A railway between Yangon and Pathein that was completed in 2015 but never officially opened is symptomatic of the expensive planning mistakes of the military junta and U Thein Sein government.

By KYAW YE LYNN | FRONTIER

Photos VICTORIA MILKO

WHEN LOCAL people don’t even know their town has a train station, something is very wrong.

But in a string of towns between Yangon and Pathein, it’s not unusual to get confused looks when you ask for directions.

“What? The train station? I don’t know,” a motorcycle rider told Frontier in the Ayeyarwady Region town of Pantanaw. “Are you sure? I don’t think our town has a station.”

Other residents gave similar responses before we eventually found one woman who was able to show us the way.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The tracks were just 100 metres or so from where we had been standing on the Yangon-Pathein Highway.

notrainsmilko-29.jpg

Locals in Set Kot dry paddy on the train platform. The line was completed in 2015 but never put into service. (Victoria Milko | Frontier)

The station itself is behind a government office, hidden from the public eye. Getting to it is difficult; the muddy pathway leading to the platform is covered in thick, waist-high bushes. Rusted railroad tracks are piled on each side of the path.

The station itself is a sorry sight, its windows broken and the water-damaged walls scrawled with graffiti. Vines have begun creeping up the walls, making their way towards the roof. The platform can barely be made out underneath the foliage.

The building is less than three years old. It has never seen a service, either passenger or freight.

“We just saw a locomotive running to test the line,” said Ko Khin Maung, a shop owner from Pantanaw. “We never saw a train again.”

notrainsmilko-7.jpg

The Ayeyarwady Bridge (Nyaungdon) is the centrepiece of the Yangon- Pathein railway but is already a white elephant, with no trains and very few cars on the road section. (Victoria Milko | Frontier)

It’s a similar story at Hlaing Tharyar Station, the Yangon terminus of the line. A road leads from the Yangon-Pathein Highway to a cavernous passenger hall and a 50-metre-long platform. Beside empty offices and silent ticket windows, a sign on the wall invites passengers to complain if they are overcharged for a ticket.

There are no passengers, though – just a family in charge of security and a large pack of dogs.

‘Wrong from the start’

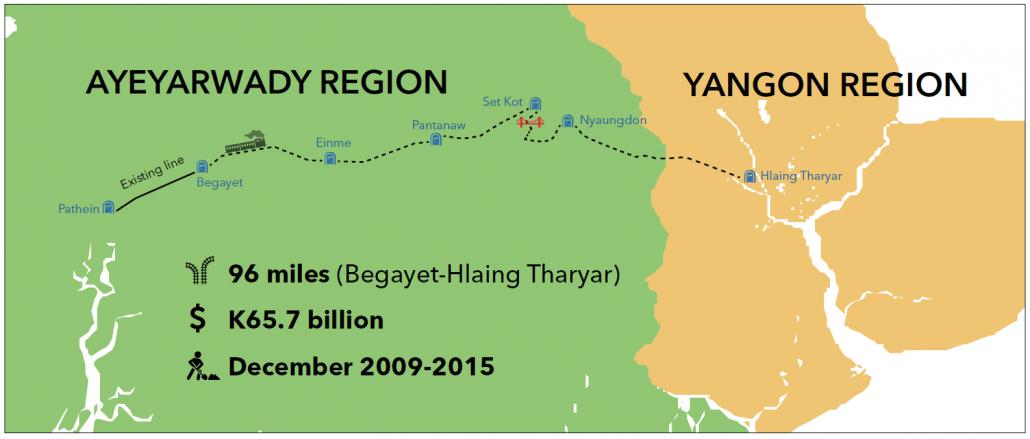

Myanma Railways began work on a 155-kilometre (96-mile) railway linking Yangon with an existing station at Begayet near Pathein in 2009-10, shortly before the military regime transferred power to the quasi-civilian government of U Thein Sein.

A January 2013 article in state-run newspaper Myanma Ahlin said the line was 50 percent complete and once finished would “guarantee better transportation” for both passengers and freight.

However, the planned completion date was pushed back to 2015 due to construction difficulties.

“It was a completely new line and we encountered some problems during construction due to sections of deep water,” said a manager at Myanma Railways’ Division 9, which is based in Hinthada.

railway-sidebar-2.jpg

“In some parts, the cost was estimated at K1 billion per mile,” he told Frontier on October 22. “In my opinion, the project was wrong from the start.”

Pyithu Hluttaw records from October 2014 state that the overall cost of the railroad was K65.777 billion, although this does not appear to include a bridge across the Ayeyarwady River.

