Myanmar’s artists have celebrated greater freedom since censorship was abolished in 2012 and many have seized the opportunity to move beyond scenes of ‘tranquil beauty’.

By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER

Photos NYEIN SU WAI KYAW SOE

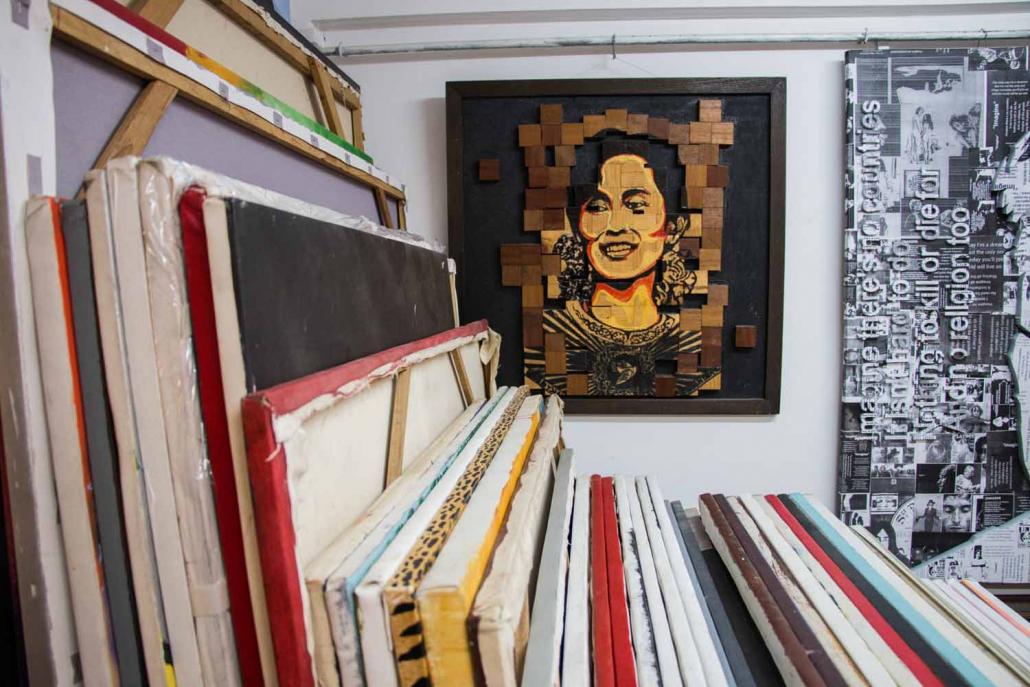

THE OIL, acrylic and mixed-media works on the walls of the Nawaday Tharlar Gallery have been carefully selected and displayed. The works in the attic, on the other hand, are piled on shelves or leaning against the walls in stacks dozens thick, leaving only a narrow aisle for browsing customers.

Fortunately, gallery owner Ko Pyay Way keeps them all catalogued on an iPad.

“Some of them cost less than US$100, but I have some collectors selling pieces here for $20,000,” said Pyay Way, whose gallery is on Yangon’s Yaw Min Gyi Street.

“If I say ‘yes’ to one [artist’s work], I have to say ‘yes’ to everyone because they are all my friends.”

nswks-44.jpg

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Ko Pyay Way inside his Nawaday Tharlar Gallery on Yangon’s Yaw Min Gyi Street. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier)

Pyay Way’s friends include artists, curators and buyers from every corner the industry, which after a half century of censorship and isolation is a patchwork of old masters and budding talent, tourists and serious collectors, storefronts in Bogyoke Market and high-end galleries selling works for tens of thousands of dollars.

“Myanmar art is not as diverse or exciting as contemporary art from some other emerging Asian countries, but now that the artists are unshackled from censorship and are joining the global art community this has definitely become a market to watch,” said Ms Gill Pattison, who founded River Gallery in downtown Yangon in 2006.

Although few connoisseurs would deny Myanmar its status as an exciting newcomer to the global art scene, the concept of “Myanmar art” is still a work-in-progress.

Missing movements

For decades Myanmar’s fine art scene languished under isolation and was stifled by a censorship regime as strict as it was fickle. Entire artistic movements passed it by.

“There was a very distinct boundary in terms of subject matter they could address,” Pattison said.

Abstract artist Aung Myint’s works were banned because they had too much red and black — the colours, the censors reckoned, of blood and evil. “Next” by painter Mor Mor, which won the Audience Choice prize at the 2008 Sovereign Art Awards in Hong Kong, cloaked political messages in the seemingly innocuous image of water droplets on a wall of peeling paint.

nswks-45.jpg

While the paintings on the walls at Nawaday Tharlar have been carefully selected, the gallery’s attic is full of canvasses leaning against walls and stacked in towering piles. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier)

“In public Mor Mor would say, ‘Oh, it’s just the beauty of nature’,” Pattison recalled. “But if you talk to her in private, she would say the decrepit wall is the state of the country and the droplets are tears.”

Formerly unthinkable works with political and other provocative themes have been appearing on gallery walls since pre-publication censorship ended in 2012. But the spectre of government disapproval continues to haunt studios and galleries, Pyay Way said.

In 2014, officials banned a painting by Pyay Way’s friend, Maung Thein Dhi; it was a minimalist nude that displayed nothing more scandalous than buttocks.

nswks-60.jpg

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier

“They said it looked very simple and took no effort,” Pyay Way said. “They thought, ‘This just wants to show nudity’.”

