A depletion in the variety of local food sources, stubborn poverty rates and stretched health services are driving high rates of malnutrition in the Ayeyarwady delta.

By KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

The crowd at the jetty in the Ayeyarwady Region town of Thabaung waited patiently for the boats that would ferry them to their villages on the vast flood plain on the eastern side of the Pathein River. Some had been working or shopping in the town – the administrative centre of a township of the same name – while others were returning from further afield, such as the regional capital, Pathein, about 30 kilometres downstream.

In an open area beside a trishaw stand at the jetty, a poor woman was making a catfish curry on a stove set up directly on the dusty ground. Her bawling 18-month-old son watched on, while her husband, a trishaw driver, sat nearby, plucking feathers from a crow he had shot with a catapult.

“This is our evening meal,” the woman said, pointing to the dirty frying pan. “We’ll cook the crow next.”

This was the scene that greeted Frontier on the first day of an assignment to investigate malnutrition in the fertile region spanning the Ayeyarwady River delta, the nation’s most important rice-producing area since British colonial times.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Figures from Save the Children show that Myanmar is among the 24 “high-burden” countries with the largest number of children under five years old who are moderately or severely stunted because of malnutrition. The nationwide prevalence of stunting is 35.1 percent, with wasting at 7.9 percent, including 2.1 percent with severe acute malnutrition, and 8.6 percent of newborns having low birth weight.

In Ayeyarwady, where the prevalence of stunting is among the highest of all the regions and states, one in three children are undernourished, according to figures from SUN CSA Myanmar.

SUN CSA Myanmar, which is part of a global movement active in countries with high numbers of children aged under five who are moderately or severely stunted, says six in every 10 children in Ayeyarwady are anaemic, meaning they lack enough healthy red blood cells for carrying oxygen and are easily fatigued as a result. SUN stands for Scaling Up Nutrition and CSA for Civil Society Alliance, and in Myanmar the group has 64 member organisations.

Early the next day, Frontier returned to the jetty for a two-hour boat trip to a village tract called Oke Shit. Near the jetty, a woman in her 60s was having a breakfast of rice and small fried fish and nothing else.

There are 394 villages in Thabaung Township, but only three wards in the town and four nearby villages – or less than two percent of the township – have electricity. The remaining villages rely on power from solar panels, most of which were installed by residents, though some were provided by international NGOs and the government.

After crossing the river, it was another 90 minutes by boat to Oke Shit, the main village in a tract of nine communities. The main village has a government secondary school and a rural health sub-centre that serves the entire village tract.

A woman eats breakfast at the jetty in Thabaung while she waits for a boat to take her to her village. (Kyaw Lin Htoon | Frontier)

U Khin Maung Myint, 49, a community leader at Oke Shit, said sources of protein from the surrounding waterways had plummeted, adding to difficulties in securing nutrition.

“When we were young, we could catch a lot of fish and shrimps in the creeks beside the villages, but now most of them have disappeared,” Khin Maung Myint told Frontier.

He said he was unsure of the reasons for the decline, but suspected it was because of a combination of fertiliser use, saltwater intrusion, increased flooding and hotter weather.

Most of Oke Shit’s 300 or so residents are of Bamar ethnicity but another village in the tract, Mi Chaung Kaik 1, which means “Biting Crocodile”, is home to about 600 Karen, most of whom are Christian. The health and resilience of these Karen villagers have also been hit by a decline in local sources of nutritious food.

U Gilbert, 66, an executive member of the Macedonia Baptist Church in the village, recalled when it was common for villagers to have their own vegetable gardens to supplement their diets.

“I remember that more than 20 years ago here, we were growing sunflowers, maize and chilli, but these crops were destroyed by mice, crickets and other insects,” he said.

Gilbert said it had also been common in the past for villagers to forage for edible plants growing in the wild, such as mushrooms, watercress, roselle and coriander, but such species were now rarely seen.

Across a stream from Mi Chaung Kaik 1 is the smaller Mi Chaung Kaik 2, which has a population of 169, also mostly ethnic Karen. Frontier found that even wealthier residents of the village were unaware of the importance of a balanced diet, suggesting that insufficient public education, as well as food resources, helps sustain malnutrition.