Myanma Railways’ general manager for lower Myanmar, U Tun Aung Thin, said that by the time construction concluded up in 2015, Myanma Railways had realised there was not enough demand to cover even running costs, let alone the investment in the line. The project was officially “cancelled” before work even wrapped up; no official opening ceremony appears to have been held.

“No passenger or freight train has ever run on it,” Tun Aung Thin confirmed. “If we ran trains on the route we would definitely lose money … so cancelling before starting that route saved us from some losses.”

Bridge to nowhere

A rail line from Yangon to Pathein already existed before the generals embarked on their doomed project in 2009-10.

The line was one of the first to open, way back in 1903. From Pathein it arcs north through the delta to Hinthada, on the Ayeyarwady River, and then links up with the Yangon-Pyay line at Letpadan on in Bago Region. However, the lack of a rail bridge at Hinthada means a ferry crossing is required.

railway-sidebar-1.jpg

A major purpose of the Yangon-Pathein project was to fully integrate the rail network on the western side of the Ayeyarwady with the rest of the country through a bridge over the river.

The generals decided to build a new road and rail bridge across the Ayeyarwady at Nyaungdon, about 50 kilometres west of Hlaing Tharyar.

Ministry of Construction data shows the road section of the Ayeyarwady Bridge (Nyaungdon), including approaches, is 10,814 feet, while the railroad section is 20,545 feet.

It is one of five large bridges across the Ayeyarwady River that opened during the term of Thein Sein.

It is also a white elephant. Even the road section is redundant because it’s just a few kilometres upstream from the road-only Bo Myat Tun Bridge, which opened in 1999.

notrainsmilko-43.jpg

Built just a few years ago, Pantanaw train station lies abandoned. Few locals seem to know that it even exists. (Victoria Milko | Frontier)

When Frontier visited in October, there was barely a vehicle to be seen on the Ayeyarwady Bridge (Nyaungdon). Its main purpose seemed to be as a gathering point for local youths to take photos above the river.

The rail line has begun rusting, while some sections of the rail approach bridge have already fallen into disrepair.

The bridge was briefly used for about a year, when passenger trains ran between Hlaing Tharyar and Hinthada via Nyaungdon. However, the National League for Democracy cancelled the service in June 2016 because of a lack of passengers.

“It’s like an abandoned bridge,” said Dr Ohn Kyaw, a resident of Nyaungdon town. “It was built for railways but they just used it for a few months and then it was useless.”

“The former governments just wanted to make their men rich by giving them contracts for these projects,” he said. “No one [else] benefited from it.”

