Myanmar’s private sector newspapers need to start turning a profit but face challenges from state-run publications and digital media.

By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER

A printing house in Yangon’s outskirts. (Ann Wang / Frontier)

In 2013, parliament approved legislation allowing private daily newspapers for the first time in 50 years.

“We thought, ‘Our dreams have come true’,” said U Ko Ko, who founded Democracy Now soon after the 2013 Media Law was enacted. “We never calculated the risk; we never calculated profit-loss; we wanted to see our dreams come true,” he said.

U Ko Ko was not alone. Private sector media companies were eager to go daily after being restricted to weekly or monthly publications and stifled by rigorous government pre-publication censorship that was lifted in August 2012. Within weeks, titles such as

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

7Day Daily, The Daily Eleven, The Voice, Yangon Times and Freedom Daily were rolling off the presses.

But just as quickly Myanmar became a newspaper graveyard. In a 2013 report, market research firm MMRD said eight percent of total advertising revenue in 2013 and 2014 went to private daily newspapers, most if that went to state-run publications, Myanma Alinn, Global New Light of Myanmar and the Daily Mirror. The newcomers folded one by one until only a handful was left.

Three years later, few of the survivors are turning a profit. Distribution and advertising revenue are eclipsed by state media, which have been operating for decades and have seven printing houses throughout the country.

“If I told you the exact amount of our losses, you would be shocked,” said U Ko Ko.

This does not mean there’s no market for newspapers in Myanmar. In its 2013 report, MMRD project that advertising revenue would nearly double, from US$180 million to $320 million this year.

“There are between six and 13 people million reading a newspaper. We’re not servicing that market; that’s plain to see,” said Ross Dunkley, an Australian media entrepreneur who co-founded the Myanmar Times in 2000 with Sonny Swe, the chief executive of Frontier Myanmar. “In Myanmar we have an entrenched desire for newspapers. They’re going to have them no matter what,” said Mr Dunkley.

But what people read each day is still dominated by the state. Papers under the government’s News and Periodicals Enterprise have a circulation of about 200,000, whereas Mr Dunkley said titles such as Myanmar Times and Daily Eleven do well to break half that figure. “Their reach is the Yangon-Mandalay Highway route, basically,” he said, adding, “That’s not acceptable in any other country.”

Hot off the presses

On the surface, government papers have both legacy and infrastructure to thank for their strength. State-controlled presses are strategically located for distribution throughout the country, but the private sector dailies are published almost exclusively in Yangon, with one in Mandalay. Even when they can afford to distribute in distant markets such as Kachin and Rakhine states, the state-run dailies have a head start.

In reality, the printing capacity of NPE is not much better than the private sector, Mr Dunkley said. The state has more presses but many of those outside Yangon are old and poorly maintained.

U Ko Ko said the NPE can flood the market with its newspapers, undercut the private sector and sell advertising at heavily discounted rates. The content is basically propaganda, he said, but readers are used to it. They buy state-run papers for government announcements, obituaries and weather reports, just as their parents and grandparents did.

U Ko Ko blames the state media juggernaut for almost all the woes of the private sector and goes so far as accusing the NPE of intentionally strangling the market to muzzle the Fourth Estate. He says the government should reduce the number of state-run dailies and subsidise private media in the public interest.

“They are indirectly killing us,” he said. “If today the public newspapers stopped, tomorrow would be completely different.”

Mr Dunkley does not accept the evil monopoly narrative.

Yes, he said, government interference does harm newspapers through imprecise legislation such as the State Secrets Act, rigid rules in the 2013 Media Law, unofficial intimidation and back-channel economic sabotage.

More detrimental to the private sector, however, have been basic management errors. Most media companies are likely to fund growth through profits alone, and are either wither unwilling or unable to attract the venture capital needed to buy presses, hire staff, expand reach and ultimately, attract new advertisers.

“They want to show the world we are a real democracy,” he said. “How can you say this is a democracy without a newspaper?”

