The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has sent global oil prices crashing – and prompted hundreds of thousands of workers to leave a rich field of hand-dug wells in northern Magway Region.

By NAY AUNG | FRONTIER

Just a few months ago, the harsh, scrub-covered hills on the border area between Myaing and Pauk townships in Magway Region teemed with fortune seekers.

Covering about 5,000 hectares, Thabyenyo is said to be the largest hand-dug oilfield in Myanmar. Two years ago it barely existed, but today 20-metre-high triangular derricks formed from simple metal poles dot the landscape as far as can be seen, along with bamboo and tarpaulin shelters. The air is thick with the smell of oil and the sound of diesel engines.

Because the fields are unregulated – no permits are issued, and production is only taxed when it is transported ¬– nobody knows exactly how many wells there are. Sources at Thabyenyo estimate there are thousands, and that the field produces around 8,000 barrels of oil a day. If correct, this would be about two-thirds of Myanmar’s official production, which was 12,000 barrels a day in 2017.

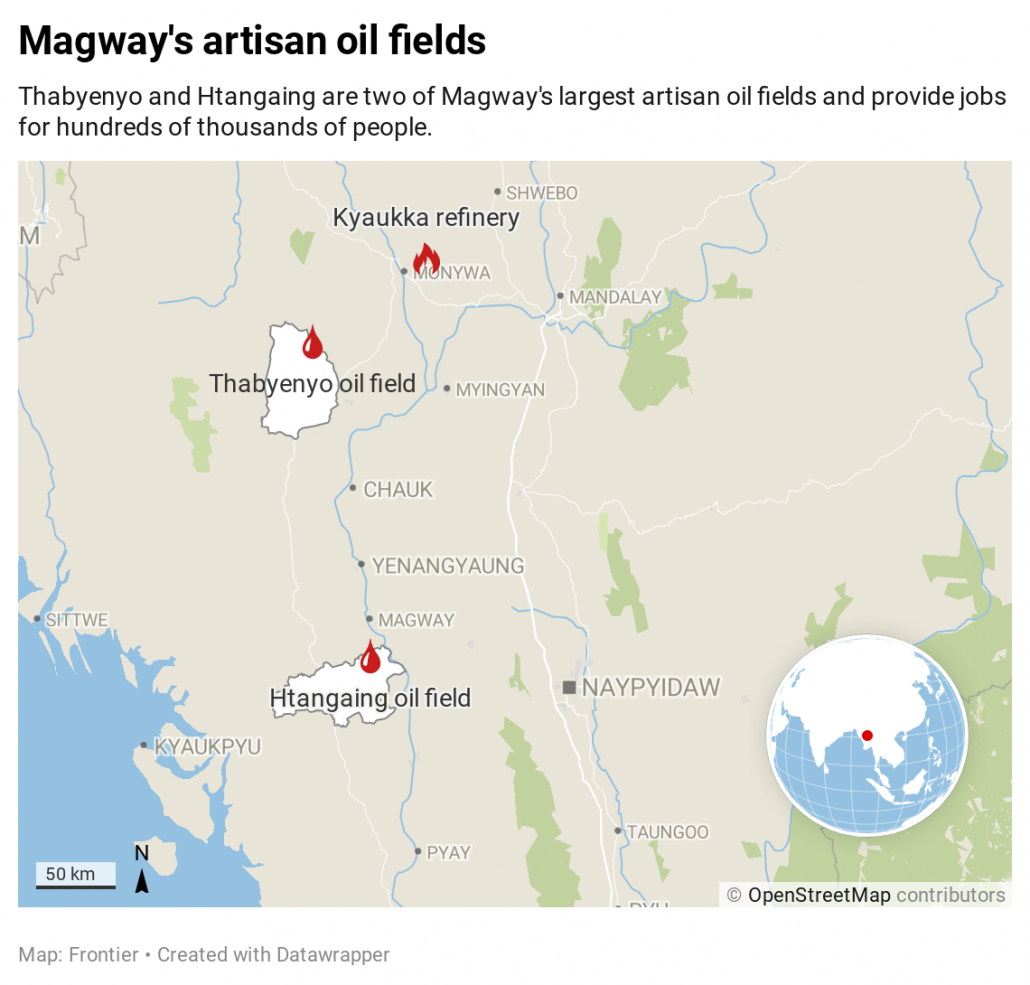

This crude is trucked to a refinery in Kyaukka, in Sagaing Region’s Monywa Township, and from there to the gold and jade mines of Sagaing Region and Kachin State.

