Since the February 1 coup pushed Myanmar’s economy off the edge, residents living in informal housing on the urban fringe – already battered by the COVID-19 pandemic – are being pushed to the brink of starvation.

The exigences of extreme poverty have left Daw Than Aye, 57, with little energy or attention left to follow politics.

All she knows of the political crisis that’s engulfed the country for the past three months, she said, is that it’s made it impossible for her children – three sons and three daughters, all strong and healthy and aged between 17 and 30 – to find work.

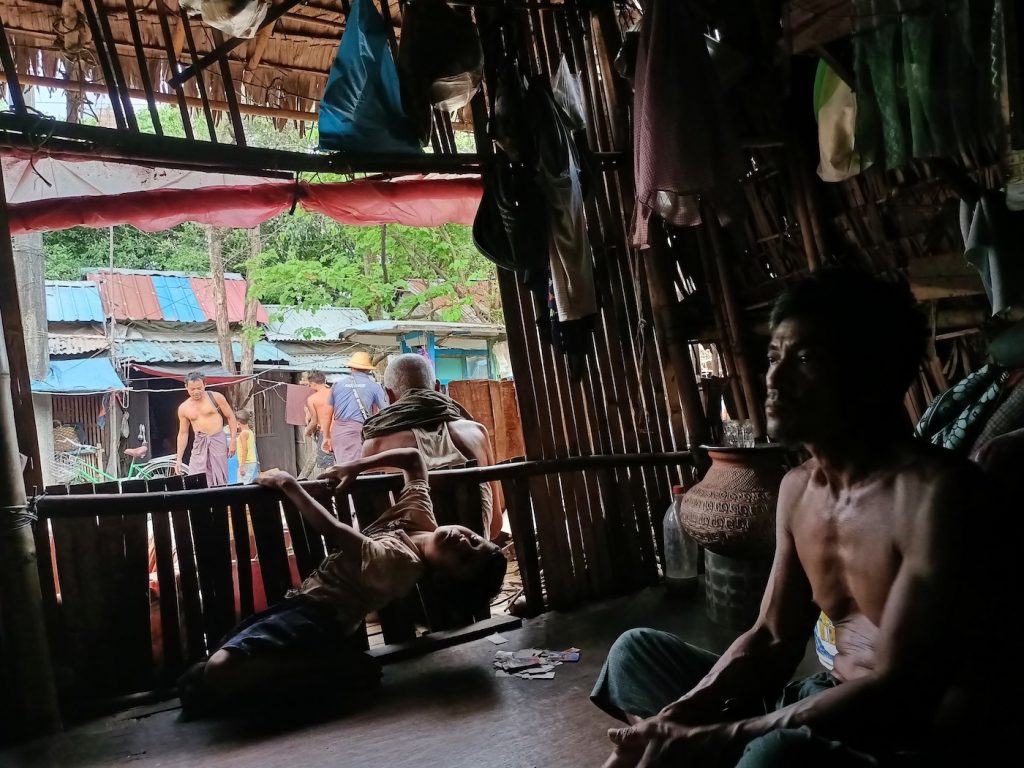

“There are six people in my family who are able to work, but as you can see, they are sitting around at home, which they do all day long,” she told Frontier one recent afternoon, as she sat outside her tumbledown shack in industrial Hlaing Tharyar Township, on Yangon’s western outskirts.

Since the February 1 coup began ravaging Myanmar’s economy, Than Aye said the family has been finding it harder and harder to earn enough money to feed everyone. The jobs her children previously relied on – in wholesale markets, construction sites and garment factories – have all vanished.

“When I wake every morning, my first thought is where I’ll get money for today’s meals,” she told Frontier. “Our staples are rice, ngapi (fish paste) and vegetables, but some days we can’t afford the vegetables.”

The family moved to Hlaing Tharyar’s Yay Oak Kan ward – where more than 1,000 other families also live in an informal settlement – from Ayeyarwady Region’s Kyonpyaw Township 12 years ago so her sons could find work. But battered by a year-long pandemic and an even more devastating military coup, they are now among the hundreds of thousands of informal settlers, or “squatters”, who’ve found themselves broke, out of work and on the brink of starvation

“Before the coup, trucks from the construction sites used to come here every morning to collect workers, but I think work on the sites has halted,” Than Aye said. “Now, everything has stopped.”

‘We will have to suffer’

Families in informal settlements like Yay Oak Kan generally cobble together their own ramshackle lean-tos and informal structures to sleep in, usually on unoccupied land in industrial townships. Most don’t pay regular rent but must sometimes pay bribes to local administrators.

In 2016, the Ministry of Construction’s Department of Urban and Housing Development estimated that in Yangon alone there were some 440,000 of them living in 110,000 households, mostly in encampments in outer townships such as Hlaing Tharyar and Dagon Seikkan.

In 2017, as part of a resettlement plan, the Yangon regional government began issuing “smart cards” that gave them priority when applying for low-cost government housing. But the programme was only open to those earning between K100,000 ($62) and K300,000 a month, which is beyond the reach of most who Frontier spoke to.

