With the hot season well underway, residents fear worsening cuts to come, while rising fuel prices and an increased reliance on gas generators threaten to send business costs and commodity prices soaring.

By FRONTIER

When the power came back on at 1am, everyone sprung into action. In the factory workers’ hostel where Ma May Si lives, in Yangon’s industrial East Hlaing Tharyar Township, some ran to take showers while others began cooking food for the coming day. Others flocked with devices in hand to power outlets to charge dead batteries while the current still flowed.

“It doesn’t matter what time it is — we must do as much as possible when the electricity is back on,” May Si said. “If it’s 1am, we have to get up and cook and wash our clothes. The building becomes a hive of activity.”

Since February, the daily routines of most Yangonites have been thrown into disarray by irregular but constant power cuts that often last hours at a time. Lights go out, fans stop spinning, and the pumps that bring running water into homes go silent. March and April, workers say, have been even worse.

May Si’s hostel is a four-storey building with eight rooms on each floor. By the time the lorry — packed shoulder-to-shoulder with tired and sweaty factory workers — dropped her off from work at around 6:30 that night, all she wanted was to wash the day’s grime from her body. But the building was once again in darkness.

The power had been off since 1pm, her roommates told her.

The residents of each floor, mostly low-wage factory workers like her, share a bathroom with one toilet. “Sometimes, when the electricity has been cut for 10 hours or so, there isn’t even enough water to fill the toilet,” she said.

“I am so tired when I get home. All I want is a shower,” she said. “But if there’s no electricity I just have to wait.”

As April heats up, the crisis is expected to worsen.

Painful reminders

Power shortages have always been common during lower and central Myanmar’s hot, dry months of March and April, when electricity demand peaks. The outages this year, however, are said to be the worst the country has seen in over a decade.

“It reminds me of 2007 and 2008, when the electricity would be cut nearly the entire hot season,” said U Tin Win*, a retired civil servant from Mayangone Township who did not want to use his real name for fear of reprisal from the junta. “We experience rolling blackouts every year, but I have to say, this is the worst.”

For those old enough to recall it, the cuts are painful reminders of the past. Tin Win said today’s outages remind him of the long blackouts that occurred under the governance of the State Peace and Development Council, the country’s last military dictatorship.

Since they began in February, many have endured regular outages of more than 12 hours at a time. Outside Yangon, people have reported cuts that have lasted entire days.

The blackouts are also causing water supply problems, especially in urban areas where residents living on higher floors rely on pumps to bring water into their apartments.

“The electricity is usually on for only six hours a day, and when it does come back on, it often cuts out after just a few minutes, since so many people need to pump water or use their stoves. There’s a massive, immediate surge in demand, ” Tin Win said. “It’s extremely frustrating.”

The junta has blamed the blackouts on repairs being carried out at offshore natural gas projects, and on distribution disruptions caused by attacks on transmission lines — one target of the widespread armed resistance to the junta. Another reason, the junta’s Ministry of Electricity and Energy said in a March 6 statement, is that some liquefied natural gas-fired power plants have suspended operations due to high gas prices.

The political chaos wrought by the coup has sunk the value of the kyat, fueling steep rises in gas prices. The junta-controlled central bank recently banned foreign currencies and has forced companies to convert US dollars to kyat at a fixed rate of US$1 to K1,850, making importing gas, or any other commodity, less and less profitable.

On April 19, panic around a rumoured gas shortage gripped the nation, and long queues formed at gas stations even as some stations began to restrict sales. Junta spokesperson Major General Zaw Min Tun acknowledged that some companies “announced that they ran out of petrol after the new exchange scheme”, but dismissed claims of a widespread shortage.

Maximum daily output under the overthrown National League for Democracy government was about 4.2 gigawatts, which drops down to 3.1 GW during the dry season. Now, the junta says it can only generate about 2.2GW a day. It announced on March 6 that it was reducing output by 334 megawatts a day between March 12 and 18 because of maintenance work being done on the submarine pipelines that bring natural gas ashore from off the Rakhine coast. As the ministry had warned, that work caused 24-hour cuts throughout the country.

