Myanmar’s child immunisation programmes are failing to reach children across the country, particularly in conflict zones. Health experts warn the results could be devastating.

By FRONTIER

Myanmar’s ravaged borderlands are facing outbreaks of preventable diseases following plummeting child immunisation numbers. The military’s post-coup crackdown on armed resistance and a strike by healthcare workers participating in the Civil Disobedience Movement are hampering the implementation of once routine immunisation programmes.

In Kayin State, the annual immunisation programmes once conducted by the Ministry of Health in cooperation with ethnic health organisations in many villages have stopped altogether.

Repeated airstrikes and heavy artillery fire have forced locals in districts across Kayin State to flee – especially in Hpapun District (known locally as Mutraw District) where many villages were targeted. As a result, Naw Eh Hsar*, a health worker from a local ethnic health service, confirmed to Frontier in late April that routine immunisations for children could no longer be carried out.

The lack of immunisations in Kayin State has had an immediate effect, with disease multiplying in congested camps for internally displaced people. The Karen Peace and Support Network estimates there are around 82,000 IDPs in Hpapun and over 36,000 IDPs in Kawkareik Districts. Last year there were outbreaks of malaria, chickenpox and diarrhoea in these areas. Eh Hsar blames the lack of vaccinations for chickenpox and rotavirus as the cause of the last two of these outbreaks, with conflict areas hit the hardest.

A number of frontline Karen healthcare workers confirmed that malaria, diarrhoea and other infectious respiratory diseases, including COVID-19, are still spreading rapidly throughout Hpapun, Kawkareik and along the Thai-Myanmar border.

“The most common outbreak areas in Kayin State are along the border with Hpapun and Kawkareik Districts,” Eh Hsar said. “These diseases are found in almost all war-torn villages… Routine immunisation could not be carried out here because ethnic displaced people from IDP camps are moving from one place to another every week or two.”

Health experts warned that as routine immunisation programmes struggle to reach parts of the country, the likely outcome is a rise in preventable disease.

“Overall, routine immunisation has collapsed,” said Dr Kyaw Swar Win*, a health expert in immunisation who works at an international health organisation.

“The leadership and human resources have changed,” he said, referring to health department staff at the national level. “That’s really alarming. It’s going downhill.”

Attacks on the health system itself have further compounded the issue, with 128 health facilities attacked and 30 health workers killed since the junta seized power, according to Physicians for Human Rights. Many people now avoid going near hospitals and clinics under the junta’s control.