“I always keep the smart card in a safe place, but I’ve heard nothing about the housing programme since the card was issued [in late 2017],” said Daw San San Win, 57, who also lives in the camp at Yay Oak Kan. “It’s obvious that they [the military] will not continue the affordable housing plan for squatters.”

Indeed, any hopes that those living in informal settlements may have harboured of moving into more secure housing seem to have been dashed by the coup. While there have been no formal statements about the future of these encampments, San San Win said she and her neighbours are all on edge about rumoured evictions. They have heard that new, junta-appointed ward administrators are demanding cash payments of K30,000 from some households, and demolishing structures when families can’t pay.

Frontier could not locate anyone who had faced such a fate or verify that the process was taking place, but many interviewees claimed to know of a “friend of a friend” to whom it had happened.

Daw San San Win, right, worries she’ll be evicted from her informal housing. (Frontier)

The view from Daw San San Win’s home. (Frontier)

Junta-appointed ward administrators in Hlaing Tharyar declined to be interviewed. They also largely do not allow journalists into their wards; Frontier had to pose as a surveyor for a charity group to interview informal households in Hlaing Tharyar.

While there, Frontier saw about 30 homes that had been demolished in the third week of April in Shan Kyaung ward, but one 10-household leader said they were demolished at the request of the landowner, not because the households were unable to pay K30,000.

In the past, ward offices provided military dictators with a network to monitor and control people’s activities at a granular, household level. Under the civilian government, the officers went from military appointees to popularly elected officials, and ward administration was moved from military to civilian control. Since the coup, however, the junta has been reinstalling its own appointees, who then select 10-household leaders to help supervise the ward.

Ma Nwet Mu, a longtime Shan Kyaung resident, said the junta’s ward administrator has been demanding that newcomers pay a one-time fee of K30,000, and had also hired local thugs to patrol the area for new faces, but the 10-household leader claimed to not know about this either.

“I have not heard anything about squatters having to pay K30,000. Our ward administrator has said nothing about that,” he said. “I think that will depend on the attitude of each ward administrator. If one of them wants to abuse their power, this is one way they could do it.”

When the smart cards were first issued, San San Win had a distant hope that she may someday own a home. Now she worries about being evicted from her shack.

“I have no hope of finding that kind of money right now,” she said.

Her daughters help her with money they make at a nearby garment factory, but they fear the factory may be closing at the end of May. “Their wages barely cover food for us,” San San Win said.

“There’s nothing we can do about it. We will have to suffer whatever they decide to do.”

No work, no aid

When Daw Tin Tin’s daughter had a factory job, she shouldered the burden of supporting her mother, an ill sister, and her own two children. But her daughter has had no work since early April, when the factory closed for three months.

“My daughter is a single mother and the family breadwinner. When the factory closed, it gave its employees three months’ unpaid leave,” Tin Tin said. “Now she’ll have no income until July” – and, she added, it is uncertain if the factory will even reopen then.

The 66-year-old has had to take out high-interest loans from loan sharks that she can’t afford to repay.

“I have debts totaling more than K700,000 from four lenders. The interest rates are between 20 percent and 30pc a month, so the interest payments alone are about K200,000 a month. When I can’t pay that, it’s added to my debt, which means I’m paying interest on my interest,” she said.

She said she’s been trying to find work but has been repeatedly rejected because of her age, and loan sharks are constantly hounding and cursing at her.

U Maung Win, 55, used to work as a day labourer loading and unloading bags of rice at a wholesale market. Asked about the coup, the Yay Oak Kan resident said he doesn’t care who runs the country as long as his life gets easier. But he admitted that, so far under the junta, that has not been the case.

“Before the coup we had two crews, one working during the day and the other at night. We can’t work at night anymore because of the curfew, and the number of us trying to work on the day crew far exceeds the need,” he said.

Throughout the pandemic, hundreds of thousands of workers were laid off in Yangon, but multiple rounds of cash handouts from the National League for Democracy government and assistance from volunteer welfare groups helped ease some of the burden.

Than Aye said she received K80,000 in government relief last year – one payment of K40,000 and two of K20,000 – as well as rice, cooking oil and other basic necessities from community groups. Since the coup, she and other informal residents in Hlaing Tharyar said they received a one-off handout from the military of about two kilogrammes of rice and some cooking oil but no cash assistance, and that the junta’s ward administrators are preventing charity groups from distributing cash or in-kind donations.

“A few weeks ago a social welfare group came to the ward to distribute some basic goods, but the ward administrator’s aides did not allow them to enter,” Than Aye said. “The ward administrator said they needed to register their names at the ward office, so they left without distributing the aid because everyone’s afraid of giving them identifying information at the moment.”

Since a brutal crackdown on protesters in Hlaing Tharyar on March 14, local volunteer groups, who assisted the injured protesters and handled the dead, have been maintaining a low-profile to avoid attracting the attention of junta supporters in the township. They’ve removed signboards from their offices and are parking their vehicles out of public view.

Than Aye said the situation is now more dire than at any time during the COVID-19 outbreak, with everyone in the informal camps fighting hunger pangs.

“We were not starving during the pandemic,” she told Frontier. “Now we are starving.”