With prices averaging K90,000 to K100,000 a barrel in 2019, it was a profitable year for many at Thabyenyo village, which is used as a base by prospectors who have come from all across the country hoping to find oil in the surrounding hills.

By some estimates, the Thabyenyo oil field on the border of Pauk and Myaing townships in Magway Region hosted hundreds of thousands before COVID-19 sent oil prices crashing. (Nay Aung | Frontier)

By some estimates, it hosted hundreds of thousands of people – labourers, investors, well owners, brokers, traders, drillers, tanker drivers and geologists, as well as those running businesses to service their needs – before COVID-19 struck, and oil prices began to crash in late February. “Prior to COVID-19, the region had around 500,000 people working in the oil business,” said local Pyithu Hluttaw representative U Ye Tun Win (National League for Democracy, Pauk).

The oil price fall sent shockwaves through the field. As prices began to plummet in February and March, well owners faced a difficult decision. They were losing money on every barrel they produced, but wells can’t be turned off like a tap ¬– if they stopped production, they’d have to invest in drilling another well when prices began to increase.

Most tried to continue producing oil and wear the losses. But by March 15, there were no buyers for oil anymore and the majority of workers had already returned home, said Ko Zayar, a 32-year-old oil trader at Thabyenyo. Production at Thabyenyo was also affected by transport restrictions imposed in response to COVID-19. When Myanmar recorded its first confirmed case on March 23, locals closed the main road from Thabyenyo to the refineries at Kyaukka.

As much as possible, operations were put on hold; owners retained a few workers to draw oil from the wells and, where possible, store it for sale later.

“Only a few workers who ladle out oil and watchmen remained. All the other businesses came to a halt,” said Zayar, who is originally from Magway’s Minhla Township, another oil-producing region about 250 kilometres south of Thabyenyo.

From March 15 it became impossible to sell oil and most people left Thabyenyo, but well owners retained a small number of workers to continue drawing oil and watch over their equipment. (Nay Aung | Frontier)

After a month-long halt, some operations resumed at Thabyenyo on May 2, Zayar said. Oil was fetching just K35,000 a barrel but soon rose to K55,000 in the second week of May and was K65,000 in mid-June.

Despite this minor recovery, the narrow dirt roads around Thabyenyo that just three or four months ago were packed with tankers, trucks and motorcycles are still mostly deserted. The many shuttered shops and silent derricks reflect that the good times are over – at least for the time being. Locals estimate that around 60 percent of people who were at Thabyenyo in February are still yet to return.

Their return is likely to depend on the direction of oil prices, Zayar said. “Unless prices recover further, I’m not sure that owners will continue to invest in production,” he said.

“If there is a further fall in the price nobody will be able to withstand it and they will return to their homes leaving only the watchmen,” he said. “I’m worried.”

Where possible well owners at Thabyenyo are storing oil for sale once prices recover. (Nay Aung | Frontier)

High investment costs

For a brief moment, the coronavirus-induced drop in demand pushed world prices below zero for the first time; as storage space ran out, producers had to pay customers to take crude off their hands.

Even if prices in Myanmar never fell that low, it’s a problem that well owners at Thabyenyo and elsewhere in Magway Region can sympathise with. Many have resorted to renting land near their wells, where they’ve created reservoirs to store oil by digging large holes with back-hoes and lining them with plastic sheeting to ensure the oil doesn’t seep into the ground. Others are paying to keep their oil in barrels.

“Storing oil in a large hole lined with a plastic sheet is cheaper than a metal storage tank. Depending on the size you can store up to 1,000 barrels,” Zayar said.

With prices so low, few wells are being sunk. An exploratory well costs at least K20 million, said U Mar, a well owner at Thabyenyo. Investors also need to pay between K2 million and K5 million for a plot big enough to sink a well and are required to give the land owner one barrel from each 20 barrels produced.

“The investment costs here are high,” U Mar said. “Out of 10 exploratory wells, about two or three will be successful. Land prices here are also high. However, investors love this area because many wells have an abundance of oil; it gushes out in some wells.”

A mobile shop at the sprawling field of Thabyenyo, which barely existed two years ago. Many shops have closed and sales are down at those that have remained open. (Nay Aung | Frontier)

U Aung Khaing Win, who sells fuel at Thabyenyo, said exploratory wells can cost up to K100 million because of the depth they need to sink them. “If you don’t strike oil after sinking three such exploratory wells, you can go bankrupt,” he said, adding that some investors form partnerships for such ventures to spread the risk.

