The emergence of a vigilante hit group targeting regime opponents has once again demonstrated the failure of social media companies – in this case Facebook and Telegram – to remove dangerous actors.

By FRONTIER

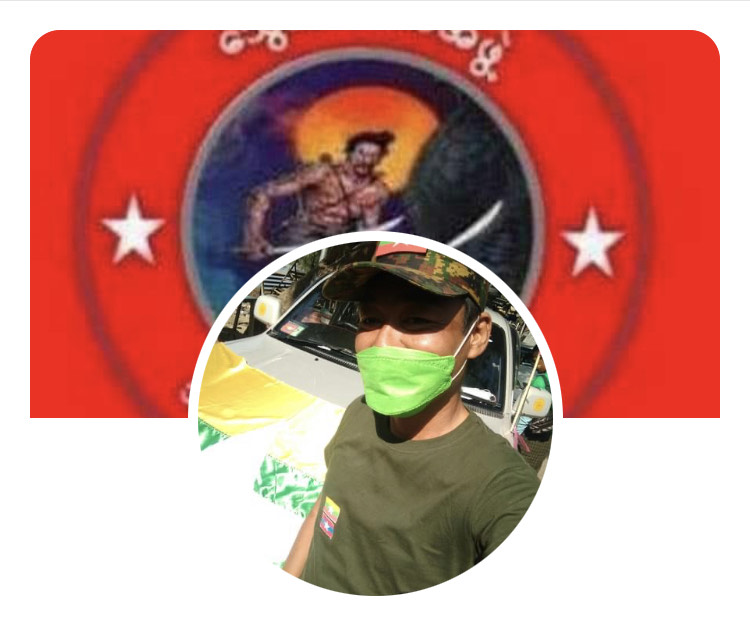

After tea shop owner U Khin Maung Thein was abducted and killed in April, pictures of his body were uploaded to the social media platform Telegram. Hanging around his neck, over his bloodstained shirt, was a lanyard with a strange symbol: a red circle with an image of an ancient Burmese warrior holding two swords.

This is the calling card of Thwe Thauk Apwe, a new pro-military vigilante group whose violent rise has played out over social media, particularly Facebook and Telegram.

The group, whose name literally translates to “blood drinkers” but seems to more figuratively align with the English term “blood-brothers”, has been accused of attacking and killing members of the National League for Democracy and the People’s Defence Forces, as well as their relatives.

On May 10, the NLD said 14 of its members and supporters had been killed by Thwe Thauk Apwe or similar groups in just two weeks, and the killings have only continued since then. While Mandalay has been the epicentre, murders have also been reported in Yangon, Nay Pyi Taw and Tanintharyi.

Khin Maung Thein and his wife, Daw Kha Kha, owned the Sein Win Win tea shop in Mandalay and were passionate supporters of the NLD, which won a landslide re-election victory in November 2020, three months before the militarycoup. Initial reports indicated Kha Kha was also seriously injured in the attack, but the NLD statement claimed she later died.

Ko Aung Myint*, a Mandalay resident and frequent patron of Sein Win Win, confirmed the deaths and told Frontier the couple were “loved by everyone” and were “friendly to every customer”. Their support for the NLD was widely known. In the lead up to the election, the party used the tea shop as a campaign base, Aung Myint said, festooning it with party banners and portraits of State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint. Both civilian leaders were detained the morning of the coup and remain in military custody.

“We are saddened by this loss of life,” Aung Myint said. “They lost their lives at the hands of inhumane people.”

A screenshot of a Thwe Thauk Apwe lanyard posted to Telegram. Many posts also include bodies of victims. (Frontier)

‘A dangerous new breeding ground’

The first reference to Thwe Thauk Apwe that Frontier could find on Telegram came from Han Nyein Oo, an infamous pro-military social media personality that has been at the forefront of shocking online behaviour. The account has directed security forces to arrest business owners opposed to the coup, shared revenge porn of female activists, and posted photos of dead protesters and resistance fighters.

On April 21, Han Nyein Oo accused armed anti-coup resistance fighters of “killing unrelated family members, innocent civilians and monks” and shared a statement announcing the launch of Thwe Thauk’s “Red Operation”. Four days later, a Telegram channel called “Thwe Thout Group” began sharing images of its victims, including Khin Maung Thein and Kha Kha.