Impossible to plan

On March 18, the Yangon Electricity Supply Corporation announced a plan to provide power in the commercial capital on a four-hours-on, four-hours-off basis. At a press conference in Nay Pyi Taw on March 24, Zaw Min Tun said the scheduled outages would continue until the end of the month.

If that plan had been carried out, it would have at least enabled residents to know in advance when supply would be cut, and to plan accordingly. But residents say the cuts have been anything but predictable.

Daw Theingi Win, who owns a beauty salon in East Hlaing Tharyar, said it’s impossible to know when supply will be available.

“Yesterday, the power went off at 8am and didn’t come back on again until after 9pm,” she told Frontier on March 22. “When it comes back on, it’s often intermittent — on again, off again. There’s often no electricity during the day.”

She said the inability to plan around the cuts may soon force her to shut down her salon altogether.

Despite this, consumers are unwilling to call energy offices and complain, fearing how the authorities might respond, she said.

“Under the National League for Democracy government, people would call the township office to complain when there were outages and ask why they had occurred. But no one dares to call now, and when someone does, it’s rare that anyone answers,” Theingi Win said.

Threat of force

Long before these cuts began, residents across the country began refusing to pay their electricity bills as part of the Civil Disobedience Movement — acts of nonviolent resistance embraced throughout the country after hundreds of thousands of civil servants went on strike following the coup.

The National Unity Government, a parallel administration appointed by lawmakers in the annulled 2020 election, said in September that the tactic had cost the junta about K2 trillion in revenue in the seven months prior.

Authorities have taken to cutting off power completely for some households that refuse to pay. Increasingly, however, consumers fear soldiers may come demanding payment with guns in hand.

Soldiers began accompanying electricity office workers on home visits and guarding their offices, which increasingly became targets of bomb attacks and drive-by shootings by armed resistance forces, in the later half of 2021.

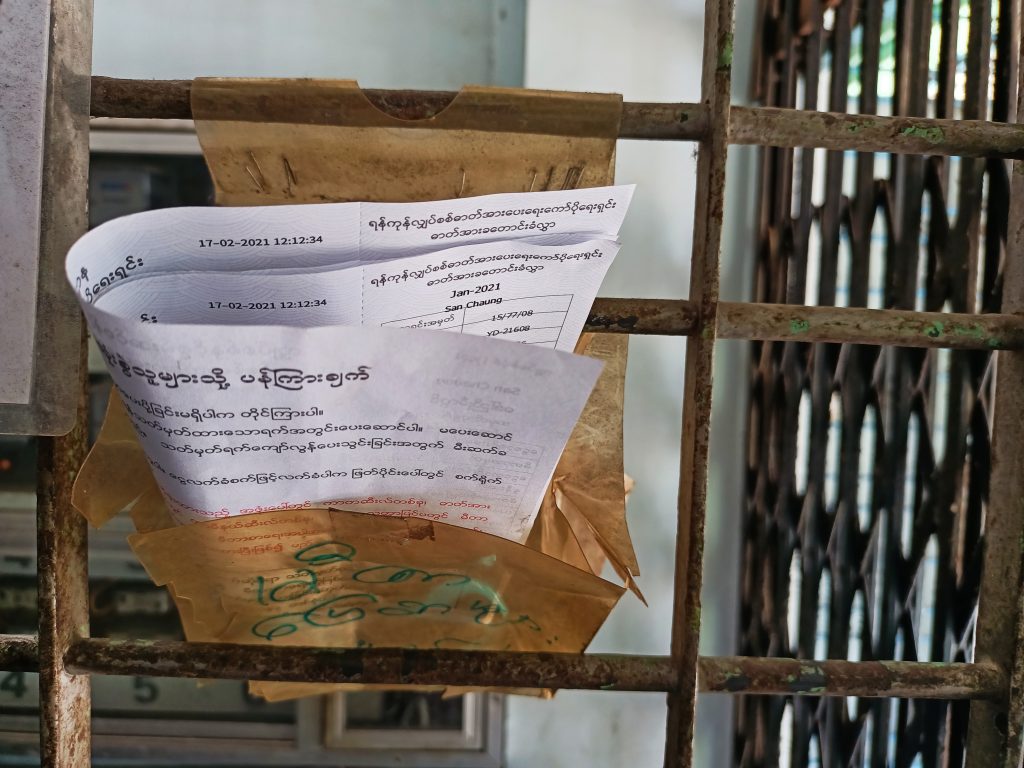

In the beginning of March, junta energy officials began sending letters demanding repayment. A resident of Yangon’s North Dagon Township, who asked that his name not be used for fear of reprisals, said his February account included outstanding amounts from last year totalling nearly K600,000. Frontier has not heard firsthand accounts of soldiers shooting or arresting anyone over unpaid bills yet, but their presence seems to be getting residents in Yangon, Ayeyarwady and Bago regions to pay up.

