Myanmar has not executed a convict for decades, though they continue to be put on death row. While some call for capital punishment to be scrapped, others are demanding it for child rapists.

By EI EI TOE LWIN | FRONTIER

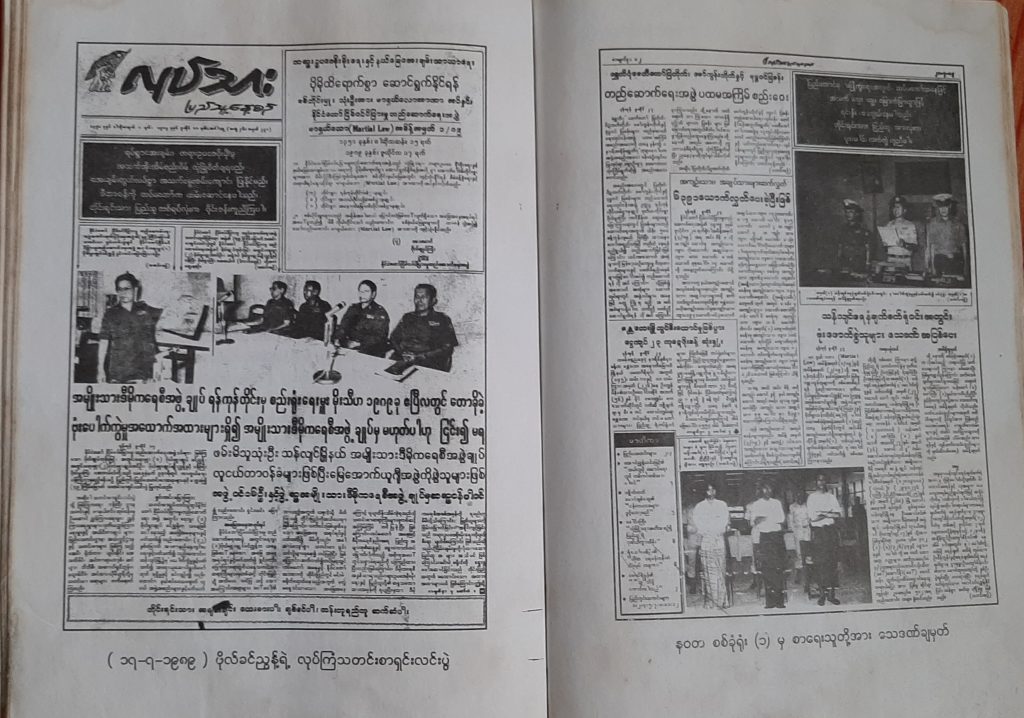

On July 7, 1989 – the 27th anniversary of the Ne Win regime’s bombing of the Rangoon University Student Union building, one day after it gunned down dozens of student protestors on campus – a bomb exploded at a fuel depot in Yangon Region’s outer eastern Thanlyin Township.

When the bomb went off, Ko Than Zaw, 57, was at the National League for Democracy head office in Yangon for a ceremony marking the anniversary of the student union bombing. In the following days, he busied himself planning a July 19 protest to mark Martyrs’ Day, the commemoration of the 1947 assassination of Bogyoke Aung San and eight others.

At about 4am on July 13, Than Zaw was awoken by a knock on his door. Government officials demanded to check his home for guests under the Ward and Village Tract Administration Law’s hated “midnight inspections” clause, which was abolished in 2016. When he opened the door, he was handcuffed and taken away by military and police officials.

“At the time, I thought it must be because I’d attended the July 7 ceremony at the NLD office, or because of my role in organising anti-government protests on Martyrs’ Day,” he told Frontier.

In fact, he and two other young NLD activists were being arrested for the bombing in Thanlyin. For several days, all three were tortured at a government facility and forced to give false confessions.

“They didn’t let us sleep or give us anything to eat,” he said. “They were making us go crazy. I didn’t want to go crazy.”