The posts were reshared by many prominent Telegram accounts, including pro-military persona Kyaw Swar, who has two accounts – one with over 62,000 subscribers and one with 21,000.

Activists have long called for Telegram to better regulate content in Myanmar. In March, Han Nyein Oo’s primary account with over 100,000 subscribers was finally banned, and in May, a back-up account with over 76,000 subscribers was also taken down. A third account with nearly 50,000 followers remains active.

Daw Wai Phyo Myint, who works for digital rights group Access Now, said Han Nyein Oo’s previous doxxing campaigns were a precursor to the Thwe Thauk content. “If Telegram took action immediately in February and had content moderation, I really think these kinds of issues could be easily avoided,” she said.

Wai Phyo Myint said Telegram may take down some isolated accounts when pressured by civil society, but she hasn’t seen “any policy changes or proactive action”. “The damage was already done by the time they took down the account,” she said, referring to Han Nyein Oo.

Telegram has not responded to numerous requests for comment from Frontier, including for this article.

“In the aftermath of the coup, Telegram has become a dangerous new breeding ground for doxxing and incitement to commit violence in Myanmar,” said Ms Emerlynne Gil, Amnesty International’s deputy regional director for research.

She said that the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights state that social media companies “have a responsibility to respect human rights wherever they operate”.

“Social media platforms must avoid causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts through their own activities, to address such impacts when they occur, and seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services,” Gil said.

However, the principles have been criticised for having no real enforcement mechanism, leaving it to civil society to pressure social media platforms to meet their obligations.

At some point, the Thwe Thout Group channel changed its name to “Bo Talk” and deleted some of the more gruesome posts. Aung Myint said he thought Thwe Thauk members had gone underground because they were afraid of retaliation rather than Telegram regulations.

“They have already calmed down a lot. When urban guerrilla groups in Mandalay killed two of their members, even their Telegram channels changed their names and topics,” he said.

But on May 21, Bo Talk shared pictures of two more victims: the mother and sister of a PDF fighter from Myaing Township in Magway Region. One of them had a Thwe Thauk lanyard around her neck.

Screenshots from Facebook show claimed Thwe Thauk Apwe members making donations to a soldier and Buddhist nationalist monk U Wirathu. (Frontier)

Organising on Facebook

Facebook began more actively regulating content in Myanmar since 2017, when it was implicated in the spread of dangerous hate speech and disinformation during the violent crackdown on Rohingya Muslims, which has since been declared a genocide by the United States.

But Frontier has found that Thwe Thauk Apwe also appears to be turning to Facebook, which is far more widely used in Myanmar, to rally support.

On April 25, for example, a Facebook user called Ba Chit posted about the launch of the “Red Operation”.

“If you love your country and religion, join as much as you can. Do not share this post,” the account said. Pro-military users spreading disinformation and hate speech have long discouraged the sharing of posts in order to evade Facebook moderation; sometimes, they ask followers to copy and paste the post instead. As of May 18, the post had just four shares, but more than 700 reactions, and remained online. The post was taken down after Frontier reported it to Facebook.

Ba Chit has also posted about Pyusawhti paramilitary groups; these militias have been particularly active in Sagaing and Magway regions, where they fight against resistance forces, often alongside military soldiers. The junta has admitted to supporting Pyusawhti militias.

On January 22, Ba Chit posted that “our group will go and fight together with the Pakokku militia”, referring to a township in Magway Region. On April 27, he encouraged new recruits to join a Mandalay Pyusawhti, saying they must provide their age, phone number address and citizenship scrutiny card.

“Every Pyusawhti group is organised and does not accept unruly people,” he wrote.

The Ba Chit account also made a Facebook post appealing for donations, which seemed to reveal that the name of the person operating the account is U Myint Zaw Oo.

Another pro-military activist, U Kyaw Htun Thein, also appears to be linked to Thwe Thauk. He runs at least six different Facebook accounts, one of which uses the Thwe Thauk logo as its cover banner. In a livestream on April 28, which accumulated over 8,400 views, he confirmed the existence of Thwe Thauk and claimed to be a member.

“One thing I can guarantee is that this group really exists, but I will not say who is in this group and who is directing it,” he said, claiming there were branches in Mandalay, Yangon and Nay Pyi Taw. “We do not kill every NLD supporter. But if this man is supporting terrorism, we will kill him. If he is not at home, we will kill his family.”

