The government has finally closed the door on the import of used vehicles from Japan, but many are concerned that the policy changes have put cars out of reach for all but the wealthiest households.

By KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

PRICES FOR used cars have jumped 10 to 20 percent since the Motor Vehicle Import Supervisory Committee released its 2018 policy on October 16, and increased restrictions on used-car imports.

But the latest price jump continues a trend that began several years ago, when U Thein Sein’s government began tightening import rules in response to concerns about worsening traffic congestion.

Many models are at a 20 to 30 percent premium on what they were selling for in 2014-15, while some have as much as doubled in price. The weakening currency has been a factor – the increases in US dollar terms are less dramatic – but the main driver has been policy changes.

These changes are designed to reduce the trade deficit, improve safety, promote sales of new cars – particularly those produced locally – and address concerns about traffic congestion. But some have expressed dismay that entry-level passenger cars are now an unaffordable dream for all but the wealthiest people in Myanmar.

Recent changes

The Motor Vehicle Import Supervisory Committee’s two-page policy announcement last month brought some important changes.

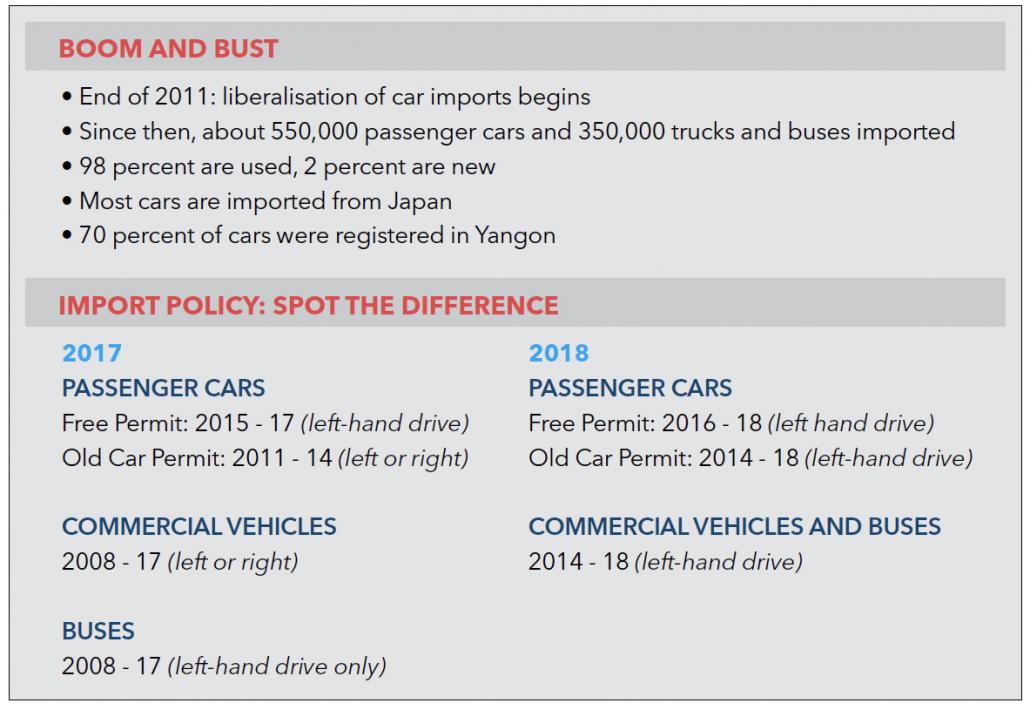

The new policy further restricts the age and type of used vehicles that can be imported. From January 1, only left-hand drive vehicles manufactured since 2014 – and in some cases 2016 – will be eligible.

There are two main types of import permit: free permit and old car permit.

The first – free permit – is designed for personal use. Any individual who can show they have paid income tax is eligible to import a car. Under the 2017 policy, left-hand drive cars manufactured from January 1, 2015, could be imported; next year, vehicles must be left-hand drive and manufactured since 2016. Tax rates depend on the engine size and are designed to encourage the import of small cars.