On July 27, they appeared before a military tribunal chaired by Lieutenant Colonel Aung Nyunt. Despite having retracted their confessions and denying involvement in the bombing, the military judge ordered all three to death by hanging. Than Zaw was just 26 years old.

Capital punishment has a long history in Myanmar and was widely used to cower dissidents into silence during the era of military rule. Although no death sentences have been carried out for more than three decades, many wish to see it remain on the books – and implemented – for the most heinous of crimes such as child rape. However, some progressive human rights activists want to see capital punishment expunged from the lawbooks, seeing the penalty as inhuman and still prone to abuse by the state.

“When the judge announced the death sentence, I was outraged with the judicial system because I had not committed a crime,” Than Zaw said. “I was so upset by the feeling that citizens have no legal protection in this country.”

Military Intelligence later arrested Karen National Union explosives expert Ko Ko Naing, who under interrogation confessed to bombing the refinery and said that no NLD members or student activists had been involved.

On January 1, 1990, Than Zaw was removed from death row, but he was not freed; his sentence was commuted under a presidential pardon to life in prison because, he said, “[the military regime] did not want to admit we had been wrongly convicted.”

On July 1, 2012, after 23 years behind bars, Than Zaw walked free. By then, his father, mother and older sister had all passed away.

Abolitionist in practice

Capital punishment has been used in Myanmar for centuries; thousands were executed during the Konbaung dynasty (1752-1885), and it continued under British rule and through the period of military rule that followed the country’s brief flicker of post-independence democracy. Since taking power in 2016, the National League for Democracy government has made no move to abolish it.

But in Myanmar and across the world, the question of whether such a policy aligns with modern ideas of human rights is hotly debated. Activists and ethicists have for centuries railed against what they see as state-sanctioned murder, and the United States is today the only western, industrialised country in the world that continues to implement it.

At least 657 executions were carried out in 20 countries in 2019, according to Amnesty International – down 5 percent from the previous year and the lowest number the human rights watchdog had recorded in more than a decade. Most took place in China, followed by Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Egypt.

As of December 31, 2019, 106 countries had abolished capital punishment for all crimes. Eight still handed down death sentences for “exceptional crimes” and 28 for crimes such as murder, but none of these countries has actually executed anyone in the past 10 years, leading AI to consider them to have abolished the death penalty “in practice”.

This means that a majority of the nations of the world have abolished the death penalty outright, and more than two-thirds have in practice.

While AI considers Myanmar, which has not executed a convict since the late 1980s, in this latter category, some activists want the sentence abolished outright. Even in the best of judicial systems, absolute certitude of culpability is rarely achievable, they argue, and death precludes the possibility of personal rehabilitation and reform. Besides, handing the state the power to kill its citizens is fraught with problems, and even more so in a fragile and transitional democracy with weak legal institutions and a politically powerful military.

When emotions run high

U Aung Myo Min, executive director of civil society group Equality Myanmar, which has urged the Hluttaw and the president to abolish the death penalty, says capital punishment violates article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which declares that, “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.”

Even with a civilian government, he said problems in Myanmar’s legal system make capital punishment too risky to leave on the books. “The judiciary in Myanmar is not trustworthy, and [without a trustworthy judiciary], the death penalty is unjust,” he told Frontier. He said he thinks the public generally agrees with him – except in the particular case of child rape.

In 2018 there was a record number of reported child rape cases – 1,028, up from 887 the year prior, according to figures from the Ministry of Home Affairs. Five people were sentenced to death that year for both raping and murdering children, and child rights groups petitioned parliament and the president in support of mandatory capital punishment for the crime, even if the child survives.

In June 2018, Pyithu Hluttaw MP Daw Khin Saw Wai (Arakan National Party, Rathedaung) tabled a proposal calling for the government to enact a special law on child rape that allowed for offenders be executed. She said it was a response to her constituents’ demands. “As a representative of the people I must pay attention to their voices. And, as the mother of three daughters myself, I sympathise completely with the calls for child rapists to face the death penalty,” she said.

