Frontier’s photography team reflect on election day, from the trepidation of entering a large crowd to getting yelled at by polling staff and the bittersweet experience of an image going viral without any credit.

By FRONTIER

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe, photojournalist

I had registered with two Frontier journalists to cover Yangon’s Southern District. Our main interest was whether voters in Dala Township, a sprawling, lower-middle class suburb across the Yangon River from downtown Yangon, would be able to vote safely given COVID-19. We set off early and took a boat there, arriving at the polling station in Myo Ma 4 ward before 5:30am. Already there were more than 20 people waiting. At 6am exactly, the gates opened. As soon as we entered, a teacher wearing level 2 PPE sprayed our hands. Election day is always a long one for polling staff – who are mostly teachers – but this year they also had to focus on COVID-19 prevention, which meant they were much busier than usual.

We then checked in at other polling stations in Dala. Some were crowded with voters, while others were quiet. At the 11/14 ward station, I noticed a sign warning people not to take photos or videos. As I had accreditation, I ignored it. A teacher then shouted at me, and dismissed my explanations. Rather than argue, we moved on to another station where they were more familiar with the rules.

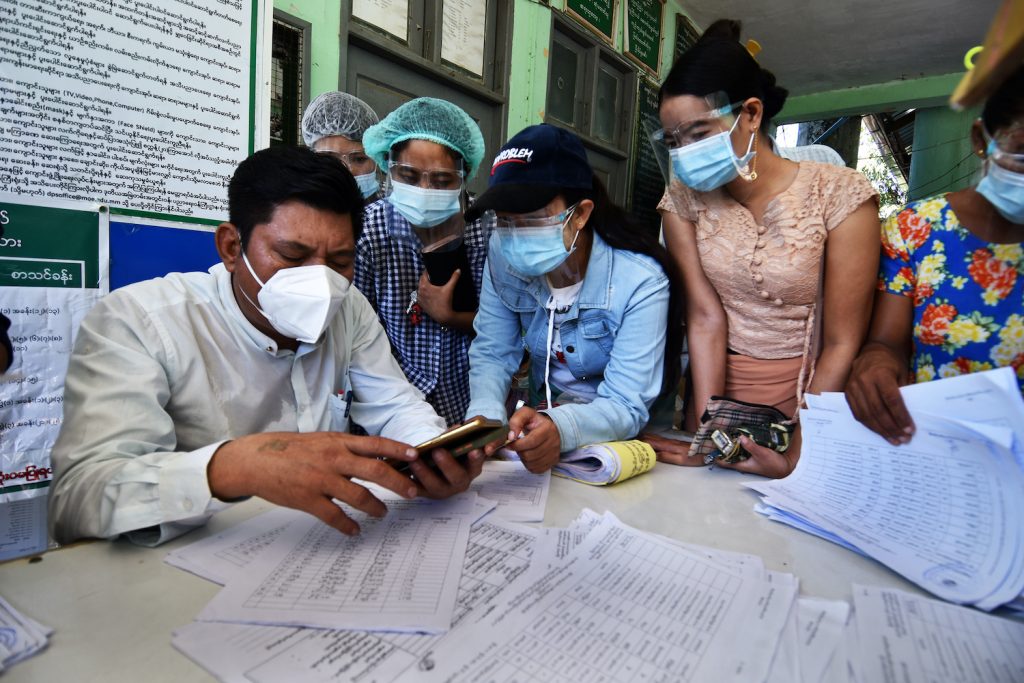

We could sense right away that the mood at the Kyan Sitt Thar ward polling centre was different. The ward has a large population, and there were 11,000 voters registered to cast their ballot at this one station. We saw hundreds of people jostling in front of the polling centre, and there were similarly chaotic scenes inside, with no social distancing whatsoever.

The huge numbers of voters eligible to cast their vote at the polling station in Kyan Sitt Thar ward in Dala made social distancing impossible. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

(Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Honestly, I was hesitant to enter the crowd even though I was wearing gloves, an N95 mask and a hair covering. But I knew there were no other photographers around. “If I don’t shoot this, I don’t know who will,” I thought to myself. I went into the crowd alone, while my colleagues conducted interviews with people in the scrum in front of the entrance. The only improvement inside the compound was that people were wearing face shields that they’d been given by volunteers upon entering. There was no social distancing, and lots of pushing. It was chaotic. Polling station officers were trying to take temperatures among the crowd, and some people were taking off their masks because of the heat. Again I was yelled at for taking photos, and again I just moved on to another room in the polling centre.

We returned to Kyan Sitt Thar in the evening to watch vote counting. When we arrived at the polling station there were still hundreds of people waiting in the compound to vote. A man was shouting from a loudspeaker that the last time to vote was 4pm. After that, some polling station officers closed the doors and windows of the polling station rooms to count votes.

We weren’t invited inside. We were confused: according to the Myanmar Press Council, accredited media was allowed to observe vote counting. We knocked on the door and they ignored us; we looked in through the window and they ignored us. We continued knocking and eventually the head of the polling station came to meet us. When we explained we had accreditation, he let us enter but said we couldn’t take photos. We protested and he called the head of the Dala Township sub-commission. My colleague said to him, “We know the rules. We can’t take photos in the room while people are voting. But we can stay and take photos while votes are being counted. We did it back in 2015, too.” We finally got the green light, but we could tell it unsettled some of the teachers. We could hear them saying things like, “During our training we were never told anything about the media being allowed in the room while we’re counting votes.” Back during the 2015 election, we faced a lot of misunderstandings like this with polling station officials. I thought it would be better this time, but it seems things haven’t changed that much.