The second system requires what’s known as a “slip” – a permit received after handing in a car deemed old or unsafe. In 2017, a slip – which sells for around K13 million – could be used to import a left or right-hand drive car made between 2011 and 2014. However, next year the slip can only be used to import a left-hand drive vehicle made since January 1, 2014.

The import rules have also been tightened for commercial vehicles and buses.

While the changes have been welcomed for finally addressing a major safety issue – the proliferation of right-hand-drive cars in a country that drives on the right side of the road – there is widespread dissatisfaction at the impact on prices, particularly the high levels of tax levied by the government.

The present situation is certainly a departure from when the Thein Sein government dramatically liberalised car imports in 2011 and 2012. Prices plummeted and small-engine, late-model vehicles were soon available for less than K10 million.

The Motor Vehicle Import Supervisory Committee is chaired by Minister for Commerce U Than Myint. The committee could not be reached for comment, as its only representative allowed to talk to the media was travelling overseas last week.

A boon for local manufacturing

One of the major aims of the vehicle import policy is to encourage the development of local industry, particularly vehicle assembly.

The government offers significant tax benefits for cars assembled in Myanmar under the semi-knocked-down (SKD) classification, whereby some of the parts are imported separately and assembled.

The tax benefits and tightening of imports make new SKD vehicle prices competitive with used cars brought in from Japan; a new, locally assembled small car can be bought for as little as K22 million, for example. This is less than a 2013 model Honda Fit, for which you can expect to pay around K24 million.

In contrast, new cars that are imported as finished products are significantly more expensive.

New Ford vehicles have been available in Myanmar since 2013 but earlier this year its local partner received permission to commence SKD production in East Dagon Industrial Zone. In July, Thailand’s RMA Group and Myanmar’s Capital Manufacturing Limited opened the facility, which can assemble up to 6,000 vehicles a year.

Ko Okkar, a communications manager at Ford Myanmar, said the locally assembled models were dramatically cheaper than if they had been imported as finished products.

One model, the Ford Everest (Titanium), was priced at $89,900 when it was imported complete. Since being assembled locally, Ford has been able to drop the price to $67,000.

The lower prices have had some impact. Ford was selling 25 to 40 vehicles a month in early 2016, but now the number is 180 to 220, Okkar said.

“If the government can reduce the taxes that we have to pay, our vehicle prices will drop even further,” he said.

Another issue that makes SKD vehicles more attractive is licensing. Imported cars – even new vehicles bought at a showroom – cannot be registered in Yangon, except for those brought in to replace an old car that was registered in Yangon.

In contrast, locally assembled vehicles can be registered in Yangon.

Hidden costs

But the industry still faces a number of challenges. A range of factors conspires to push up production costs, including high land prices, and poor electricity supply and infrastructure.

Factories are also producing relatively few cars compared to facilities in neighbouring countries, so have higher production costs.

Taxes are another issue. They must be paid when the car is produced rather than sold, which places a heavy up-front burden on manufacturers.

U Aye Tun is a director at Yangon Suzuki and chairman of United Diamond Motor, the local partner of Nissan. Both companies sell new vehicles partially assembled in Myanmar.

He said carmakers in Myanmar faced higher costs than in most countries and this was depressing demand for new vehicles, as producers could not drop their prices any lower.

Under present conditions, neither manufacturers nor used-car dealers are able to meet the needs of the market, where buyers want more affordable passenger cars.

A Kia car on display at an exhibition at Yangon’s Tatmadaw Hall. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

Owning a vehicle is a middle-class dream, he said, and should not be the reserve of a privileged elite.

“In this day and age, any person will probably want to take their family sightseeing or on a vacation in their own car,” he said. “Most consider [affordable cars] normal, just a basic need, because nowadays we are all using phones and watching televisions.”

Unless the trend in car import policies is reversed, prices are likely to remain high for many years.