Reflecting the downturn in business, Aung Khaing Win said his daily fuel sales had fallen from around K1 million a day to about K250,000 since the COVID-19 crisis began.

“The impact from the fall in the price of oil has been more noticeable here than anywhere else,” Aung Khaing Win said.

There’s a saying that the only way to make money in a gold rush is by selling shovels. But many of the businesses that have sprung up to support the oilfields, such as restaurants, teashops and betel stalls, are also struggling. COVID-19 restrictions have also made it more expensive to transport goods, forcing them to raise prices even as the number of customers has declined.

“Although the price of oil has fallen during the COVID-19 period, the price of thinks like food and basic commodities has risen,” said U Han Win Aung, an oil trader at Thabyenyo.

Oil wells at the Htangaing field in Magway Region’s Minhla Township. Prices at Htangaing are K50,000 a barrel ¬ about K15,000 lower than Thabyenyo ¬ and well owners say they are only able to cover labour costs. (Nay Aung | Frontier)

‘We can only cover our labour costs’

Thabyenyo is one of several small-scale oilfields in Magway Region, where hand-sunk wells have been producing oil for about a century.

The situation is no better at the other oilfields, where prices fell to just K32,000 a barrel in the first week of April.

They have since risen to about K50,000 – Thabyenyo prices are generally K15,000 higher than other fields in Magway – but business remains slow because this is not enough to cover the cost of production.

People in the industry say the situation is unprecedented.

“We couldn’t believe it at first – we’d never seen anything like it before. In the past, our problem was not being able to produce enough oil. Suddenly we had an even bigger problem – we were still producing many barrels, but we couldn’t make any money … We are making a loss on every barrel we produce,” said Ko Min Min Aung, 35, who produces about 10 barrels a day from five wells at the Htangaing field in Minhla.

class=

Min Min Aung said that before the price slump, investors didn’t worry too much if a well failed to strike oil. They’d lose their investment, but the fields were producing so much oil that they were confident the next one would hit paydirt.

“We are used to such situations; if we had some money left, we would sink another well,” he said. “But the present situation is different. If we strike oil, we are still losing.”

U Khin Maung Win, another well owner at the Htangaing field, said the cost of production had actually risen in recent months because COVID-19 restrictions had made equipment and supplies more expensive.

“The price of oil has dropped, but labour costs have not fallen,” he said. “The low [oil] price means we can only cover our labour costs – nothing else.”

Workers are paid K10,000 a day at Htangaing and other oil fields in Minhla Township. (Nay Aung | Frontier)

At fields in Minhla, workers who ladle the oil seeping from the wells into a container are paid K10,000 a day. At least two are needed in each well. Although the price has fallen, the ladling of the oil must continue if the owner wants to keep the field running in the future.

“If the oil is not removed from the well by ladling it will become too thick,” said Daw Kyawt Kyawt, a Htangaing village resident, who has her own well and has sold some of her land to other investors for drilling.

Because of the lower production, the price at Htangaing and other fields at Minhla for a plot big enough to sink a well is significantly less than at Thabyenyo, ranging from K500,000 to K2 million.

Drilling is also less expensive because the wells do not need to be as deep.

It costs about K50,000 to produce a barrel of oil at Minhla, so the current price means many producers are operating at a loss.

“If we sell now, we will lose,” said U Zaw Win, who produces oil at Htangaing and is paying traders K2,000 a barrel to store oil in warehouses because he does not have storage facilities.

An oil worker on a derrick at the Htangaing field in Minhla Township. The field hosts 20,000 to 30,000 people. (Nay Aung | Frontier)

Despite the hard times, the number of people at the Htangaing field has remained steady at about 20,000 to 30,000, several sources said.

For locals, there are few livelihood options beside oil. The wells have been dug on farmland, but once the land has been used to produce oil it becomes contaminated and can’t be cultivated again, farmers said. As a result, only a few well owners, who have access to land that was never used for oil production, are preparing to return to farming.

“I’ve been in the oil business for seven years and I’ve never seen such a situation,” said well owner Khin Maung Win. “But I’ll keep going, even if I lose money. This is my career – I have nothing else to do. And anyway, prices will go up again eventually.”