Dwindling coverage

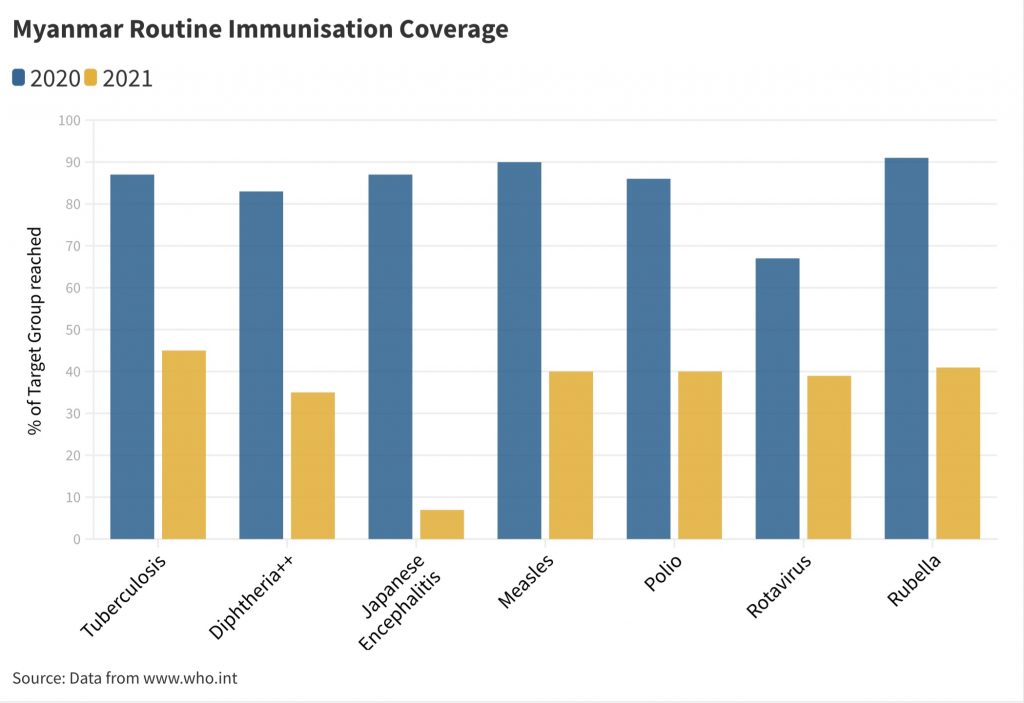

Vaccine coverage data from before the coup, up to and including 2020, shows the vast majority of children in Myanmar were receiving their routine immunisations for diseases including tuberculosis, diphtheria, measles, rubella and polio. Most vaccines reached over 80 percent of the target group, and many, including the measles vaccine, reached 90pc or more, according to both government and WHO data.

The 2021 figures tell a different story however, with vaccination rates plummeting to staggering lows not seen in Myanmar since the 1980s. Although the figures are yet to be finalised by WHO and UNICEF, sources told Frontier the 2021 data is unlikely to vary significantly from the currently published official figures.

Worryingly, infectious diseases such as tuberculosis risk re-emergence with coverage rates halving from 87pc to 45pc in one year; full courses of vaccinations for measles dropped from 90pc to 40pc; and polio from 86pc to 40pc of the target group. All current vaccination data reported by the health ministry on WHO’s dashboard tells the story of a sharp decline in immunisation service delivery.

The responsibility for the national rollout of childhood immunisation programmes across the country is shared by multiple agencies. In more normal times, the Ministry of Health leads the efforts, in partnership with three international organisations: UNICEF supports the delivery, the World Health Organisation provides technical assistance, and the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI), established by the Gates Foundation, provides 74pc of the required funding.

UNICEF forewarned the public earlier this year when they released their 2021 Annual Report, which gave a wide estimate of 40-80pc of children in Myanmar being unable to access immunisation services last year. On April 29, they posted on Facebook that with routine immunisation against life-threatening diseases currently at low rates in Myanmar, there is a serious risk of disease outbreaks.

Despite their responsibility for delivering large parts of the national vaccination programme, UNICEF, WHO and GAVI all declined to provide an interview on these issues to Frontier. A WHO communications consultant noted that reporting comprehensiveness and data reliability on immunisation programmes had been “compromised by recent events”.

They are expected to finalise vaccination data for 2021 in July. However, a completely accurate data picture of immunisation since the coup may never emerge, given the chaos and instability around the country and the junta’s weak grip on public health programmes.

Regardless, the junta is already aware of the failures of the immunisation programme to some extent. Dr Than Naing Soe, spokesperson for the junta’s health ministry, told Frontier that although hospital-based vaccinations continued to be effective, coverage at the community level is limited.

“There are some places where vaccination is not available,” he said. Than Naing Soe did not reply to further questions about the junta’s plans to address the drop in vaccination numbers.

The cost of the vaccination program is likely another headache for the junta. Back in 2020, former Minister of Health and Sport under the National League for Democracy government Dr Myint Htwe spoke about the costs of the programme at a training ceremony in Nay Pyi Taw. The former minister said that the cost of vaccinating a child with the recommended 12 vaccines is about US$40, with 26pc of the cost funded by the state and 74pc from GAVI.

That means funding of at least $10 million a year from GAVI, who have also provided large grants to improve the health system. The health ministry is supposed to take over responsibility for 100pc of the costs of an expanded programme of immunisation in 2025, as per deals that were struck prior to the coup.

Further complicating matters, GAVI may be withdrawing their support. Two sources with inside knowledge told Frontier that GAVI has suspended all financial support regarding vaccination to the junta’s health ministry since the military coup. GAVI did not confirm or deny this to Frontier.

Healthcare workers take a stand

The rollout of vaccinations has also been critically hampered by the number of healthcare workers who have reportedly joined the Civil Disobedience Movement and stopped working.

At the local level, child vaccinations are delivered by local frontline workers including healthcare workers, medical officers and township community health nurses. They all work under the auspices of the Expanded Programme on Immunisation, consisting of teams at the regional and state level coordinated by the health ministry in Nay Pyi Taw. Many of the health workers delivering the EPI have walked off the job in protest of the junta.

Dr Htet Myat Tun* is a health expert who used to work on the EPI who has joined the CDM. He told Frontier that 90pc of health staff working for the EPI had joined the CDM since the coup, and the junta’s health ministry is now struggling to cope. No public data has been released.