Thuya Zaw, photojournalist

My first priority on election day was to photograph voters at a polling station set up inside a Chinese temple on Anawrahta Road in Latha Township. Almost immediately I encountered trouble. “You don’t have permission to be in this polling station compound,” the chief of the polling station shouted at me. My first reaction was indignant: I was wearing a media badge issued by the Union Election Commission to accredited media, and I wasn’t disturbing anyone who was voting. But after noticing the glares coming at me from around the polling station, I decided to cut my losses – I had a lot of places to visit on election day and I didn’t want to waste time arguing with the head of a polling station who clearly didn’t know the rules.

I headed over to a station for military personnel in Botahtaung Township. Suddenly, I saw a woman walking towards the polling station to vote while carrying a young baby. She was wearing protective equipment and had covered her baby with a linen cloth. My first thought was that she’d come to cast a vote for the future of her baby, and I quickly took a photo of her as she approached.

Later that day I visited a polling station in Mayangone Township’s No 10 ward. People who were waiting outside of the polling station weren’t following social distancing rules and I pulled out my camera to take a photo. Suddenly the chief of the polling station emerged and told me to stop taking photos because they were relatives of military personnel. I told him that I had a right to take photos outside the polling station. I called the Mayangone township election sub-commission to complain, and it actually worked: they called the head of the station and ordered him to let me take photos. He then invited me inside the station.

On election night, I found that my photo of the woman walking to vote with her baby had gone viral. For many people the photo seemed to encapsulate the bravery of everyone who had gone out to vote despite COVID-19. Within a few days, someone had even turned the photo into an illustration that was also being shared online.

Normally, having your work shared so widely would be an incredible experience, but this was bittersweet: while it was gratifying to see so many people connecting with my work, it was being shared without any credit to me or Frontier. We had posted the photo on the Frontier Facebook page on election day, and it seems someone had simply saved the image and posted it on their Facebook without any credit. By the time it popped up in my news feed, people were writing “Credit: original owner”, as has become the custom in Myanmar when sharing photos of unknown origin. People do it without thinking about the effort the photographer had to put in to take the photo. It was very sad and disappointing to see my work being misused in this way.

Election commission staff prepare to conduct advance voting for COVID-19 patients at the AYA treatment centre in Yangon on November 6. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

A COVID-19 patient casts an advance vote. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

The AYA centre was the only facility for COVID-19 patients that granted access to photojournalists. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

Hkun Lat, photojournalist

On November 6, the Union Election Commission was working at COVID-19 quarantine centres to enable patients to cast an advance vote. In the morning I’d been photographing parties taking down their election signboards, as November 7 was to be a “silent day” before the public went to vote. In the afternoon I went to the AYA COVID-19 treatment center in Thingangyun Township to photograph patients casting advance votes. There was already a crowd of photographers there because the other centres didn’t allow any photos of voting, citing security reasons. The staff gave us level 2 PPE – a mask, hair cover, gloves and gown – which we put on before entering. After we entered, UEC officers wearing PPE came out, and one of them held a ballot box. They prepared tables and called voters one by one. The area we’d been assigned to was a bit far from where they were casting votes, but we could see them clear enough. UEC officers were helping patients cast votes, and other voters were watching on. After one woman voted, everyone clapped and cheered. A few minutes later we were told we had to leave.

When November 8 arrived, it was a big day for everyone. The highlight for me came after the polling stations closed, when NLD supporters began celebrating in front of the head office before results had even been released. When they began gathering, I was still watching votes being counted in a polling station in South Okkalapa, but I got over to Shwegonedine as soon as I could. I was surprised to see such a large crowd of people – they seemed totally unafraid of COVID-19. They sang, cheered and shouted, some even without masks. I wasn’t so confident. I stayed there for a few minutes to photograph them and then made my escape, leaving the cheering and drumming behind.

Hlaing Tharyar residents queue on a wooden bridge to vote at a polling centre. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Polling station staff in PPE walk along a corridor at Hlaing Tharyar’s BEHS 14 on election day. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Steve Tickner, photo editor

I spent the morning at a polling centre inside Basic Education High School 14 in Hlaing Tharyar Township, a huge industrial suburb on the western outskirts of Yangon. This polling centre was unusually large, with 31 classrooms set aside as polling stations. Many thousands of voters passed through during the day. Prior to the election there had been a lot of discussion about whether the vote could go ahead safely given the prevalence of COVID-19 in Yangon. We saw an ample supply of PPE in the form of masks, shields and hand gel, but at this particular polling centre there was an almost complete absence of social distancing. The huge numbers of voters and long queues made it almost impossible.

The mood was generally positive, but as the morning progressed a growing number of people began complaining about not being on the voter list. They waited hours to try and get the chance to vote, but were eventually denied (you can watch Doh Athan’s fantastic video about these voters here). Despite the problems, polling station officials in Hlaing Tharyar were quite open and cooperative with media, allowing us to take photos inside the stations where people were casting their votes.

After midday we visited a polling station in Mingaladon Township very close to a military base. Here, the attitude was completely different. I was challenged by the person who was apparently in charge of the station, refused admission and told to stay outside. I argued that I had a right to enter the polling station as I was an accredited photographer. My colleague joined in to argue my case and while that discussion continued, I simply walked into the polling station and began taking photos. Nobody else said anything.

Inside, I met a foreigner who identified himself as an observer with the French embassy in Yangon. He was very interested in my impressions and I explained the difference between this station and the one I’d seen in Hlaing Tharyar. I later learned the observer was Mr Christian Lechervy, the French ambassador to Myanmar.

In the afternoon we returned to BEHS 14 to watch vote counting, which was orderly and transparent. Overall, I was impressed with the demeanour of the voters, some of whom had to wait a long time to cast their ballot, but the errors on the voter list had left many deeply disappointed. I wasn’t at all surprised to run into officials with a poor understanding of the media’s role in the election, though.