She was encouraged in part by U Thein Nyunt, child rights activist and chair of the New National Democracy Party, whose lobbying informed much of her defence of the proposal. While representing Yangon’s Thingangyun Township in the Pyithu Hluttaw from 2011 to 2016, Thein Nyunt tried three times to amend laws, including the Penal Code and Child Law, to require the death penalty in cases of child rape, but failed each time. He lost in the 2015 general election but has continued to lobby for the changes.

“The reason I contest elections is to put child rapists to death,” he told Frontier. “I will continue to work toward this until I die.”

But, like his attempts before her, Khin Saw Wai’s proposal also failed. During the ensuing parliamentary debate, the Supreme Court of the Union argued that a mandatory death sentence for child rape could risk encouraging perpetrators to murder their victims in an attempt to destroy the evidence. NLD MPs, who were instrumental in defeating the proposal, also argued that capital punishment was not the most effective deterrent.

There was no specific law on child rape when Khin Saw Wai tabled the proposal; section 376 of the Penal Code provided only for a maximum penalty of 20 years’ imprisonment for rape in general. But in March 2019, the section was amended to define a crime against a woman aged under 16 as a crime against a child, and to make the rape of a girl aged under 12 liable to either life imprisonment or a 20-year prison sentence.

Under section 302 of the Penal Code, the death penalty can be imposed in cases where rape victims are murdered. It states that anyone who commits murder in the course of committing an offence that is itself punishable by a prison term of seven years or more “shall be punished with death”.

“Some still think that the death penalty is the best revenge, especially when emotions run high, as in these cases,” said Aung Myo Min.

A hiatus in hangings

It is widely believed that the last convict to be executed in Myanmar was political prisoner Salai Tin Maung Oo, a young Chin man who took part in student protests over the funeral of former United Nations secretary-general U Thant in December 1974. After the protest, Tin Maung went into hiding for a couple years, before being arrested on March 22, 1976 and hanged at Yangon’s Insein Prison the following June. But, says U Khin Maung Myint, a retired warden of Mandalay’s Obo Prison, the last two judicial executions were carried out in the spring of 1988, when two men were hanged for murder at prisons in Mandalay and Bago regions.

“I was able to witness the execution of a young man named Win Myint at Mandalay Prison in late March of that year,” he told Frontier.

While the forms of execution vary around the world – electrocution, lethal injection, beheading, shooting – in Myanmar, by law, all death penalties are carried out by hanging.

Khin Maung Myint said another death row execution took place that May at Taungoo Prison, in Bago Region.

Since then, anytime a judge has ordered the ultimate punishment, the convict has later had their sentence commuted by presidential pardon while on death row.

It is unclear why this is. Some attribute it to the lengthy legal process surrounding state executions, while others say that, in the absence of a law abolishing capital punishment, it has depended on the attitude of individual government leaders.

Courts in Myanmar impose the death penalty for such crimes as high treason, treason, rebellion, drug trafficking and human trafficking, but the Jail Manual stipulates that the execution cannot be carried out until confirmed by the Supreme Court of the Union, the nation’s highest court. A person sentenced by a district court has seven days to file an appeal to a state or regional court; if the appeal is rejected, the prisoner can appeal to the Supreme Court. If the Supreme Court does not commute the sentence, the prisoner has exhausted all appellate avenues for mercy but still has the right to submit a special petition for clemency to the president within seven days of receiving the court’s decision. Article 54 of the Penal Code allows the president to commute any death sentence with or without the offender’s consent. “In my experience, just about every death row inmate sends a petition letter to the head of state,” said Khin Maung Myint.

