An officer in the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army is in custody over a housing project in Myawaddy Township that has left several thousand people out of pocket.

By NAW BETTY HAN | FRONTIER

Photos NYEIN SU WAI KYAW SOE

WHEN THE Kayin State government evicted U Khin Maung Htwe from his new home in April, the state authorities resettled him on a bare plot on the far side of the same village, located in Myawaddy Township on the border with Thailand.

When Frontier visited Maekanae village on July 21, he was busy installing solar panels on a makeshift shelter roofed and walled with waterproof canvas. Because he was given little time to leave his former residence, he has had to rely on solar energy.

The state government demolished his home in the Shwe Mya Sandi housing project on the grounds that the land had been acquired illegally. Khin Maung Htwe, who is among several thousand people who have been evicted from the housing project for the same reason, said he was saving to build a new house because he would be able to settle permanently, and legally, at the new location – but only after buying the land from the state government. The price is a heavy discount from the market rate, but there is so far no word on compensation for the land he had paid for, and lost, in Shwe Mya Sandi.

“I was afraid it might happen again,” he said, referring to the risk of eviction, “but when the government said I would be given [official title] for the land, I was so happy.”

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

He seemed confident that the state government was a better guarantor than the man behind the Shwe Mya Sandi project – Major Saw Nyi Nyi, an officer in the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army, an ethnic Karen armed group that controls parts of Myawaddy, Hlaingbwe and Kawkareik townships, and which signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement with the government along with seven other ethnic armed groups in 2015.

A native of Magway Region in central Myanmar, Khin Maung Htwe heard about the housing project after he moved to work at Myawaddy town, a busy trading hub that sits across the Moei River from Mae Sot in Thailand. In reality, the project involved the sale of cheap land plots rather than the provision of pre-built housing.

“Some years after moving to Myawaddy, I heard that I could buy land cheaply [at Shwe Mya Sandi], so I sold up my farm [in Magway] and moved there three years ago,” he said. “But after two years my house was torn down.”

The house at Maekanae village of a resident relocated from the Shwe Mya Sandi housing project. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Nyi Nyi initiated the project using land granted by the government to the families of the DKBA as one of the preconditions for the armed group signing the NCA. However, the state government claimed that the housing project went on to exceed this concession and encroached on government-owned land, including a protected forest area.

The consequences also went beyond the demolition of houses and clearing of plots.

Kayin State Chief Minister Nang Khin Htwe Myint told Frontier that Nyi Nyi was arrested by the Tatmadaw on February 25 this year and after being questioned was handed over to be tried in a civilian court.

Speaking on August 20, the chief minister said the arrest was motivated by more than the illegal housing project: “I was told that he was arrested by the Tatmadaw, with which he had previously served, because he deserted from it before joining the DKBA.”

Nyi Nyi is being prosecuted by the government for a range of offences, including illegal land use and forging land ownership documents.

The leadership of the DKBA, meanwhile, has disavowed any role in the housing project, as well as the responsibility for paying back the people who bought plots. In a statement issued on March 5, the armed group claimed that it was a rogue initiative of Nyi Nyi.

The office in Maekanae village of the committee appointed by the Kayin State government to oversee the relocation of residents from Shwe Mya Sandi. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

The 5,000 plots

The Shwe Mya Sandi housing project was launched on 20 acres (almost nine hectares) in Maekanae village and the first 150 plots, measuring 40 feet by 60 feet (about 12 metres by 18 metres), went on sale in January 2017 for K150,000 each. Nyi Nyi sold the plots with receipts that bore the imprint of the DKBA and which described the K150,000 as a “donation”.

People who had bought the plots showed Frontier their receipts but asked that no pictures be taken of them out of fear of the DKBA. They claimed that their purchases came with land use rights for 11 years, after which the DKBA could reclaim the land, but this stipulation was not included on the receipts or any other documents that they were able to present.

By June 2017, about 5,000 plots had been sold and built on, say Maekanae’s original residents, who claim that some of their residential and farming land was taken for the project. Local people told Frontier that the cost of the plots was as much as 40 times lower than the market price for land in the area.

The original residents had written on January 13 that year to the state government’s committee for reviewing confiscated land to seek its help in resolving the situation.

On March 15, the Kayin government wrote to Nyi Nyi, instructing him to stop selling plots and to halt the building of houses, and on April 10, chief minister Khin Htwe Myint visited the housing project and warned those who had settled there that the government did not recognise their ownership of most of the plots.

But the sales and construction of houses by the new settlers continued. Tensions rose when, on June 6, more than 500 of the original residents demonstrated in Myawaddy town to demand the return of what they said was their land. This prompted a counter demonstration by more than 1,000 of the settlers, who feared being dispossessed.

Government officials returned to the settlement in July 2017 and reminded settlers that their plots had been illegally acquired and warned that the project would be halted. The settlers told the officials the government needed to discuss the situation with Nyi Nyi.

