Time is running out for an international moratorium on new fossil-fuel power plants. Myanmar needs to take notice.

By DAVID FULLBROOK | FRONTIER

“…if [Asia] implements the coal-based plans right now, I think we are finished,” Mr Jim Yong Kim, the World Bank president, told the Climate Action Summit in Washington in early May.

Kim’s concerns about plans by China, India, Indonesia and Vietnam to build three-quarters of the world’s new coal-burning power plants by 2020 were widely reported. His frank departure from prepared remarks coincidentally followed research indicating that the world is on the brink of mean global warming beyond 2 degrees Celsius.

In April, Ms Lindee Wong and colleagues at Ecofys, an energy, renewable energy and climate change consultancy in the Netherlands, found that new, high-efficiency, low-emissions coal power plants — even with costly capture and storage technology to pump greenhouse-gas emissions deep underground — would push global warming beyond 2°C.

The findings are cold comfort. In February, an Oxford University research team led by Mr Alexander Pfeiffer concluded that for an even chance of staying below 2°C, power plants built after 2017 must be zero carbon.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

In other words, if coal or gas-fired power plants are built after 2017 they must capture and store carbon emissions, an immature process not yet ready for thousands of planned fossil-fuel power plants.

If new power plants do not emit greenhouse gases global warming may stay below 2°C. Locally, however, in many places warming will exceed 2°C, bringing more of the soaring temperatures and drought experienced throughout much of South and Southeast Asia in 2016. Beyond 2°C, much more stress is expected for food, water and security, research has shown.

How the world responds to that risk has great implications for policy, planning and investment in energy, the primary source of industrial greenhouse-gas emissions. The question of fossil fuels – specifically coal – and the 2°C goal poses the first litmus test for the values, ambitions and commitments of last December’s Paris climate conference.

A global moratorium commencing in 2017 on new fossil-fuel power plants without carbon-capture technology is an option. It would have to be accompanied by grants and cheap international loans to help countries that cancel fossil-fuel power plants to rapidly develop energy efficiency, solar and wind.

Technically that’s a challenge, but it’s doable for two reasons. One, China and India have proved that solar and wind technology can be built quickly at scale. Two, the potential for industrial mobilisation similar to that seen during World War II. Carbon capture and nuclear power could play a larger role if costs fall.

Politically a moratorium looks like a tall order, but when the stakes are high, states sometimes act decisively. The global bailout of banks in 2008 is one example. Another is the Montreal Protocol to protect the ozone layer, which was agreed two years after the discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole in 1985.

Remarkably, a moratorium and decarbonisation of energy could quickly pay for itself. Co-benefits for health, prosperity and security may exceed the costs of scrapping fossil fuels, according to the Global Commission for Economy and Climate. International Monetary Fund analysts have calculated that the cost of harm caused by fossil fuels in 2014 was nearly 50 times more than subsidies for renewable energy.

