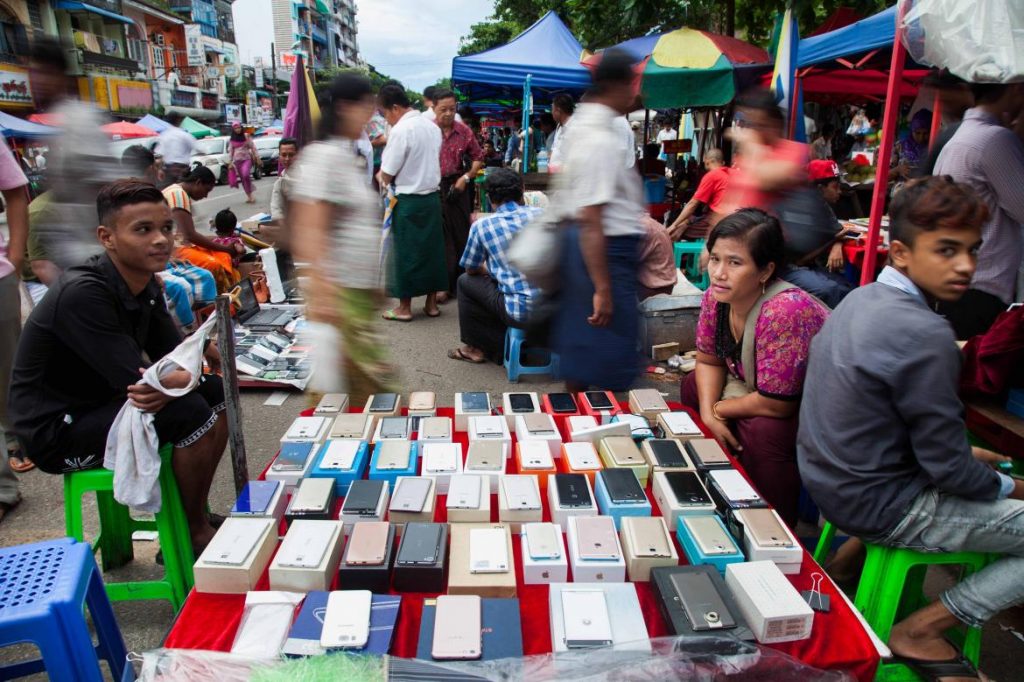

The competition for secondhand and counterfeit mobile phones is intense in a market that’s been flooded with the products since the telecoms sector was liberalised in 2013.

By THI RI HAN | FRONTIER

The stalls on the upper block of Shwe Bon Thar Street in downtown Yangon, crammed with mobile phones and accessories, open in the late afternoon to the shouts of vendors trying to attract the attention of passersby.

At one stall, a copy of an Apple iPhone 6 was priced at K100,000, much lower than about K1 million for a genuine model. Counterfeit handsets are known as clones and their appearance – if not performance – can be identical to genuine versions.

Although stalls selling mobile phones and accessories are common in big cities, they are relatively new in Myanmar. Until 2013 and the liberalisation of the telecommunications market, a SIM card cost upwards of K200,000 and sales were limited. The introduction of cheap SIM cards in 2013 transformed the market.

Ownership of hand phones has boomed since the telecoms industry was liberalised in 2013. (Theint Mon Soe – J / Frontier)

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

A 2015 report by Ericsson said Myanmar had 36 million mobile phone subscribers and was the fourth-fastest-growing market in the world.

“Some people use these handsets because they want to show off to their friends,” said Ko Phyoe Wai Soe, a project coordinator, as he browsed the counterfeit models on offer at Shwe Bon Thar Street. “Many can’t afford the original brand,” he said.

Secondhand models are more popular than counterfeits in Yangon’s booming phone market.

“I prefer secondhand phones because I can afford them and they work well; the originals are too expensive,” said Phyoe Wai Soe, holding a genuine Samsung handphone. He bought it from a friend for K22,000. A new model would cost K300,000, he said.

Theint Mon Soe – J / Frontier

Ko Pellay, the owner of Latha Lan Mobile, a shop that specialises in secondhand phones, said he opened the business in 2013 because of the boom in the telecommunications market.

“In the past there were not a lot of used handsets in the market, but when more became available, I opened a shop,” said Pellay. “Mainly we sell secondhand handsets but if a customer wants a new phone, we try to help,” he said.

There has also been a boom in websites, and social media pages, that specialise in selling secondhand phones.

Theint Mon Soe – J / Frontier

New smart phones are flooding the market in Myanmar. They have the latest applications and features and as more consumers upgrade their mobile phones for the latest models the result is more secondhand phones on the market.

“Often people cannot afford the genuine version of the phones they want, so when they are available cheaper as secondhand versions, they are happy about that,” said Pellay.

A challenge for businesses that buy and sell secondhand phones is stolen property.

“This happens every so often,” said Pellay, referring to the “thieves” who sell stolen phones. “Sometimes police come and seize the stolen phones and we have to go to court to testify. In these cases, we lose the items that we paid for,” he said.

Pellay has taken precautions against buying stolen phones, including requiring any customer wanting to sell a handset to provide proof of ownership.

“Firstly I ask anyone selling a handset for a voucher proving they own it. If they’re a thief, they don’t own the voucher. So if they can’t produce the document then I call the police,” he said.

Theint Mon Soe – J / Frontier

Intense competition has begun taking a toll on the surge in mobile phone shops that opened at the beginning of the telecommunications boom and many outlets are closing down.

In 2001, Ko Tin Htut Aung opened branches of his Araindamar phone shops in Yangon’s Insein and Tarmwe townships and in Mandalay. He had little competition for 12 years but that changed in 2013 when cheap SIM cards became available and it seemed as if mobile phone shops were opening on every street.

Tin Htut Aung decided he needed a change of business. He now runs a pet shop.

“People think that phone shops are an easy business, but they are not,” he told Frontier.

“There is a lot of competition and new handsets are launched three times a month, so even before you’ve sold your stock of the previous model, a new one is introduced.”

Top photo: Theint Mon Soe (aka J) / Frontier