The routine infringement of copyright in Myanmar has devastated the literary world and other creative industries, and the violations will continue until laws aimed at protecting intellectual property are properly enforced.

By SITHU AUNG MYINT | FRONTIER

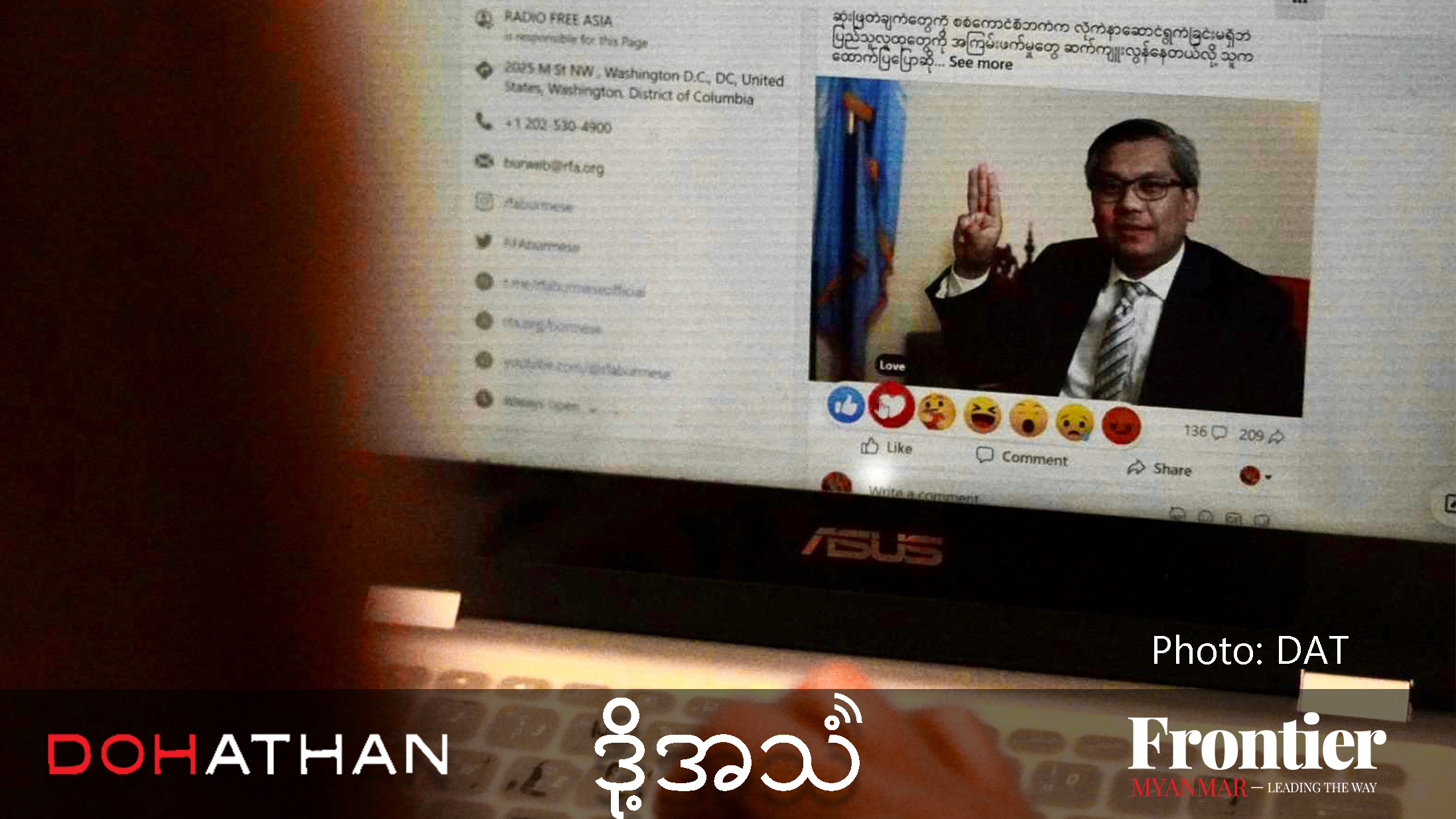

THE MYANMAR Publishers and Booksellers Association has again raised the issue of copyright protection, this time with an statement on July 18 seeking the removal of electronic versions of books that have been illegally posted on websites. The announcement listed 182 e-books that had been posted on websites without the permission of the writers or publishers, ready to be downloaded for a fee or free of charge. The association warned that if the files were not removed from the websites, it would seek prosecutions for breaches of copyright, including under the provisions of the Copyright Law enacted in May to replace the 1914 Copyright Act.