Among them was Naw Doh Aye Mu, 43. Her family farms 15 acres of paddy, making them better off than most in the village, but when Frontier asked what they had consumed over the previous 24 hours, the answer she gave was rice, fish paste, chilli salad and horseshoe leaf salad.

Food insecurity in Ayeyarwady, which makes it harder for residents to sustain balanced diets, appears to be driven by varied factors that include a shortage of farm labour, declining crop yields, inadequate financial and technical support from the government, and climate change.

Agriculture, on which the region’s economy also depends, is threatened by the intrusion of saltwater into inland waterways and apparent changes in climate, such as shorter and more intense monsoons.

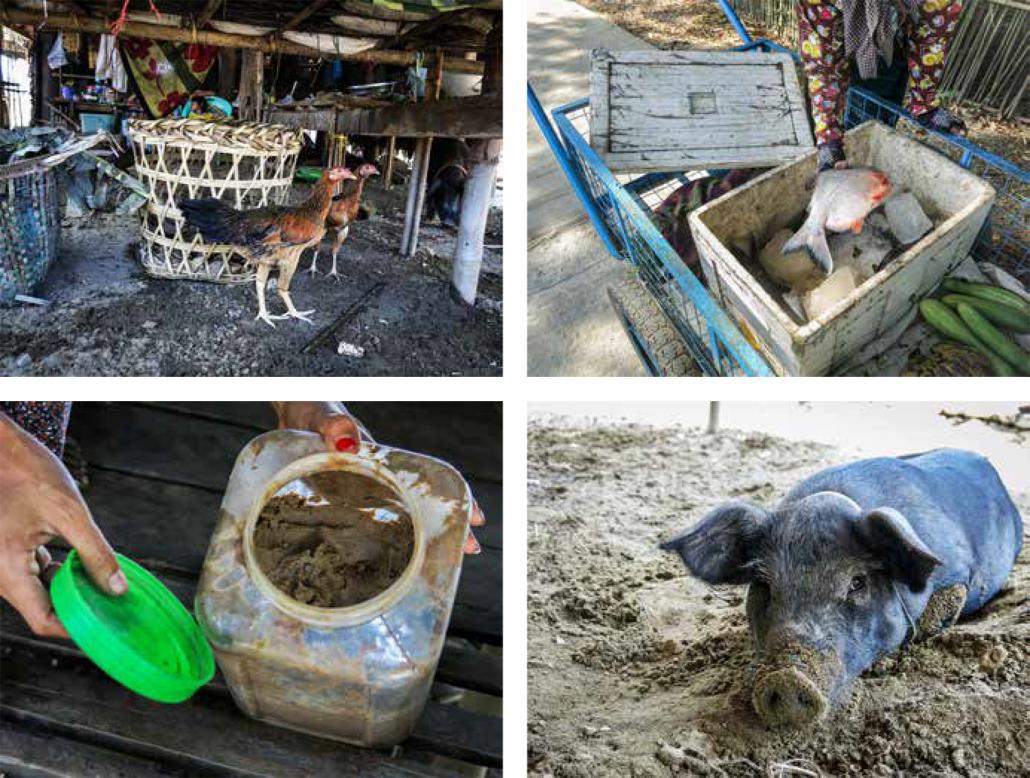

(Kyaw Lin Htoon | Frontier)

But it’s not just food that’s in short supply. When Frontier was researching this story in May, temperatures as high as 42 degrees Celsius were recorded in Pathein, Thabaung and Labutta and elsewhere in Ayeyarwady, up from previous years.

In Labutta Township, about 160 kilometres south of Thabaung by road, Frontier observed that residents of Ka Nyin Kone and Sin Chay Yar village tracts were struggling to get adequate drinking water, largely due to a lack of infrastructure and saltwater intrusion. Most have to spoon muddy water from depressions in dried up reservoirs and take the liquid home to filter in ceramic pots before it is consumed.

