Ka Lone Htar villagers have sought to enlist the help of guardian spirits in their fight against a dam project that would uproot more than 1,000 people.

By RAPEEPAT MANTANARAT | FRONTIER

YEBYU TOWNSHIP, Tanintharyi Region — As a four-year battle continues, residents of Ka Lone Thar last month sought divine intervention in a quest to scuttle plans for a massive reservoir which threatens to put their village underwater.

On February 12th, Sayadaw Pyin Nyar Wun Tha, the abbot of the Ka Lone Htar monastery, asked villagers to set up spirit shrines along the nearby river to help the village secure protection from guardian spirits.

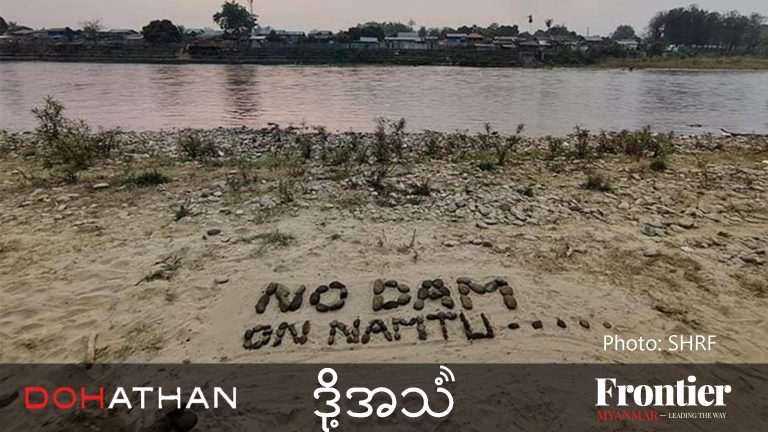

On that chilly and windy morning, people of all ages gathered on the riverbank at the village boundary to reaffirm in prayer their opposition to a plan to relocate hundreds of homes from Ka Lone Htar.

“We do not want to move because of the dam project. We then would like to ask the guardian spirits to protect us and help us to defend our home,” they said, in unison.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Animistic beliefs in the village, as with many other secluded communities in Myanmar, remain strong. The worship of guardian spirits that dwell in rocks, trees, rivers and mountains continues alongside observance of Buddhist precepts, even among members of the clergy such as Sayadaw Pyin Nyar Wun Tha. Nature is respected as a superior force, imbued with the power to provide and to destroy.

On a more practical level, the people of Ka Lone Htar village, located 10 kilometres northeast of Yebyu town, also hope that the shrines will unnerve local officials at a decision-making level, who would suffer the perils of incurring bad luck should the shrines be destroyed by a flooding of the area. If the 627 million cubic metre dam project goes ahead as planned, the whole village would be submerged, displacing more than 1,000 people and destroying thousands of hectares of pristine agricultural land.

Dawei development and its discontents

The villagers of Ka Lone Htar rely heavily on agriculture for living, growing betel, cashews, rubber and fruit in plantations and orchards they say have been in the family for generations. The betel crop alone generated around K100 million (US$80,900) for the village last year.

Farming hasn’t been easy for the village. The Ka Lone Htar stream has already been polluted by a lead mine that opened several decades ago. Villagers can no longer drink from the water because of contamination from mine tailings, which have settled in the riverbed and eroded the stream’s banks. Last year, a flash flood damaged plantations and destroyed an old bridge, killing a local resident when it collapsed into the waters.

These struggles seem inconsequential when compared to the looming threat of the reservoir, proposed to provide a supply of fresh water to the nearby special economic zone project in Dawei. The Thai-backed SEZ, long-stalled due to problems raising capital, has had new life breathed into it by the successful courtship of Japanese investment last December.

In the time it was formulated in 2011, the Dawei SEZ has become mired in controversy, with allegations of land seizures, forced evictions, and insufficient compensation for confiscated farmland. Ka Lone Htar residents claimed in November 2012 that Italian-Thai Development Co Ltd, the primary backer of the SEZ project, had attempted to “force” them to relocate to a replacement village in the days after Vice President Nyan Tun signed a memorandum of understanding with the company.

The reservoir is just one of several projects with the potential to uproot communities without redress. The Dawei Development Association, a local civil society group monitoring the SEZ, has claimed the project could directly affect between 22,000 and 43,000 Tanintharyi residents.

Aside from losing their homes, Ka Lone Htar villagers said they were worried about losing social and cultural attachments to their land that stretch back for generations.

Several proposals have been floated to block the project. Officials from the Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry were invited to last month’s prayer ceremony. Villagers later discussed with them the possibility of turning the area into a natural reserve.

Locals have also suggested establishing an ecotourism program in the Ka Lone Htar, in order to demonstrate to the rest of the country and the region the importance of preserving the area from development.

With a new government soon to take office and questions remaining over the financial case for the Dawei SEZ project, the future of Ka Lone Htar is far from certain. Whether or not the spirits are on their side, they face some formidable opponents in the months to come.