The abuse of literary and artistic copyright has long been a problem in Myanmar, and it’s questionable whether the statement will lead to the removal of e-books posted on the internet in violation of the law, or whether the new law itself will result in a significant reduction in copyright violations.

Before the internet was introduced to Myanmar in 2000, all literature was printed and disseminated by traditional publishers, but this situation largely prevailed even after the Kindle and other e-readers became popular in more developed countries in the late 2000s.

There was an attempt to create a domestic e-book market by the big media entertainment company Forever Group, which digitised the works of Myanmar writers for sale on the internet in the late 2000s. However, the venture was a commercial failure because internet connections at the time were poor, there were relatively few computers in the country and smart phones were far too expensive for most people.

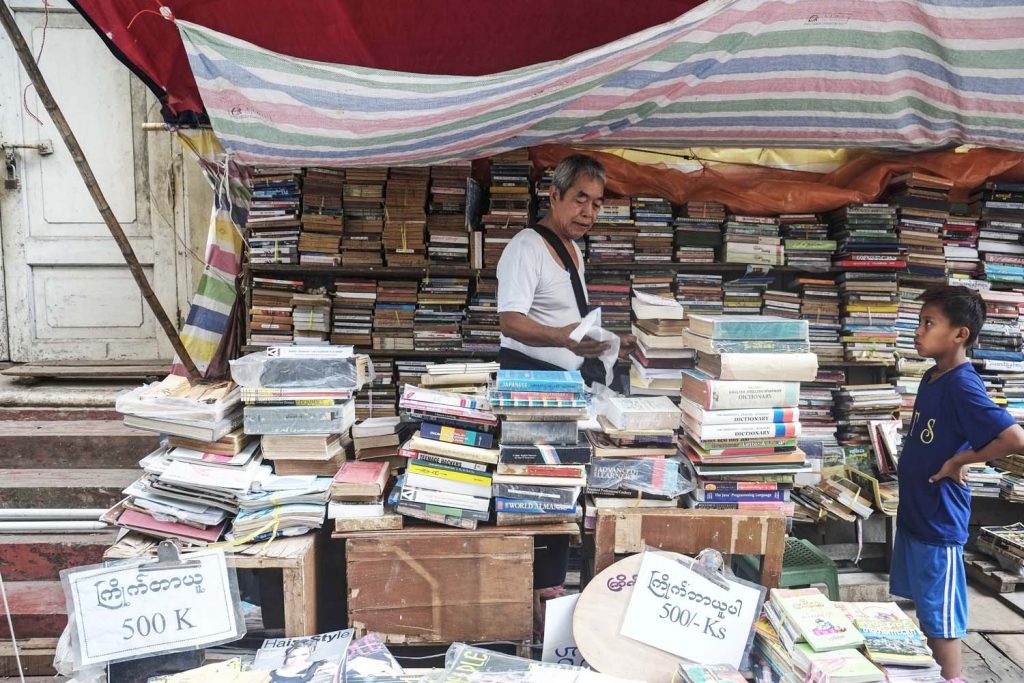

By the time the internet became widely available in Myanmar, thanks largely to the 2014 liberalisation of the telecommunications sector that brought the price of a SIM card down to an affordable level, there were so many publications available in cyberspace in breach of copyright that a legitimate e-book business would have been doomed. Some among the hundreds of websites that have digitised books have become so popular that they generate considerable income from advertising. Some have tens of thousands of books, including in the form of PDF files, which can be downloaded for free.

In its announcement, the publishers and booksellers association drew attention to, and commended, online businesses that have permission from writers and publishers to distribute publications for a fee. But these appear to be outnumbered by the book pirates.

It is not only the literary sector that has been affected by abuses of copyright. Movie lovers in Myanmar needn’t pay to watch movies in cinemas, or watch them via online streaming services, when they can take hard discs to shops that will copy high definition versions of foreign and Myanmar movies for a small fee.

Myanmar’s music industry has been seriously hobbled by copyright violations, which support a booming business in bootleg versions of songs and albums. Few consumers buy genuine productions when they can buy cheap copies from vendors or download them from the internet for free. The time when consumers were prepared to pay to listen to music has long gone. The victims of copyright abuses are the singers, songwriters, musicians and producers, who either struggle to make a living or have left the industry.

There are limits to what Myanmar can realistically do about people downloading copyright-infringing material from the internet, given how much of it is uploaded by people in other countries, but there is still much that could be done to punish bad actors in Myanmar. The successful implementation of copyright laws needed for Myanmar to meet international standards will require more than enacting legislation and warnings from professional associations. For one thing, it will require strict enforcement by a properly resourced and competent criminal justice system, which is not yet in place.