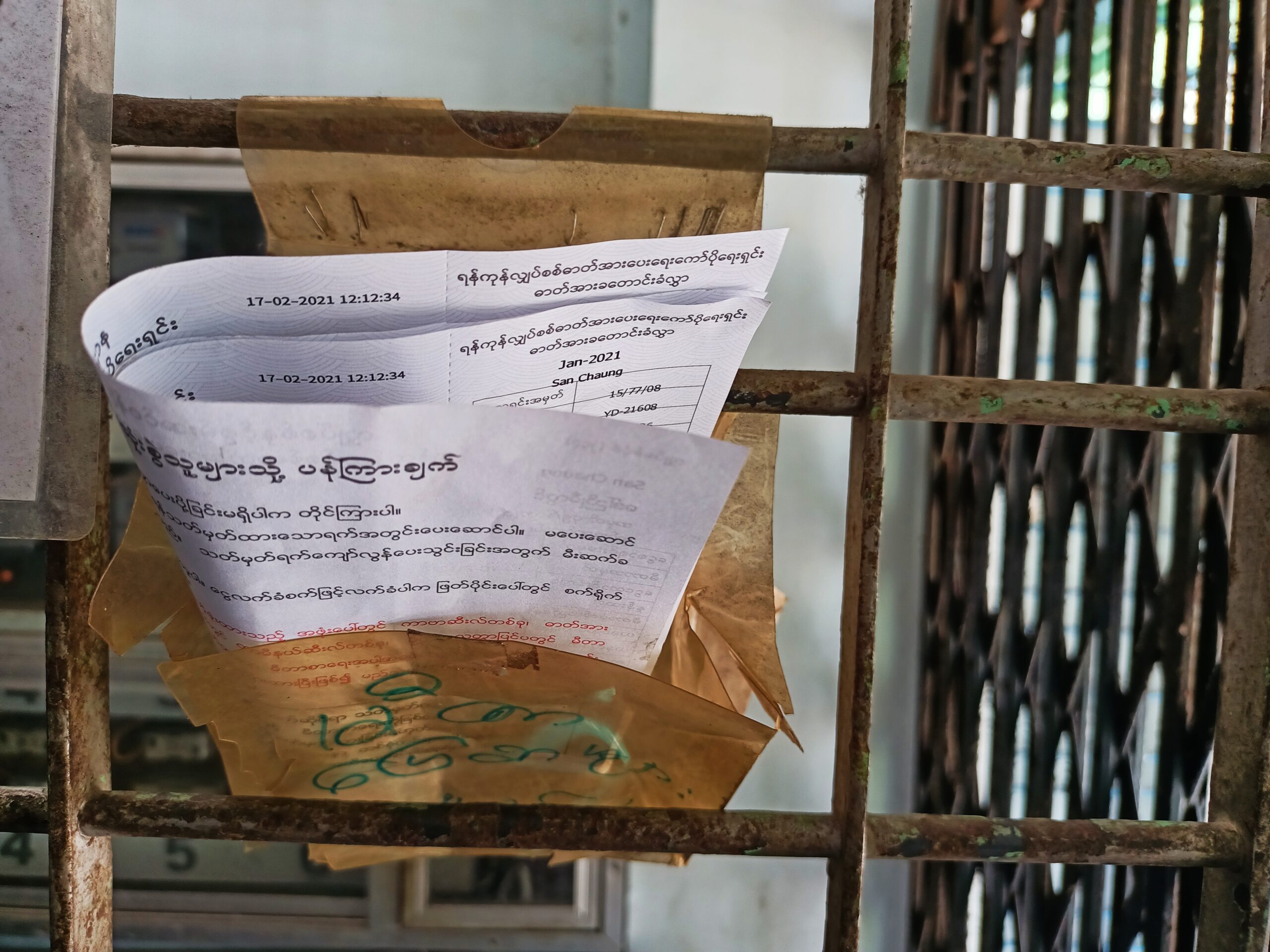

myanmar_power_lines_afp.jpg

A view of Myaung Ta Gar power station in northern Yangon. (Ye Aung Thu / AFP)

That year, direct subsidies for fossil fuels were almost five times those for renewable energy, the International Energy Agency estimated.

On the other hand, if a moratorium remains out of reach, our prospects depend on how well we adapt to a warmer world, an endeavour clouded by uncertainty. The interdependencies and feedbacks among climate and food-providing ecosystems, societies and security are simply too complex and dynamic. Adaptation becomes harder as the world becomes warmer.

That poses a growing threat to conventional electricity generation. Long-held design assumptions must be revisited to ensure electricity infrastructure performs as we need in the face of more droughts and storms like Cyclone Nargis, which hit Myanmar in 2008.

Engineering must pay greater attention to social stress, rising seas and, most critically, competition for water. Adapting conventional approaches generally raises costs, affecting risk and return for investors committing to decades-long projects such as electricity infrastructure.

The question facing policy makers, planners and investors in Myanmar is what to do while waiting to see how the world responds in 2017.

Second-guessing global policy over the next few years while trying to figure out the best way to adapt new infrastructure may in any case be something of a fool’s errand. Instead, planners and investors could reduce risk, as well as reducing social impacts, through design, by fundamentally rethinking electricity systems around the technological and environmental conditions of the 21st century.

It is a golden opportunity for Myanmar, where so much electricity infrastructure is yet to be built. This is seemingly recognised in the National League for Democracy’s 2015 election manifesto.

Technologies and principles are already well understood and being applied in rich and poor countries worldwide. Energy efficiency, batteries, solar modules and wind turbines are less vulnerable to climate change impacts and policy than conventional alternatives. Costs for renewable-energy technologies are falling fast. Meanwhile, the avoided health and environmental impacts will ensure people in Myanmar are better off with renewables.

The key to luring investment is clear long-term policy. Get that right soon and whether or not a moratorium comes to pass Myanmar will be on the way to climate-resilient, accessible and affordable electricity.