Myanmar citizens have the legal right to own a firearm but only a privileged few have licences and the Ministry of Home Affairs is coy about the matter.

By KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

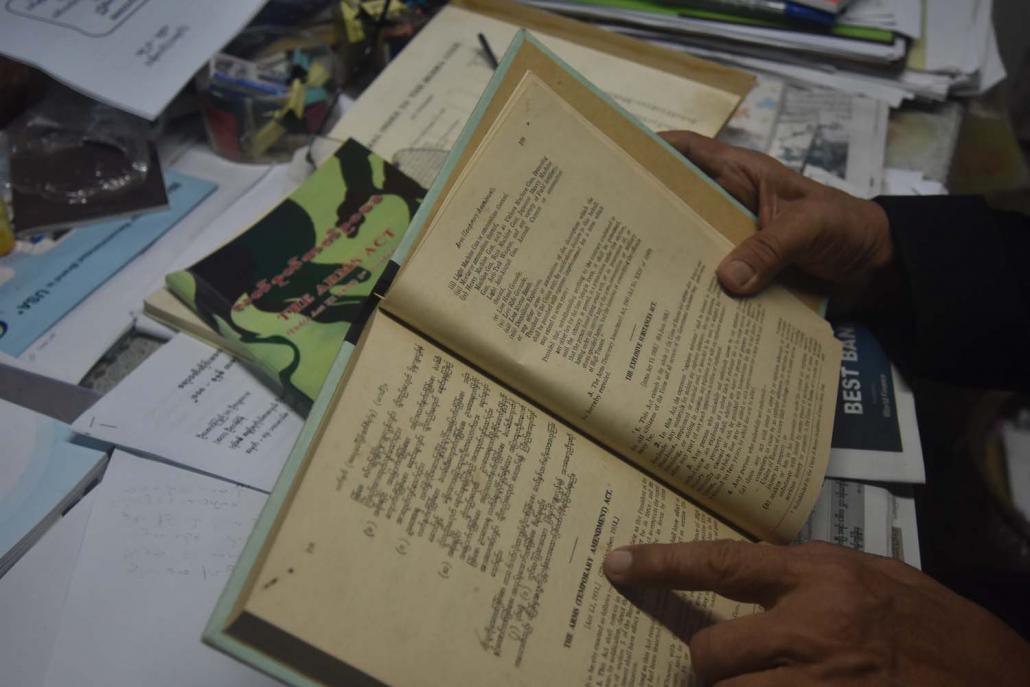

THE HISTORY of gun ownership laws in Myanmar is marked by changes and exceptions under colonial rule and amendments that followed independence in 1948.

Generally speaking, Myanmar citizens have the right to own firearms but licences since the 1960s have only been issued to a privileged few.

The first such law, the Indian Arms Act, was enacted in 1878 when Burma was under British colonial rule. It applied throughout the country but subsequent changes, in 1924 and 1948, provided for exceptions under the Shan States Arms Order and Chin Special Division Act, respectively.

Legal experts often speak highly of the way the democratic government managed the Arms Act during the first decade after independence. Getting access to a permit depended less on having high-ranking connections than being able to demonstrate a clear need to carry a weapon.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

However, they say that administration of the act has become complicated and has created a situation where the right of a citizen to own a firearm lacks clarity.

The first amendment to the Arms Act was made in the last year of British rule. However, the Arms (Temporary Amendment) Act, 1947, was repealed by independent Burma’s first government in 1949. Just two years later, a new amendment was enacted.

Legal experts say the right of citizens to own firearms for self-defence has been eroded by successive governments over the years. Instead of making a decision based on whether a person needs a firearm for self-protection, these governments have instead handed out licences as a privilege to their loyal followers, legal experts claim.

“There is a need to enact a new law or draft a policy which guarantees that citizens have the right to self-protection,” said lawyer U Khin Zaw (Mayangone), adding that citizens would otherwise be unable to prevent themselves from becoming victims of serious crimes, such as armed robbery, banditry and kidnapping.

After General Ne Win seized power in 1962, the ruling Revolutionary Council military government ordered the confiscation of all firearms owned by citizens. It would hold onto these firearms for well over a decade, and most would not be returned to their original owners.

After the transition from a military regime to the Burma Socialist Programme Party government, the government implemented a new policy on firearms in 1977 that resulted in the repeal of three orders issued by the democratic government in 1959 under the 1951 act.