On the other hand, Aung Ko’s 2013 creation “Onward”, a life-sized sculpture of several nude men riding a trishaw, is one of River Gallery’s centrepieces. The nudity was very provocative, said Pattison, but the work symbolised Myanmar’s arduous effort to move forward as a nation.

Ironically, the same kind of clear political message might have spared Maung Thein Dhi’s nude, which was regarded as being pornographic. The case shows the strained and often paradoxical relationship between artists and the government. At least this time, though, no one went to prison.

Painting Myanmar

If Myanmar art gained anything under military rule, it was a unique aesthetic, a “tranquil beauty”, as Pattison described it.

“Contemporary art in other emerging nations is often not really about beauty at all. Art that is easily accessible and too pleasing is lambasted with the label of ‘decorative art’,” she said. “The Myanmar artists were not distracted into conceptual art because they had little exposure to it, and they were not distracted into political art because that was off limits to them. … Their main source of inspiration became what they see around them.”

Myanmar, at least, did not want for beauty, and Myanmar artists tapped into its wealth of natural, cultural and religious imagery. They learned to experiment with avant garde techniques in colour and form while making art that (for better or worse) simply looked good.

nswks-4.jpg

Aung Ko’s 2013 sculpture of nude men riding a trishaw is a centrepiece at River Gallery and symbolises Myanmar’s effort to move forward as a nation. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier)

The “Dancing in the Rain” series by Ni Po U shows women in traditional dress swirling and dancing in thick, vertical showers of gold, but the face of each woman is entirely black – a mask of stillness amid the electricity and life. The mastery of line, colour and composition is thoroughly modern, but the aesthetic is thoroughly Myanmar.

The “Myanmar Spring” series by Kyaw Nyo, 36, features swirling tongues of gold leaves on a fiery background. Kyaw Nyo studied realism at the University of Arts and Culture in Yangon, but soon abandoned the landscapes and still-lifes in favour of sweeping, iridescent abstracts that incorporate images of nature.

“I’m crazy about nature subjects,” Kyaw Nyo said. “I always use leaves typical to Myanmar.”

Kyaw Nyo usually sells his paintings for between US$1,000 and $3,000. He believes he could make much more money if he chose his subjects by popular demand, which would mean more traditional images, such as pagodas, ethnic minorities, flowers and monks.

nswks-38.jpg

Kaung Aung Paing is a restless experimenter whose oeuvre ranges from photorealistic still-lifes to cubism. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier)

Yet for Kyaw Nyo, if censorship led Myanmar artists to explore new ways of seeing its most beautiful images, it has also turned those images into its most enduring clichés.

Possibly the greatest of these are images of monks. They range from charcoal drawings peddled at Bogyoke Market to the works of famous painter Min Wae Aung of the New Treasure Art Gallery in Golden Valley, whose portraits of monks might fetch upwards of $20,000.

Self-taught artist Kaung Aung Paing, 49, painted portraits of monks until he was accused of mimicking Min Wae Aung. Kaung Aung Paing did not abandon images of monks, but experimented with new ways of presenting them. One series depicts them in black-and-white except for their alms bowls and the palm-leaf fans that cover their faces.

nswks-3.jpg

Work at River Gallery. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier)

“All artists draw [monks]. I wanted to highlight only the fan, the palm leaf, the bowl and the ribbon on the bowl,” he said.

As an artist, Kaung Aung Paing is a restless experimenter. His oeuvre includes photorealistic still-lifes, impressionism, abstract expressionism and cubism, to name a few.

“I make every kind of ‘-ism’,” he said. “Sometimes I’ll draw realism. Maybe I’m lazy, and I’ll do the abstract for a few pieces. I don’t want to draw more than three paintings in the same style. After three paintings I change.”

Foreign interest

The patrons of Myanmar art are as varied as its artists. Myanmar collectors typically want realist paintings of traditional subjects, such as the Shwedagon Pagoda or Bagan landscapes. Some seek works of the “Old Masters” who flourished before the Ne Win regime and others prefer contemporary offerings from established talent, such as artist and activist Htein Lin, who spent time as a political prisoner and then lived in Britain before returning in 2013.

Some Myanmar collectors, especially famous artists, are known for their lavish private collections. Others, Pyay Way said, stashed away huge caches of priceless works in the past because they were worried the military government might “request” they be donated to a state museum.

nswks-33.jpg

Gill Pattison inside River Gallery, which she founded in 2006. The gallery features works from many of the country’s top contemporary artists. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier)

Tourists, of course, make up a disproportionate share of Myanmar’s fine art buyers. River Gallery’s foreign patrons usually want something contemporary and interesting, but still essentially Myanmar, Pattison said.

“Visitors are often interested in the history and politics of Myanmar, so there is a segment that is attracted to works with a political element.”

Some foreign collectors are speculators trying to get in on the ground floor.

“They are buying a lot; they are buying art like snacks,” Pyay Way said. “The arts here, they didn’t get influence from other artists. They have their own unique style. That is something very serious collectors realised. They think Burmese art will change soon.”

nswks-15.jpg

Work at the River Gallery in Yangon. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe / Frontier)

They aren’t wrong, he added. Myanmar art is continually changing, and even its senior artists are still pushing boundaries. But in a way, the growing market threatens to slow the very innovation that has generated it. It is all too tempting for Myanmar artists to stick to the styles and subjects that made them famous rather than experiment.

Pyay Way’s friends, at least, resist the temptation.

“Honestly, many artists here could be making so much more money if they painted what people asked them to paint,” he said. “But they don’t want to go back.”