Myanmar has seven local and six foreign investments in SKD manufacturing, according to Myanmar Investment Commission, including Suzuki, Nissan, Kia, Ford, Lifang and Isuzu.

“There has not yet been any further proposals for SKD since the new investment law was enacted,” said U Soe Myint Aung, a director at MIC.

Used cars: stalled market

The picture is arguably bleaker for those selling used cars. This business takes place at both dealerships and among freelance brokers, many of whom take advantage of the individual “free import” system to acquire cars through agents.

U Ye Htut is the founder of the Automobile Dealing Group Social Work Association, which was set up by brokers who gather at the old Thirimingalar market, in Kyeemyindaing Township.

Many brokers are wondering whether they’ll have a job in the future, he said.

“The government should show more consideration for our business because the majority of people can only afford to buy cars from brokers,” Ye Htut said.

Since the vehicle import committee’s announcement last month, used-car prices have jumped sharply and sales have slowed.

“Our market was one of the busiest places to do business in Yangon, but since the new policies have been announced our status has gone down steadily,” said U Kyaw Moe, a broker from the Bar Tar used car market in Hlaing Township. “Our country will still need used cars in the future so I want the government to make sure there is a place for us to trade them.”

A summary of changes to the used car import policy in Myanmar. (Frontier)

Policy expert Dr Zaw Oo from the Center for Economic and Social Development said that the vehicle import committee should consider the needs of middle class households, which can only afford to pay around K10 million for a car.

While welcoming the shift to importing only left-hand-drive vehicles, he said he was concerned that the government seems opposed to affordable used-car imports.

“They didn’t clearly state whether they support importing used cars,” he said.

He noted that even some developed countries import large numbers of used cars, citing the example of New Zealand, where more than 40 percent of imports are used cars, mostly from Japan.

“If the government wishes to [restrict imports], I would like to say it will probably have to reconsider its policy,” said Zaw Oo, who was an economic adviser to Thein Sein.

A taxing issue

Zaw Oo and many others interviewed for this article also criticised the high levels of tax on both imports and locally assembled cars.

Importers pay at least five taxes, including Customs duty, commercial tax, income tax, special goods tax and a registration fee.

But Internal Revenue Department director general U Min Htut defended the tax rates, describing them as “normal”. He said they were only high if importers and buyers could not show white money – income on which they have already paid tax.

“If they can prove with evidence [they have paid tax] the purchase price will be lower,” he said. “Black money can’t be used in other countries. Instead of rejecting it completely though, we set high taxes to encourage people to follow the rules.”

The tax rates vary from 67 percent to 217 percent for imported vehicles. It’s unclear exactly how much difference the lack of white money makes, but some suggested that it means importers pay double the amount of tax they would normally.

Cars assembled locally incur only a 15 percent income tax, which can be waived if the buyer shows evidence of having paid tax, Min Htut and others in the industry said.

Some suggest the committee should introduce a more detailed policy that encourages the import of certain types of vehicles considered good for the economy.

“For light trucks and pick ups that are for business or industrial use, they should allow older models to be imported,” said U Moe Kyaw Swar, vice chair of the Myanmar Automobile Manufacturer and Distributor Association.

He also expressed concern that the decision to restrict imports will result in used cars that were imported since 2011 remaining on the country’s roads indefinitely. Many are already 15 years old and without proper maintenance could become unsafe.

“Because the policy does not allow models earlier than 2014, most people who need to buy a car will just seek out older ones that are already here,” he said.

Some are calling for the government to invest more in public transport so that those who can’t afford to buy a car at least have a comfortable alternative.

“This policy is obviously aimed at reducing the traffic congestion in Yangon and also to reduce the trade deficit,” said Ko Ayay Kyo, joint general secretary of the Myanmar Organisation for Road Safety.

“It’s impossible for everyone to own a car … If every resident of Yangon owns a car, the traffic will be so horrible,” he said. “Instead, governments have to focus more on providing good public transport.”