Even if this final appeal is rejected, the prison warden cannot proceed with the hanging until receiving an order to do so from the president, according to Section 634(4) of the Prison Manual. Myanmar’s previous president U Thein Sein, who served from 2011 to 2016, never signed off on a single execution – a trend continued by former NLD president U Htin Kyaw and incumbent U Win Myint, who become president in 2018 after the former’s resignation.

“The law needs to change so that the sentence is carried out whether or not the president responds,” said Thein Nyunt, the child rights activist. “Death sentences should not be delayed by all these appeals to the president.”

U Aung Myo Kyaw, who directs the Yangon office of the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, believes the refusal to sign off on executions may be due to the government’s scepticism about the judicial process. “Perhaps they are worried about taking responsibility for executions that should never have been carried out,” he said. “There are examples of people, especially political activists, who were wrongly executed under the military regime.”

Khin Maung Myint, the retired warden, said his Mandalay prison accepted more death row prisoners after the 1988 uprising than at any time in the 23 years he worked in Myanmar’s prisons. “There were 51 death row inmates – 19 convicted by civilian courts and the rest by military tribunals,” he said. The law requires death row inmates have their own cell, but there were so many at the time that he had to house five or six together in each cell.

Figures on the number of death sentences handed down each year by the courts, and the number of death row prisoners who have had their sentence commuted as a result of a presidential pardon, are elusive. U Ye Yint Naing, Prisons Department deputy director, said there are about 100 inmates on death row in prisons throughout the country but could not give a precise figure “because we don’t maintain a separate list for death row prisoners”, he said.

Former Myanmar National Human Rights Commission member Yu Lwin Aung said figures as of November 2019 showed 82 prisoners on death row – nearly 95 percent of whom were men. His figures also show that 721 prisoners were serving 20-year life sentences and 254 inmates were serving longer sentences after having death sentences commuted, he said.

The status quo

Human rights campaigners, including Aung Myo Win of Equality Myanmar, continue to urge the government to sign the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1966 and has been signed by more than 170 countries, and Article 6 of which reads: “Every human being has the inherent right to life.” In September 2019, the Hluttaw voted down a proposal by an NLD MP to sign on.

“Although the proposal was not approved, the Minister of International Cooperation said the government would continue to work toward signing it,” said Aung Myo Min. “We will raise the issue again in the new Hluttaw.”

“We understand that it will take time to abolish the death penalty in Myanmar, and plan to conduct awareness programmes to educate people about why capital punishment needs to be ended.”

There has been little public debate on the subject since the NLD took office in early 2016, but it was the focus of a closed-door meeting in Nay Pyi Taw in late 2017. The abolitionist AAPP was invited to the meeting as one of several civil society groups to discuss the issue with government officials.

“The meeting was arranged by the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission, which wanted to hear what other groups have to say about abolishing the death penalty, but most officials were opposed to its complete abolition,” Aung Myo Kyaw said.

The current chair of the MNHRC, U Hla Myint, said the commission is not engaged in any discussions right now with the government, the United Nations or any international organisations on abolishing the death penalty. “The death penalty is legal but not practiced in Myanmar right now, and I believe that if we stick to this, it will be beneficial for Myanmar, which faces various allegations of human rights abuses,” he said, adding that he speaks only for himself and not the commission as a whole.

In a statement on October 10 last year to mark the 18th World Day Against the Death Penalty, the European Union in Myanmar issued a statement that recognised the country as being “abolitionist in practice”.

“This is undoubtedly significant progress that we wish to commend,” the statement said. It urged all stakeholders, within the government and the Hluttaw, to take the next step and formally abolish capital punishment.

“Such a landmark decision would strengthen the essential path towards democratization and remove a legislative barrier to the further advancement of the rule of law, of the justice system and of the respect of human rights for everybody,” the statement said.

For Aung Myo Kyaw of the AAPP, this is the only acceptable solution.

“If the death penalty is not completely abolished, even if it’s never carried out, it still can be carried out at any time,” he added. “That should never happen under a democratic government.”