The same month the letters went out, a man in a rural Ayeyarwady Region village who did not want to be named told Frontier that the local energy official there threatened to call in soldiers from the nearest military base if residents did not pay. He told Frontier on March 15 that people began queuing at the office to pay their bills. He paid his bill in the first week of April.

“No one wants Tatmadaw soldiers coming into the village,” he said. “That can be very dangerous.”

Bad for business

The power cuts hurt beyond the household; they are causing economic pain as well, imposing extra costs on factories that are increasingly resorting to using generators to keep operating.

On March 18, Yangon Electricity Supply Corporation announced a daily 9am to 5pm power supply schedule for industrial zones

Meanwhile, the fuel needed to run the generators has quadrupled since the coup. Many run on diesel, which was up to nearly K2,000 a litre by mid-April, from K660 on February 1, 2021, and petrol has seen similar price spikes.

Some factories are slashing overtime hours in response. Naw Sel Sel, a garment worker in East Hlaing Tharyar, said she’s had no overtime since February.

“The factory cannot operate after 5pm, because that’s when the power is cut. The owner said he cannot afford to have workers doing overtime when there is no electricity because of the high cost of petrol to run generators,” she said.

With overtime, Sel Sel said she earned about K250,000 month. Now, she makes just K170,000 a month, including a K20,000 bonus for not taking sick leave.

“If I take just one day’s leave due to illness, I will lose K20,000 a month,” she said. “I’m afraid of taking sick leave even if I am sick.”

With the junta’s shambolic COVID-19 response, including scant testing and low vaccination rates, it’s impossible to measure the impact this may have on future waves of the virus, but it’s certain to leave workers more exposed and more vulnerable.

Still other factories may simply shut down in the coming months, depriving some of the poorest residents of all income.

Dr Soe Tun, vice chair of the Myanmar Rice Federation and the owner of rice mills in Yangon and Ayeyarwady regions, said the federation wrote to the junta’s energy ministry in early March asking for a schedule like that established in industrial zones that rice mill operators could plan around.

He said the high fuel prices have similarly hurt mill owners’ earnings.

“It costs between K80,000 and K100,000 for the petrol to run generators for one rice mill per day. I am paying nearly 3 million kyat just for petrol a month,” he said. “Some small mills have had to cease operations because they cannot cover costs.”

“It would be better if there were no cuts, but maybe the government has good reasons for cutting supply. But doing it at least according to a schedule would make it easier for us to run our businesses,” he said. Like other business owners, he was hesitant to criticise the junta.

That reluctance has angered many labour activists and organisers.

“Since the country returned to military rule, the business community is speaking with caution, which makes it difficult for those in charge to know what is really happening,” said U Ye Naing Win, secretary of the Cooperating Committee of Trade Unions.

“Businesspeople are wary about alienating the government. This is not a good sign.”

‘People must share the suffering’

Back at her workers’ hostel in East Hlaing Tharyar, May Si cooks breakfast and lunch by burning charcoal when the power doesn’t return, then eats by candlelight with her mother and son, who share her room and whom she cooks for.

She told Frontier a K1,000 piece of charcoal lasts the three of them two days.

“Even if we eat tea leaf salad as the main dish, we have to cook rice,” she said. “Prices of other basics like drinking water are also rising. Managing our budget makes me anxious.”

Of the approximately K170,000 May Si earns a month, K60,000 goes to pay for the hostel.

Soe Tun, the mill owner, said that if the manufacturers pass the rising costs of fuel and power cuts onto consumers, it will mean even higher prices across the board.

“When rice production costs go up, the price of basic commodities must go up. All consumer prices will rise,” he said.

“The people will have to share the suffering.”