One of those who joined the CDM was Dr Htar Htar Lin, the former director and programme manager of the Ministry of Health division responsible for the EPI. Security forces arrested Htar Htar Lin along with her husband and young children on June 10 last year in Yangon for her defiance of the regime. The military charged her with corruption, misuse of public funds, and incitement of anti-junta sentiment.

Htar Htar Lin was sentenced to three years in prison with labour under section 56 of the Anti-Corruption Law, which was announced by military mouthpieces MRTV and Myawady on April 20 of this year. The Anti-Corruption Commission claimed the state had lost over K161 million (US$87,000) due to her “non-compliance” while supervising a large GAVI-funded health systems strengthening grant, in which she oversaw procurement of vaccines.

“The military is using the vaccination programme as a tool to persuade people and to end the Civil Disobedience Movement,” Htar Htar Lin wrote to colleagues in a Signal message announcing her resignation. “All central and Region/State EPI focal [people] are with [the] CDM. They were refusing to conduct the vaccination.”

“Our vaccine is not a tool to make our country go under the footsteps of the military,” she added.

The message was later leaked to the media and confirmed as authentic to Frontier by multiple health ministry sources.

Dr Hlaing Win Aung*, another expert on immunisation programmes who spoke with Frontier on condition of anonymity, said that the health ministry’s National Surveillance System has also collapsed in the aftermath of the coup.

The National Surveillance System is a nationwide initiative for states and regions to share health data and information with the central government. Its purpose is to monitor, control and prevent the occurrence and spread of reportable diseases that are usually monitored by the government.

“Currently, we have almost no information and data about vaccine preventable disease conditions from healthcare workers on the ground related to routine immunisation. Health departments can’t function anymore because the health staff joined in the CDM,” Hlaing Win Aung said.

“We understand that this data, the facts and figures, are controlled not only by the Ministry of Health, but also by the military administration,” he added.

The National Surveillance System also monitors and reports on COVID-19 cases. The failure of the system may also be a factor in the current very low numbers of cases being reported in Myanmar.

Conflict zones see spike in disease

Health experts and healthcare workers from ethnic health organisations told Frontier that before the coup, these organisations had been cooperating on routine immunisation with healthcare workers from the health ministry in areas controlled by ethnic armed organisations. Since the coup, they said, vaccination programmes were no longer available in conflict areas controlled by EAOs.

“If children are to be vaccinated in ethnic and conflict areas, individual information … must be reported to the military council. It contains sensitive personal information,” Hlaing Win Aung said.

“These are conditions that make it impossible in ethnic health groups and conflict areas to fully comply with routine immunisation, and without such agreements, vaccinations will not be readily available in those areas,” he added.

On their own, ethnic health organisations are struggling to fill the gaps. UN OCHA’s Humanitarian Programme Cycle 2022 report issued in December last year said that the private sector, NGOs and ethnic health organisations cannot fully replace critical public health services such as routine immunisation.

When Frontier interviewed 10 people in EAO areas from Kayin, Kayah and Chin states in April regarding routine immunisation programmes, all responded that vaccinations for children have stopped since the military coup.

A medical doctor from Kayah’s capital Loikaw, Dr Than Htike*, confirmed that the total number of fully vaccinated children had massively declined.

“Most children are not vaccinated. I think less than half the number of children getting vaccinations before the coup now go to Loikaw hospital to receive routine immunisation,” he said.

Dr Zaw Wai Soe, Minister of Health and Education from the National Unity Government, urged international organisations to work with the NUG to ensure that aid reached the whole country.

“Forty-five percent of the whole country is now occupied by revolutionary forces and ethnic armed groups,” he claimed at a recent forum organised by the NUG’s health ministry on April 20. The extent of control by these groups can’t be substantiated by Frontier.

“I would like to say that if there are international organisations which want to support and provide healthcare aid for the whole country, they can’t communicate with the [junta] only. They must communicate with the NUG,” Zaw Wai Soe said.

Dr Kyaw Swar Win, immunisation expert, said that the coup had erased the decades of hard-won improvements in the nation’s vaccination programmes.

“The collapsing health system after the military coup of 2021 is worse than the situation in 1988,” he said. “It will take many years for the health system to recover.”

*Some people’s names have been changed at their request due to personal safety fears.

A previous version of this story stated that tuberculosis vaccination rates dropped from 91pc to 45pc after the coup. The rate was 91pc in 2019, 87pc in 2020 and 45pc in 2021.