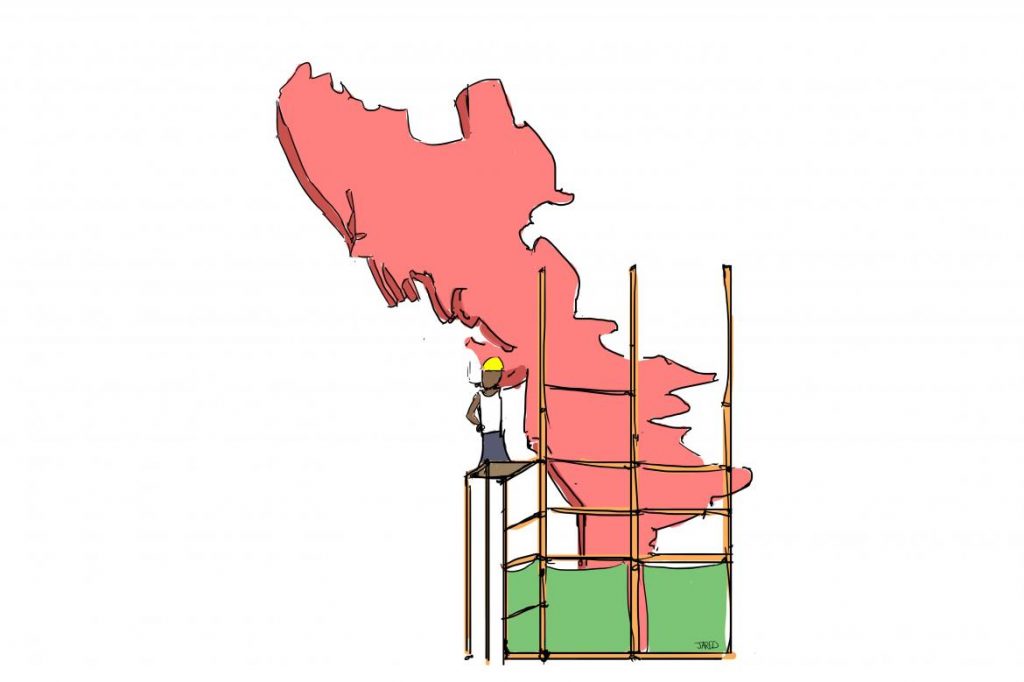

The Union government has announced a raft of development projects in Rakhine State in recent weeks.

They include building new bridges to improve road transport links between Sittwe, the capital, with the state’s impoverished north, as well as projects to provide residents with better access to electricity and telecommunications.

Along with building a camp that the government has said will provide temporary accommodation for verified returnees from Bangladesh, the authorities have made clear that they see development as key to solving the myriad challenges facing Rakhine.

Although development is of critical importance in Rakhine, one of the nation’s least developed regions with a poverty rate double the national figure, it is not the only issue needing more attention.

For this week’s cover story, Frontier travelled to Mrauk-U, capital of the ancient kingdom of Arakan and a great source of pride among the Rakhine. We went there with the aim of better understanding some of the grievances and frustrations that many Rakhine feel.

The international media is often accused in Myanmar of being biased in its coverage of the Rakhine crisis, by focusing too much on the plight of the Rohingya and ignoring the concerns of the Buddhist population.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Among the reasons for this is a government-enforced ban on independent media access to northern Rakhine, making it difficult for journalists to interview Buddhists affected by the violence and provide balance with accounts from refugees in Bangladesh.

Another reason is that the massive scale of the exodus is a story in its own right; the United Nations says more than 680,000 people have fled across the border since last August, while the number of Buddhists, Hindus and others displaced in northern Rakhine is in the tens of thousands, according to government figures. The harrowing stories of new arrivals in Bangladesh, and the huge challenges they are facing there, are helping to keep the plight of the Rohingya in the headlines.

It is also true that the views of the Rakhine, and other groups in the state, are often ignored, or worse, misconstrued. Almost six years since communal violence wracked the state, the Rakhine are still too often portrayed negatively or their opinions about the situation are over-simplified.

This is unfair because like all groups, there is a range of views among the Rakhine. As is well known, some hold extreme views about the state’s Muslim population – and Frontier heard them on its trip – but there are others who are sympathetic to the suffering of its Islamic community.

But the most common view we heard during our trip was that people want an end to conflict and an improvement in their standard of living after what they regard as decades of neglect by the junta and successive Union governments.

The trip, reported in detail in “The Lead” elsewhere in this issue, included visits to villages inhabited by Rohingya. All of those we interviewed said they had been confined to their villages since 2012 and that if they tried to leave, they would be jailed.

Frontier has given extensive coverage to the situation in Rakhine but it never gets easier to hear about the suffering and anxiety on all sides. The plight of the Rohingya is particularly harrowing. It is not easy to listen to a father tell of a child who has never known life outside his small village or be told about a women who died in pregnancy because she was unable to receive the most basic health care.

As the government continues to focus on bringing much-needed development to Rakhine, more needs to be done. Recommendation 18 in the final report of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State urges the government to ensure freedom of movement for all residents and says “all communities should have access to education, health, livelihood opportunities and basic services”.

The report acknowledged fear and anxiety in the Buddhist and Muslim communities and made five recommendations aimed at fostering inter-communal cohesion. The first called on the government to ensure that inter-communal dialogue was held at all levels of society.

The announcement on April 2 that Myanmar will allow a UN Security Council delegation to visit the country is an encouraging move but it is not yet clear if it will be given access to Rakhine State.

Unless the grievances of both the Buddhist and Muslim communities are taken into account, fear and distrust will continue to grow.