The latest foreign fiction and non-fiction once kept translators busy and appreciated in Myanmar but the golden age of revered translators has long passed.

By THI RI HAN | FRONTIER

There was a time in Myanmar when books translated from English were widely available, but their popularity has declined as a consequence of censorship under military rule.

Prominent translators in the past included Shwe Oo Daung, Thakin Ba Thaung, Dagon Shwe Hmyar, Tet Toe, Mya Than Tint and Maung Paw Htun. They were pioneers in literary translation who flourished in the 1950s and early 1960s.

However, after the Ne Win dictatorship seized power in 1962 it established the Press Scrutiny Board (renamed the Press Scrutiny and Registration Division in 2005), and the number of books translated from English went into decline.

Despite the decision by President U Thein Sein’s government in August 2012 to abolish pre-publication censorship, the translation sector has barely recovered.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Industry sources say a budding young generation of translators has emerged in recent years, but many remain weak in the quality and quantity of their work.

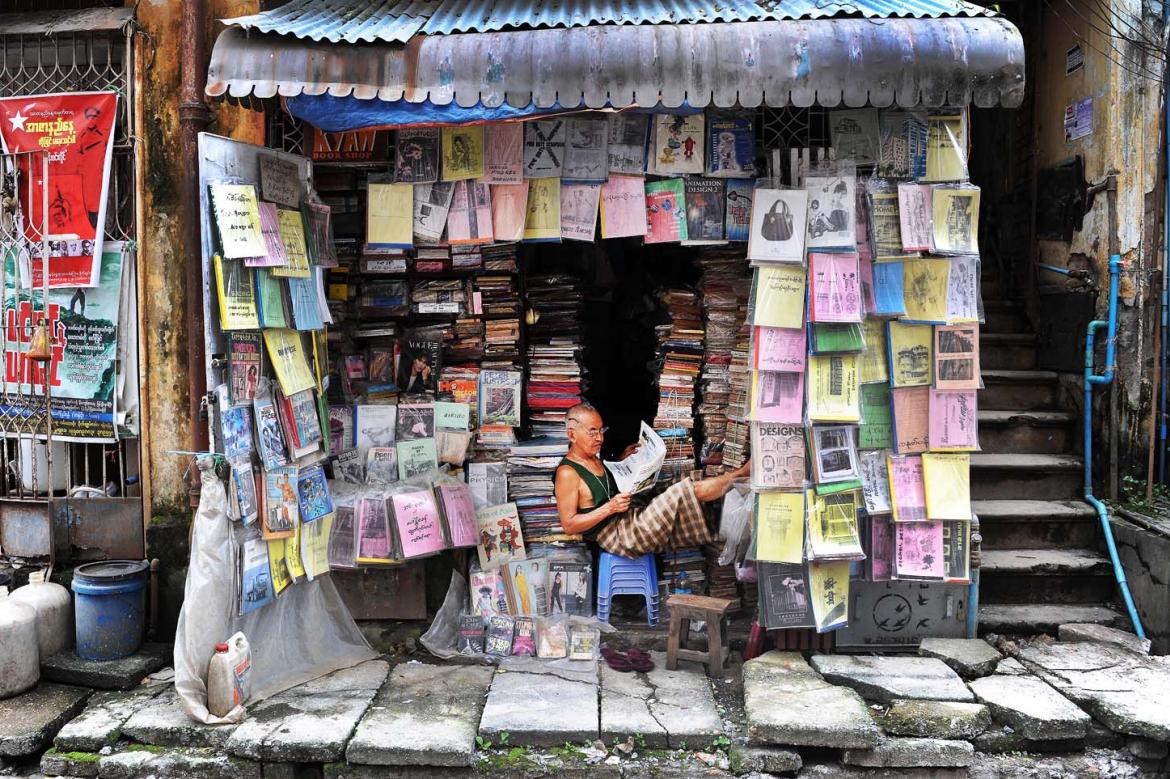

tzh_bookshop3.jpg

Experts blame Myanmar’s harsh censorship rules for the fall in the number of book translators in the country. (Teza Hlaing / Frontier)

U Aung Thura, a translator of books on philosophy and a publisher at Walie Society Publishing House in Yangon, said there were almost no translators who could translate books on philosophy from English.

“The slowdown in literary translation is mainly due to the PSB [Press Scrutiny Board],” said U Moe Thet Han, a translator of fiction.

“It’s been very bad, almost half of this book was censored, so it was not published,” he said, pointing to his translation of Norwegian Wood by acclaimed Japanese writer Haruki Murakami. “Indiscriminate censoring has made translators reluctant to do their job,” he said.

“PSB was unnecessarily very strict in the case of sex and politics, so there was a break in generations of translators,” said U Myae Hmon Lwin, writer and publisher at the Ngar Doh Sar Pay Publishing House in Yangon.