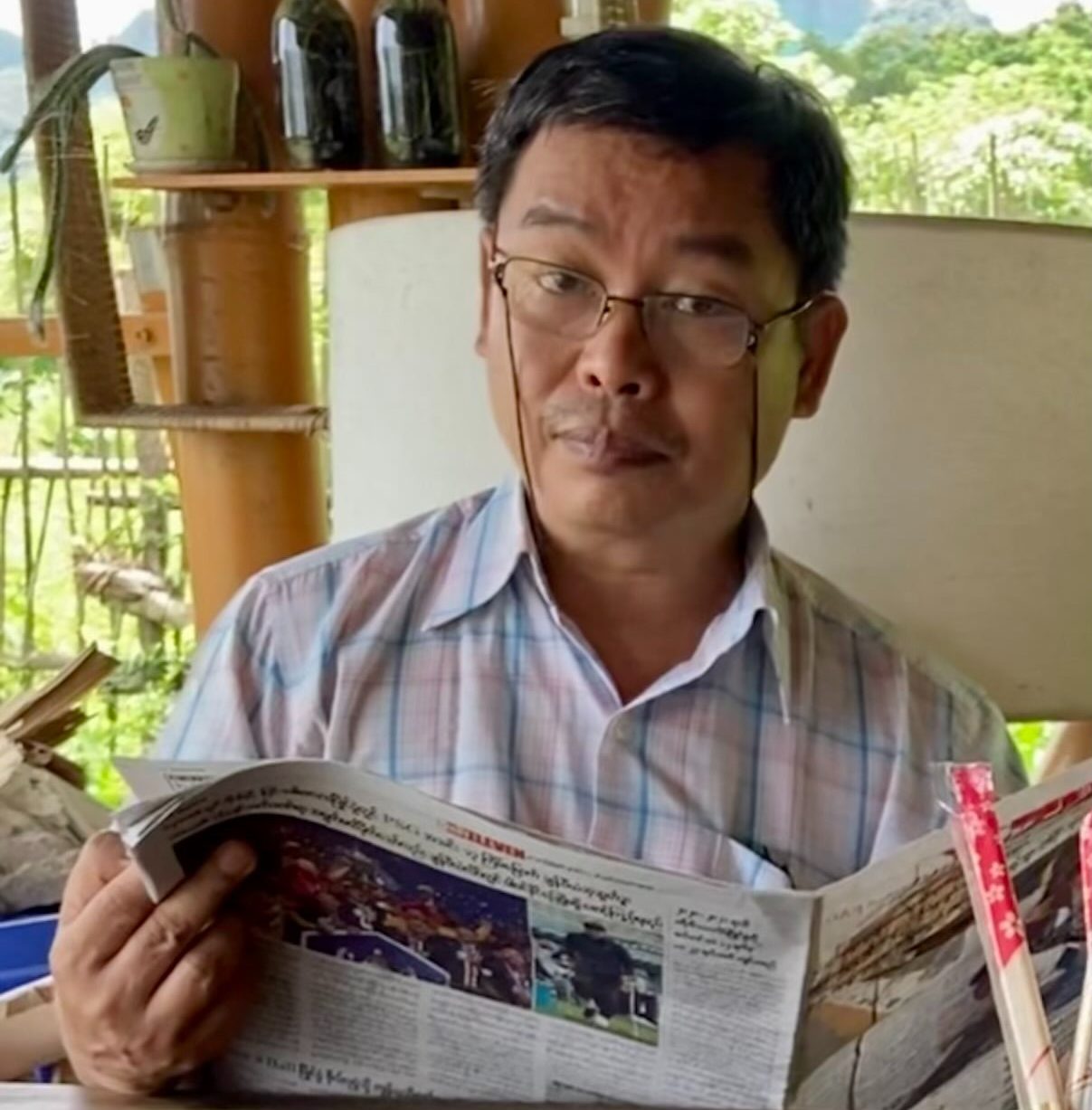

A newspaper vendor in Yangon’s gridlocked traffic. (Ann Wang / Frontier)

Standards

Mr Dunkley also said that journalism standards in Myanmar need to be higher.