Flooding is also recurrent in the region, and some believe that climate change is making it more regular. In Thabaung, two-thirds of the township’s rural areas flood each year, and there was severe flooding in 2015 and 2016. The houses on the eastern side of Thabaung town are spared destruction by the tall stilts that they rest on, but the annual floods wreak havoc with livelihoods and impoverish diets.

The floods are usually at their highest from June to August, when many people rely on food supplies they have bought from earnings accumulated during the dry months.

“They store rice, fish paste and drinking water for the flood season,” said Ye Min Naing. “If you visit then you will see water everywhere, like an inland sea.”

The river water is now too brackish to drink, which is why villagers who can afford it store drinking water. But Oke Shit is lucky in at least one respect. A water purification machine was installed this year under a community development project that was launched in 2016 as a collaboration between the Department of Rural Development and the international NGO Mercy Corps.

The food and water challenges are compounded by a lack of health resources that mean when residents get sick, there are often few places to turn for help. Thabaung Township has only 10 rural health centres and 58 sub-centres, according to Ko Ye Min Naing, a project officer with World Vision, a Christian humanitarian organisation, which is involved in addressing malnutrition in the township. “But only a dozen of these 68 centres meet the standard requirements of the Ministry of Health and Sports,” he said.

Malnutrition is putting these thin resources under extra strain, he told Frontier. “People have little resistance to disease because of poor diets. If the healthcare system is not good enough, how can people protect themselves?” he said.

The health centres are not just underequipped, but also understaffed. Data from the General Administration Department shows that there are only five qualified doctors, 12 nurses and five health assistants for the entire township, which had a population of 154,400 when the last census was conducted in 2014 – one doctor for every 30,000 people.

Ye Min Naing said it was hard for the government to recruit medical staff for the area because few are prepared to work for long periods in remote rural locations. He has noticed since moving from Yangon to the township in 2016 that government medical staff rarely stay for longer than six months, after which they can apply for a transfer. Most are women who struggle with the living conditions and sometimes fear for their safety, he said.

Similar healthcare gaps persist across the delta. In Ka Nyin Kone village tract, residents waited two years for a new resident nurse to arrive to replace the one who resigned in 2017, according to the village tract’s former administrator and Ma Phyu Sin Win from local civil society organisation Swan Saung Shin.

A reduction in the resources needed for subsistence farming was also evident in Ka Nyin Kone, where narrow fingers of land reach into the sea. The tract of 14 villages has no police outpost and the cattle population has been depleted by years of rustling, making it harder for farmers to cultivate their land.

A fisherman carefully folds his net in Ka Nyin Kone village in Labutta Township. Catches in the area have been steadily declining, residents say. (Kyaw Lin Htoon | Frontier)

U Thaung Aye, 54, a community leader, said cattle were stolen every few months but no culprits have ever been caught.

He said that about 30 years ago most of the tract’s households had at least 10 cows or buffaloes, used for tilling fields and transport, but the total remaining population had dwindled to about a dozen.

Frontier compiled 24-hour diet records of five families chosen at random and found that the range of food was better than in Thabaung, but sources of protein were limited. Most families ate chicken or pork only about once every five to 10 days, depending on availability. While their fish intake might make up some of the shortfall in protein, often they were eating only fish paste or dried fish. Residents consumed little fruit, mostly mango and coconut.

“Fresh fish is best because the other products are processed with a lot of salt … a consequence of this is that people are more likely to suffer hypertension and other diseases,” said U Soe Nyi Nyi from the SUN CSA secretariat. “We encourage people to consume a variety of meats – not just fish, but also chicken, pork, goat and beef – because, of course people can get protein from all of them, but they have many different minerals and vitamins.”

Because local cows are put to work on rice fields, and there is a Buddhist taboo against slaughtering them, those wanting beef must take a 45-minutes boat journey to Labutta town.

Other food products are available in the tract’s two grocery shops. One of these shops, in Ka Nyin Kone village, is owned by U San Naing, 57, who resettled in the area with his family four years ago after returning from working in Taiwan.

As a young man, San Naing made a living from fishing in the creek beside the village.

“When I was about 20 we used to catch at least ten viss [16 kilogrammes] of freshwater prawns a day; but now if someone can catch two viss a day he’s regarded as a master fishermen,” he said, laughing.