Although the policy is the cause of many complications, legal experts say its intent was to ensure that confiscated licensed firearms were distributed among members of the BSPP and retired civil servants, including former members of the Tatmadaw, rather than returning them to their original owners.

Lawyer U Kyi Myint says that Myanmar firearms laws have generally given the authorities significant discretion in dispensing licences, stating only that they should go to people of “dignity” and “good character”.

Kyi Myint said this was not a problem during the post-independence democratic government, but subsequent military administrations gave priority for firearms ownership to high-profile military veterans and those with whom the juntas were closely associated.

Former Pyidaungsu Hluttaw Speaker U Shwe Mann in a recent book related how, after losing the election three days later, he slept with a gun under his pillow – a rare example of a civilian holding a licensed firearm. (AFP)

“None of these decisions met the norms of democracy,” said Kyi Myint, who is also chair of the Union Lawyers’ and Paralegals’ Association. “The government and parliaments need to decide what to do; whether to continue the procedure inherited from the military dictatorship or introduce legislation based on that used by the AFPFL [Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League] government,” he said, referring to the government that ruled from independence to 1958, when it split into factions.

In May, Thura U Shwe Mann, a third-ranked member of the State Peace and Development Council junta and a former powerful politician, revealed in a book that he carries a licensed weapon for self-defence.

Shwe Mann, who served as Pyithu Hluttaw speaker under the previous Union Solidarity and Development Party government, was dramatically sacked as USDP chair in 2015 and since 2016 has served as chairman of the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw’s Commission for the Assessment of Legal Affairs and Special Issues.

In The Lady, I and Affairs of State, he recounts the night of his loss in the November 2015 general election. Late on polling night, he realises that he has lost and goes to bed with his wife. He writes: “When she saw me take the gun and put it under the pillow as usual, she said, ‘You don’t need to do this. You lost the election. People who want you to lose will be satisfied. You are no longer in danger.’ Although what she said was correct, I kept it as usual for safety.”

The admission by the former general attracted attention because it is unusual for any civilian, including those who have retired from the military, to be given permission to own and carry a firearm.

It is not widely known that most citizens are entitled to own and carry a firearm for self-defence and that there are shops where the weapons are sold.

However, some citizens believe that strict controls must be retained on gun ownership in the interests of public safety and because there is no rule of law in Myanmar.

The Weapons Act of 1878 has been amended several times but is still the primary law regulating the licensing of firearms. (Kyaw Lin Htoon | Frontier)

Shan State Hluttaw MP U Nyi Lay Chan (National League for Democracy, Pindaya-2) raised the issue of the civilian ownership of firearms in the assembly last December.

“I asked that question because I want to know clearly how the government issues licences for firearms,” he said, adding that there was concern about the potential risk of their use in robberies, kidnapping, banditry and crimes associated with the drugs trade.

Shan State Minister for Security and Border Affairs, Colonel Naing Win Aung, replied that four civilians had been licensed to own weapons.

Burma News International quoted the minister as naming the four as prominent businessman U Aung Ko Win, who owns the Kanbawza Group of Companies, which includes KBZ Bank; U Aung Than Htut, a retired lieutenant-general turned parliamentian (USDP, Laukkai-1); Dr Sai Kham Leng, the medical superintendent of the Jivitadana Sangha hospital in Taunggyi; and Shan State MP U Myint Lwin (USDP, Kutkai-2), who heads a militia group.

A police major in Yangon told Frontier on condition of anonymity that approval for civilians to own firearms came from the highest levels of the Ministry of Home Affairs. In his 30 years as a member of the Myanmar Police Force he had never handled an application for a firearms licence, he said.

The Ministry of Home Affairs declined to comment when Frontier sought information on the number of licensed firearms owned by civilians.

Lawyer U Thein Aung, a patron of the Myanmar Lawyers’ Network, said that if the legislation was amended, it should impose tighter restrictions on eligibility for a firearms licence.

“What’s really important is why a person needs a gun,” he said.

Thein Aung said that despite restrictions on gun ownership, they were often used in criminal cases, especially those involving narcotics.

Some legal experts support the idea of issuing firearms licences for self defence to certain categories of people, such as wealthy businesspeople, lawyers involved in cases that may involve threats to their lives and those of their families, and civil servants working in unsafe areas.

Kyi Myint said that after nearly 70 years of military dictatorship, it wasn’t strange that the “majority of people” have come to believe that only security forces should hold arms.

“But now is the time to restore this original right to our citizens so that they are able to defend themselves, if necessary,” he said.