“You’ve had an industry that has been isolated for 50 years. There had been almost no journalists practicing in this country for decades, no editors who could train people to take up the mantle,” he said. “It all contributed to a pretty moribund sector.”

U Myint Kyaw is chairman of the Myanmar Journalist Network, a resource, network and advocacy organisation for journalists. He agrees that Myanmar has an immature media industry, but says it is not because publications have poor standards. It is because they do not have the capacity to uphold them.

“Most journalists, their salary is very low,” he said, adding that reporters earn about $200 a month and editors between $400 and $600. “The media owners don’t spend their money on capacity building…they just hire and then send to the field, that’s it. Not one month of training,” said U Myint Kyaw.

He said that after six months to a year on the job, most young journalists attend training workshops offered by a handful of organisations, such as USAID and BBC Media Action. The newspapers have limited resources to develop the quality journalists needed to build a new foundation in the media.

U Myint Kyaw agrees with U Ko Ko that a lack of business success is to blame for low standards, not vice versa. Either way, both standards and capacity must improve before newspapers can begin turning a profit.

Taming the digital beast

It is difficult to tell what impact the internet is having on the newspaper industry. In 2012, there were fewer than 200,000 internet users, but this year Telenor said more than half of its 10 million SIM card holders use data. For newspapers, web content is vastly cheaper to distribute than a physical product. It is also very difficult to make money from websites.

The young generation is used to sharing information for free on social media, said U Ko Ko, adding that they read Facebook summaries of reports without actually visiting the page itself. “They will read on Facebook that there has been a fire, but they won’t read the article to find out how many houses burned,” he said.

The content can enjoy greater reach, but not necessarily the advertising.

Stewart Becker, circulation director at the Myanmar Times, agrees that print is losing out, even in one of Southeast Asia’s least connected countries, and there will be casualties.

“It’s going to narrow the field; it’s going to consolidate the field. And the race is going to be, ‘Who’s got the best mobile app? Who’s going be on your device and why’?” said Mr Becker.

But for those that survive, he sees the web as a tremendous opportunity, not a threat. His strategy: Get users first, then find a way to make money.

The go-to monetisation strategy practiced by Facebook and Google is what Mr Becker calls the “surveillance paradigm,” or offering service in exchange for the privilege of selling user data.

“What I’d like to do is monetise it in other ways,” he said. “Specifically, with services: For example, maybe we could get grocery delivery. Maybe we could do online shopping. Because once we’ve got the numbers and we know you are, let’s say, a Myanmar Times mobile app customer, we have the ability to reach you directly.”

None of these ideas are officially planned by the Myanmar Times. Mr Becker was making the point that Myanmar’s digital revolution is go-big-or-go-home. “It requires a leap of faith. It requires going boldly into the market, hoping that you will get the numbers and figure out a way to monetise it,” he said.

Regardless of the challenge, newspapers have no choice but to try. People are going online, and if they don’t find legitimate news, they’ll simply turn to blogs and social media. Either way, they aren’t picking up a paper.

The Fourth Estate

Mr Dunkley is less optimistic. “In Myanmar [monetisation] is more difficult because income levels are so low. People’s expendable income is such that it’s pretty hard to get a lot money out of someone only earning $150 a month.”

Mr Dunkley doesn’t believe Myanmar will abandon newspapers for digital, but says the situation will get worse before it gets better. He predicts that more private sector dailies will close after the election, leaving only four or five serious daily publications.

U Ko Ko agrees. “At this point, we just want the minus to become less. We’re not expecting a plus.”

But he has faith in the industry’s future. Myanmar has been waiting for private sector newspapers for 50 years and not even the government would want the country’s newsstands to go empty, even it means reducing the reach of the state-run papers and subsidising the private sector press.

“They want to show the world we are a real democracy,” he said. “How can you say this is a democracy without a newspaper?”