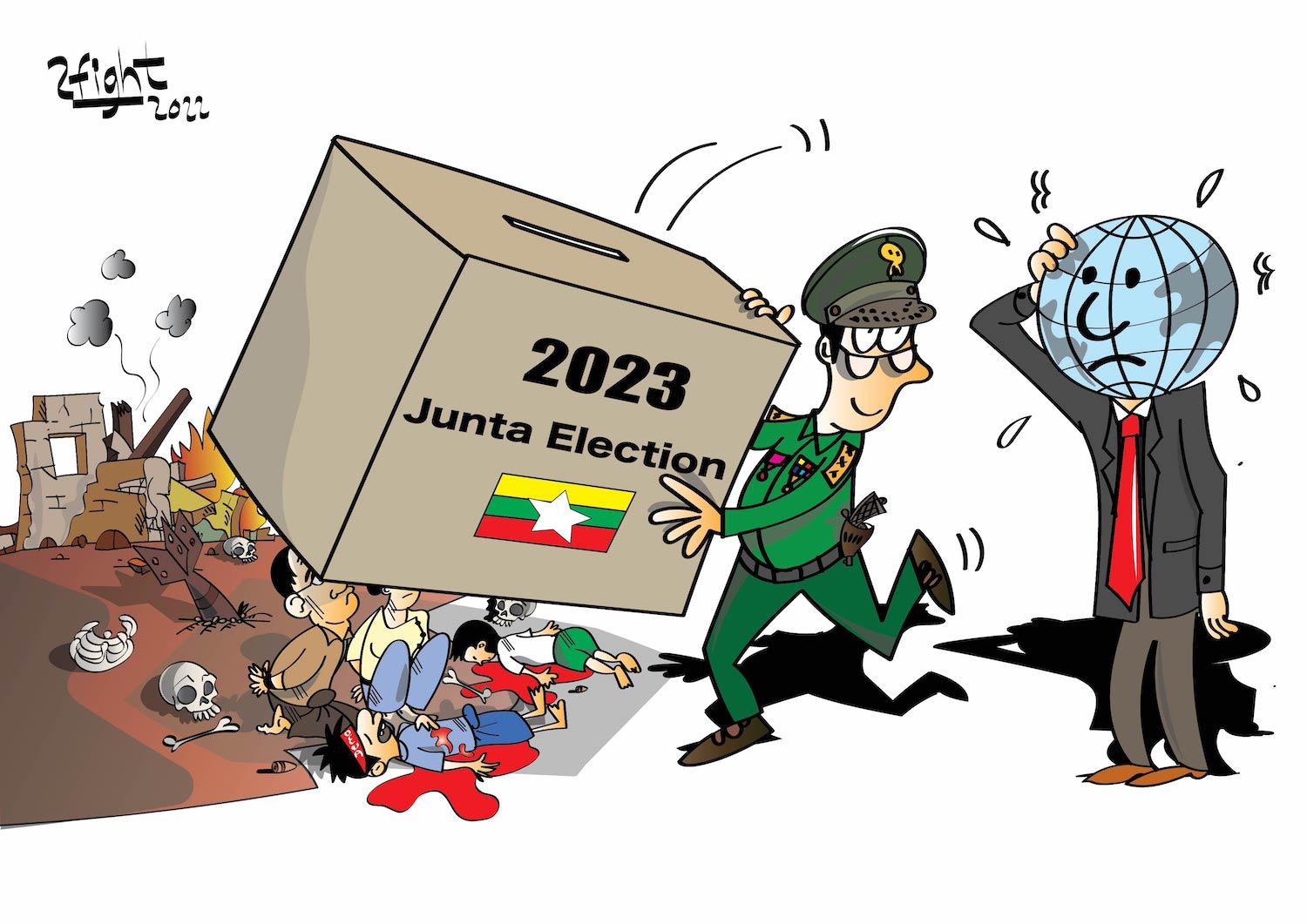

The Union Election Commission’s censoring of political party speeches underscores the need for Myanmar to unambiguously enshrine freedom of expression in law.

Let’s begin with some 2020 election trivia. What do the Democratic Party for a New Society, Arakan National Party, Chin National League for Democracy, United Nationalities Democracy Party, Arakan League for Democracy, National Democratic Force, People’s Party and Arakan Front Party all have in common?

That’s right: they’ve all had sections of their election speeches censored by the Union Election Commission. The list is likely to grow in the weeks ahead as the rest of the 90-plus political parties get their chance to present their policy platforms – or, rather, are denied the chance.

In July, the UEC issued a nine-point announcement banning content from party platform speeches that “undermine national unity and sovereignty”, “undermine rule of law” or fail to “respect” existing laws, including the 2008 Constitution. Speeches also must not damage or discredit the image of the state or the Tatmadaw, and must not “incite” members of the civil service “not to perform their duty or to oppose the government”.

It should be noted that censorship of election speeches isn’t new. Since the 2010 general election, parties seeking to present their platforms on state media have had to submit their speeches to the commission in advance for approval.

Comparisons with a decade ago are fraught because the context was so wildly different. The country was under a military regime intent on securing control of parliament, and everything was tightly controlled. The fact anyone besides the Union Solidarity and Development Party was allowed on state airwaves seemed a positive step, and parties embraced the opportunity regardless of the censorship.

In 2015, the UEC also issued an announcement regulating speeches on state media. In fact, the prohibitions in this year’s announcement are copied straight from the 2015 version. That year, though, the commission under former general U Tin Aye took a relatively light touch on party broadcasts – one of a number of things that helped to boost the credibility of the electoral process.

When this year’s rules were issued, Human Rights Watch called for the rules to be revised, pointing out that they violated international standards. However, at the time, there seemed little to be little cause for concern – because after all, the same rules had not caused significant problems in 2015.

Sadly, the current crop of commissioners seem to have less interest than Tin Aye in ensuring the November 8 election meets international standards.

The list of phrases that have been censored is long and, frankly, ridiculous. References to sections of the constitution and the military’s parliamentary bloc. Policy statements on broadening the tax base. Facts and figures on poverty. Calls for proportional representation. The terms “civil war” and “federalism”. For those who have worked under Ministry of Information censorship in the bad old days, this will all sound rather familiar.

The parties on the receiving end of this censorship have faced a tough decision: proceed with their speeches or abort the process entirely. Some – particularly those from Rakhine State, where campaign activities are largely impossible because of COVID-19 restrictions – have reasoned that they still need to take this important opportunity to reach voters.

The good news is that these attempts to stifle free expression are largely self-defeating. In reality, few people would have taken much notice, for example, if the Chin National League for Democracy had been given the chance to observe correctly that “the main factor of the civil war in Myanmar is that ethnic minorities feel that the Bamar majority are dominating them”. It’s a sentiment that is widely heard and read.

By choosing to boycott the process entirely, the Chin National League for Democracy, People’s Party and Democratic Party for a New Society, among others, have turned the tables on the UEC. The media coverage they have received due to the election commission’s censorship, and because of their principled stands against it, has outweighed whatever benefits they would have received from being given a freer rein on air.

It would be easy to pin this solely on the commissioners. After all, they are the ones calling the shots and have illustrated, once again, that they are out of touch with the political times.

But they are also just using the tools at their disposal. This is the risk Myanmar runs when it fails to unambiguously enshrine freedom of expression in law, and instead gives bodies like the UEC the power to censor political speech as they see fit.