Inciting violence is a violation of Facebook’s terms of service. The video was removed after Frontier reported it to Facebook.

Both Kyaw Htun Thein and Ba Chit appear to have links to ultranationalist anti-Muslim monk U Wirathu. On several occasions, Kyaw Htun Thein has posted pictures of himself on Facebook donating money to Wirathu. In April, Ba Chit posted that he provided security for Wirathu during a public sermon, but Frontier could not independently verify this.

Another Facebook account, called Aung Ko Ko Min, claimed to be a spokesperson for Thwe Thauk. When the grandfather of an actor who joined the armed resistance was killed in Yangon, Aung Ko Ko Min gloated on Facebook.

“How do you feel now? I think you are crying in the jungle. Your dear grandfather has kept a coin in his mouth for you. Hello, all patriots from Mandalay, the Yangon Thwe Thauk group also showed their skills,” he wrote.

Aung Ko Ko Min runs an organisation called Eagle Humanitarian Charity, which collects donations to support the military. On April 24, he uploaded a photo showing himself directly delivering aid to a soldier.

Wai Phyo Myint said Facebook is much more responsive than Telegram, “but there are still some serious problems” with content moderation. “If we say, look at this, these are the evidence, they take it down. If we miss it, they miss it,” she said.

Frontier had a similar experience. While reporters viewed many posts that clearly violated Facebook’s terms of service, they were taken down only after Frontier reported them.

Rule of law collapses

On April 29, a pro-military media outlet called Myanmar Gon published an interview with a supposed spokesperson of Thwe Thauk that was widely shared on pro-military Telegram channels.

The spokesperson listed the five categories of people targeted for murder: PDF fighters and their families, PDF fundraisers and their families, journalists who are “selling out the country” and their families, family members of those living abroad who are “inciting murder”, and those who encourage violence against military supporters online. A sixth category, those who encourage “social punishment” of military supporters, would have their property, such as businesses and cars, destroyed.

He said Thwe Thauk was formed by “people who truly love their nation and country and who want to see Myanmar develop and prosper”, and they were planning to establish groups in 14 townships, across Nay Pyi Taw, Yangon, Mandalay and Sagaing. “It will be done nationwide,” he said.

U Aung Thu Nyein, with the Institute for Strategy and Policy – Myanmar, said the emergence of these groups and the continuation of anti-military assassination campaigns represents “the collapse of the rule of law”.

Many are questioning if the military is behind Thwe Thauk, particularly given it has admitted supporting Pyusawhti groups.

Aung Thu Nyein said it is difficult to say for certain. “One thing is for sure, there seems to be financial backing and power behind them,” he said.

Gil from Amnesty pointed out that the junta has made “no substantive effort” to combat the murder campaign. “At the very least it is allowing this group to run amok with impunity,” she said.

NLD supporters are in no doubt, however.

“Our people believe that [Thwe Thauk] is led by the military and working with the police,” said Aung Myint, the Sein Win Win customer.

Ko Demo Aung*, a member of the NLD youth committee in Mandalay, called Thwe Thauk and the military “two peas in a pod”.

He fled the city in March after being threatened by soldiers and having his house raided twice. As a protest organiser, he was charged under section 505-A of the Penal Code for incitement and under the Natural Disaster Management Law for violating COVID-19 restrictions.

“The dictators of our country consider the NLD and its members, who have the full support of the people, as their enemies,” he said.

Demo Aung theorised that one reason the military may be relying on Thwe Thauk is to try to portray the political crisis in Myanmar as a two-sided dispute between civilians of different political beliefs, rather than a one-sided system of oppression by the military.

Gil agreed, saying relying on proxies makes it more difficult for perpetrators to be held responsible, and easier for incidents to be dismissed as “local disputes or personal conflicts”.

“Myanmar’s military has a long track record of implicitly endorsing or looking the other way while others do their dirty work, whether it be hired thugs at protests or pro-military militias,” Gil said.

For the friends and family of the victims, there is little hope of pursuing justice through the regime-controlled legal system. “If I were a member of that family, I would have to move to avoid losing more lives rather than filing a [criminal] complaint [to police],” said Aung Myint.

Demo Aung agreed, saying it would be “easier to squeeze water from a rock by hand” than to get justice through the junta’s legal system.

* denotes the use of pseudonym upon request for safety reasons