.

“Previously, the price of a pack of wood-free paper was K41,000 [$22]. Now, it is more than K96,000,” said Lin Wai.

Publishers have been forced to increase book prices accordingly; Lin Wai said the price of most books at his shop had risen from K3,500 to K6,000.

“I didn’t want to raise prices, but I had no choice,” he said.

The increase in book prices at a time when the economy is in turmoil has led to a downturn in sales. Lin Wai said he was making about K15 million (over $8,100) every three months before the coup but earnings had since slumped to about K4 million (over $2,100) a quarter.

“People are struggling because of rising commodity prices, so rising book prices are affecting the market. It’s a problem we all face,” said Wai Hmuu Thwin.

These days, Daw Hayman has few customers. “Owners of small printing houses are struggling,” she said.

A book shop owner who requested anonymity said that if books aren’t selling and money isn’t circulating in the market, the industry will collapse.

“Paper prices are likely to rise further. If the situation gets worse, many publishing houses will close,” said the bookshop owner, who primarily sells novels.

Lin Wai worries that atmosphere of fear and the economic uncertainties will prevent the emergence of the next generation of writers.

“It will be more difficult for new writers if publishing houses do not publish because it is not commercially viable,” he said. “If publishers can’t publish, how can the authors have an income?”

Publishers said that although novels and monographs could theoretically be published online, the market for online publications in Myanmar was small.

Some, like writer-translator Tun Lin, have decided to publish online anyway.

“I love translating books on politics by foreign authors. Because of the military I cannot publish books, so I will publish online,” he said, adding that he knows he won’t earn much money. “It is more difficult to make a living from this profession.”

Wai Hmuu Thwin believes that the military will take further measures to restrict freedom of expression and to control the book publishing industry.

“They will try to restrict the people’s right to know. This is what always happens under military rule,” he said. “The people and the country are the biggest victims. The military is trying to take us all back into the Dark Ages.”

But Lee, author of Myanmar’s Rohingya Genocide, said the junta’s censorship campaign is a losing battle.

“The military can ban books but ultimately they can’t ban the truth and people will always be hungry for the truth,” he said.

* denotes the use of a pseudonym upon request for safety reasons.