A colossal waste

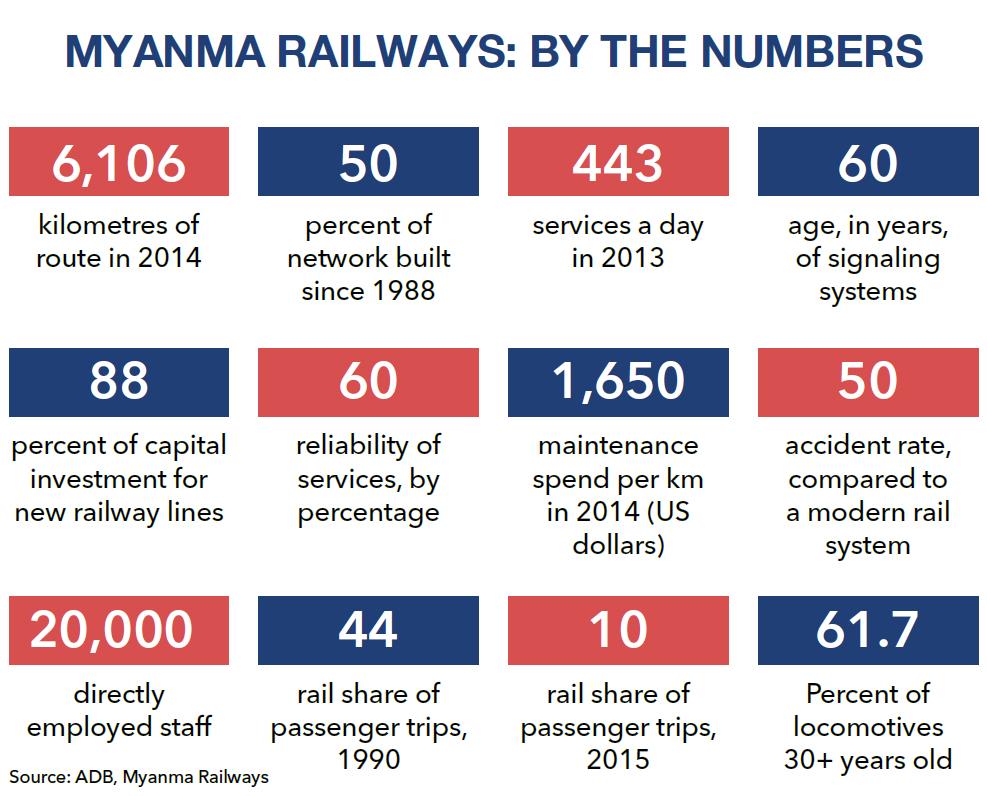

Officially Myanmar has the largest rail network in Southeast Asia, with more than 6,100 route kilometres (5,000 miles) in 2014.

About half of its network was built during the colonial period, starting with the Yangon-Pyay line in 1877 and including most of the country’s major routes, such as Yangon-Mandalay, Yangon-Mawlamyine and Mandalay-Myitkyina.

Just a handful of lines opened between 1930 and 1988, when the country had around 3,180km of route track. But when the military junta, the State Law and Order Restoration Council, took control in 1988, it embarked on a massive expansion. The Ministry of Transportation told the Pyithu Hluttaw last year that 3,480km (2,162 miles) had been added to the route map since 1988, including new lines deep into Shan State, Kayah State and Tanintharyi Region.

notrainsmilko-40.jpg

The dilapidated interior of Pantanaw station. (Victoria Milko | Frontier)

Sources in Myanma Railways said the expansion was to reinforce the military presence in frontier areas and support military campaigns against the country’s armed ethnic groups.

“They built these railroads without any consideration for the commercial viability,” said a general manager in railways enterprise. “They just wanted to have a way to quickly send troops and supplies to ethnic areas.

“So most of them were not sustainable, especially under the civilian-led governments.”

Others were built to link existing lines to industrial zones and state-run factories.

In the final years of the military junta a new wave of construction began, aimed at stretching the network as far as Sittwe in Rakhine State, Myeik in Tanintharyi Region and Kengtung in Shan State.

By this time, the minister in charge was U Aung Min, who would later lead peace negotiations and oversee the signing of the nationwide ceasefire agreement.

When Thein Sein took office, Aung Min initially remained in charge of the railways portfolio. The Myanma Railways official said Thein Sein and Aung Min could have saved many billions of kyat by suspending work on under-construction lines, including several major bridges.

“Many of the projects were just being started when power was transferred in 2011, but they decided to continue with them,” he said.

notrainsmilko-3.jpg

Hlaing Tharyar station has been closed since May 2016, when the NLD cancelled services to Hinthada. (Victoria Milko | Frontier)

During the Thein Sein government alone, hundreds of billions were spent expanding the network. According to the Asian Development Bank’s 2016 Myanmar Transport Sector Policy Note on railways, the government spent more than K620 billion on capital investment in rail between 2009 and 2014, of which 88 percent went into track – the majority new lines.

Daw Yin Minn Hlaing, a member of the Pyithu Hluttaw’s Transport, Communication and Construction Committee, told Frontier that she couldn’t understand why the Thein Sein government had continued the rail projects that had no hope of viability.

“I can’t imagine how many billions or even trillions of kyat have been wasted on these railway projects,” she said. “He should have known that it would only benefit corrupt officials.”

Reforming the railways

Policies since 1988 have been disastrous for Myanma Railways. By focusing almost exclusively on building new tracks, existing lines have been allowed to deteriorate and the network has grown too large to properly maintain. Tertiary lines, the majority built in the past two decades, now make up 58 percent of the route network but just 7 percent of overall traffic, the ADB note says.

It warned that Myanma Railways could “disappear” by 2025 unless action was taken to reform the state rail operator’s operations.

Under its “revival” strategy for Myanma Railways, ADB advocated a heavy rationalisation of services. It also recommended halting investment in new tertiary lines but maintaining capital investment at existing levels of around K100 billion and instead shifting it to rehabilitating existing track that is more heavily used.

The government has already heeded some of its advice. Within its first 100 days of taking office, the NLD shuttered 17 routes totaling 833km (518 miles) – a figure that does not include the Yangon-Pathein line, because it was never operational.

The Myanmar Times reported at the time that the lines had just 843 passengers a day and were generating just K205,000 in ticket sales, well below fuel costs of about K900,000.