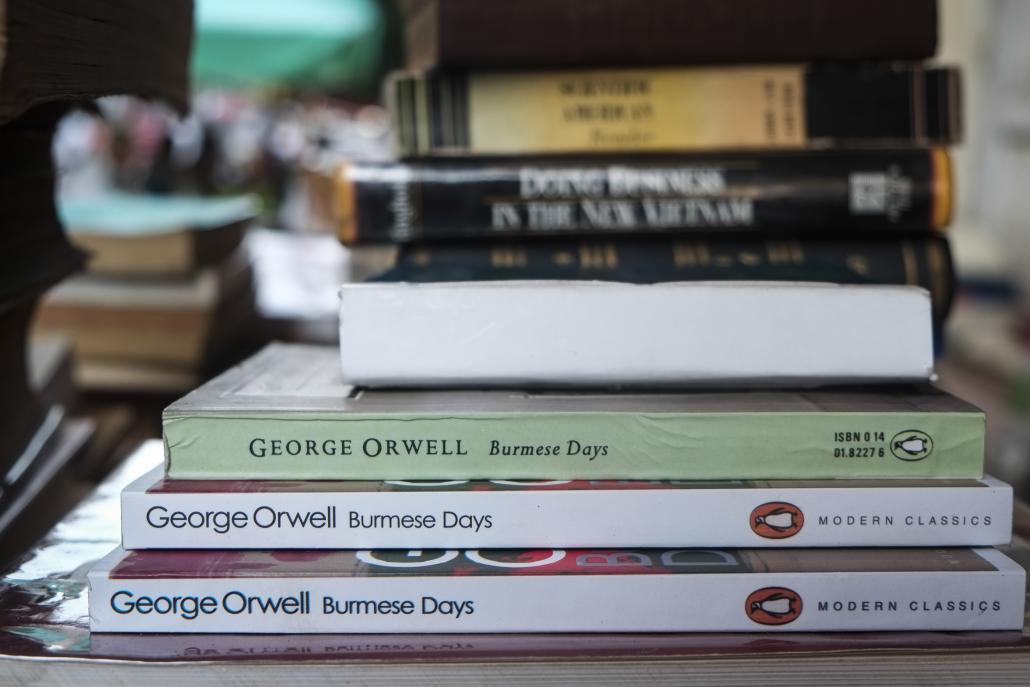

“In Myanmar, most translators translate from English into Myanmar, and there has been a considerable decline in the number of people who can read and understand English well due to the deterioration of the educational system. So the number of competent translators seems to have decreased,” said U Thurein Win, a translator of Burmese Days and other works by George Orwell, whose writing remains popular in Myanmar.

Myae Hmon Lwin agrees that Myanmar’s poor education system has contributed to the low number of translators.

“Myanmar’s poor education system has had a bad effect on Myanmar’s world of books,” Myae Hmon Lwin said. “It has made the people shun reading, rather than to make them love books. Without reforming the education system of learning by heart,” he said of the rote-learning in government schools, “it is difficult to improve this in Myanmar, [and] not only the translation sector”.

tzh_bookshop6.jpg

Teza Hlaing / Frontier

Spending on education in Myanmar is among the lowest in Southeast Asia, showed a survey released by NGO Action Aid Myanmar in March 2014.

“It is impossible to talk about creative thinking among young people, as most have been brought up in a faulty education system that discourages it,” said Aung Thura.

“Brought up by learning-by-heart education, when they come into a work atmosphere, they become robots who are unable to think creatively,” he said, adding that some religious and ethnic conflicts were the result of the poor education system. “Tied down by this dogma, they start to believe stereotypes and are unable to think and respond. It is very dangerous.”

The decline in demand for high-quality translations has meant that it is no longer possible to make a living from translation alone. Most translators work in the media sector, translating news reports from English to Myanmar and vice versa.

Aung Thura said it takes about three years to sell 500 copies of the books he’s translated.

In 1947, the year before the country’s independence, the Burma Translation Society (Sarpay Beikman) was established. Headed by incoming Prime Minister U Nu, the society was formed to translate foreign books on culture, literature and education for Myanmar readers. For 15 years until General Ne Win’s coup in 1962, the society published many informative books that were popular with readers of all ages. The quality of publications produced by the BTS deteriorated after it was nationalised in 1963.

“It would be good if the new government supports the reorganisation of the BTS again,” said Ko Phoe La.

Aung Thura said that as reforms continued in Myanmar, its world of literature should also change for the better.

“In Western countries, students still write after they have finished tertiary education and write when they come to work. But here in Myanmar, young people think they have nothing to do with writing after they have left university,” he said.