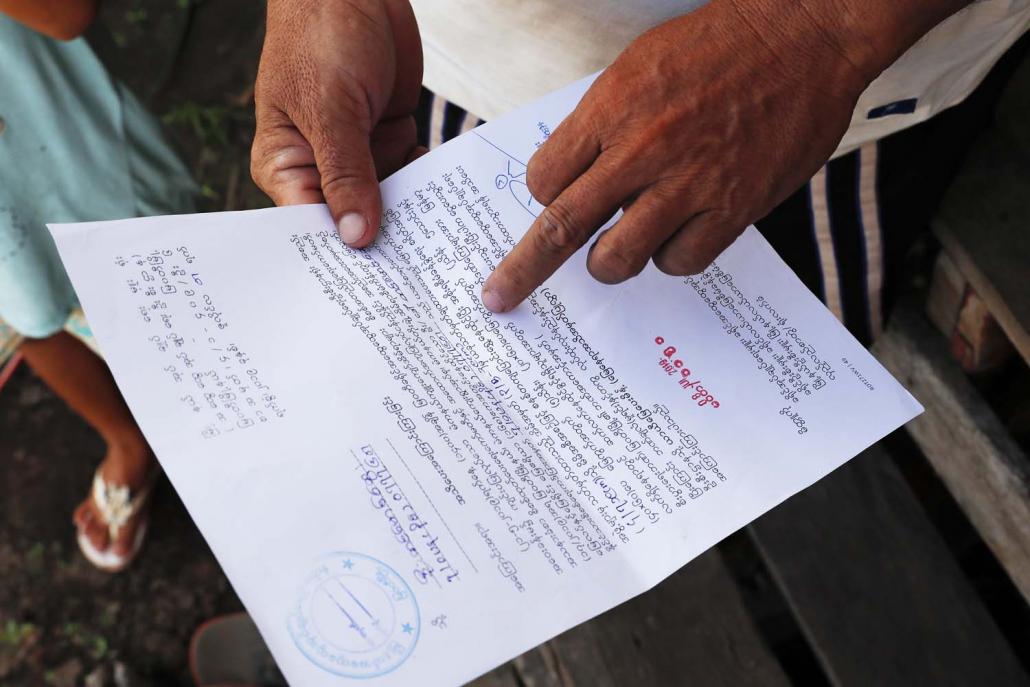

A letter from the Kayin State government showing the price for a plot of land sold to a resident relocated from Shwe Mya Sandi. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

‘Hurting us one more time’

In January this year, more than two years after the project was begun, the state authorities started demolishing houses. When Forest Department officials erected signboards warning that houses on its land must be removed, they were threatened by settlers and had to complete the task in cooperation with the state government, Forest Department spokesperson U Kyaw Myo Thu told Frontier.

The Kayin chief minister told Frontier that, during a visit to the site on March 5 this year, she told the settlers that the state government would resettle those whose houses had been demolished but they would have to pay the state government for their new plots. Despite appeals from the settlers, she gave no offers of monetary compensation for the destroyed houses or the sums they had paid to acquire land at Shwe Mya Sandi.

The chief minister told Frontier the settlers initially objected to paying for the new land plots because “they had already paid” for the plots from which they were being evicted, but she said they changed their minds after being told they would legally own the land on which they were resettled, and because this land would be sold “very cheap”.

When Frontier visited the Shwe Mya Sandi site in July, 1,000 houses and 4,290 plots had been demolished or cleared. According to a committee that includes MPs and community elders, which was established by the state government to oversee the relocation process, another 1,000 houses have been spared because they were built within the area granted by the government to the DKBA under the NCA.

The committee’s spokesperson, Kayin Hluttaw MP U Thant Zin Aung (National League for Democracy, Myawaddy-2), said it continues to receive demands for compensation, suggesting that not every settler had changed their mind in the way the chief minister described.

Thant Zin Aung said they were struggling to conclude the resettlement process before the deadline at the end of September for the settlers to pay for their new plots.

The relocation site for people displaced from Shwe Mya Sandi. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Daw Khin Aye Hla, who was resettled in March, said the General Administration Department had informed them of the prices in a letter dated July 1: K500,000 for a 40 foot by 60 foot plot, and K250,000 for land measuring 20 feet by 60 feet (6.09m by 18.2m). These prices are above those they had to pay for their plots in the Shwe Mya Sandi project but are still well below the market rate.

But though Khin Aye Hla welcomed the efforts the government had made to resettle them, she insisted that the arrangement was still unfair. “We paid money to the DKBA and now we have to pay the government. This is hurting us one more time,” she said.

There is also resentment among the area’s original residents that they had not been able to reclaim some of the land they said was taken for the housing project and that those being resettled had been able to acquire land cheaply.

Resident Saw Phoe Aye told Frontier the land used for project had been intended for “the families of DKBA soldiers after the DKBA signed the NCA”, and that “newcomers aiming to get land for a song should not be resettled so easily”.

Frontier was unable to confirm the whereabouts of the money received by Nyi Nyi for the Shwe Mya Sandi project, or whether he is able and prepared to pay it back

In a telephone interview on July 25, DKBA deputy commander-in-chief Colonel Saw Steel said the armed group could not take responsibility for a housing project in which it was not involved.

“The responsible person has been detained and I believe that the government has been systematically tackling the consequences,” he said.