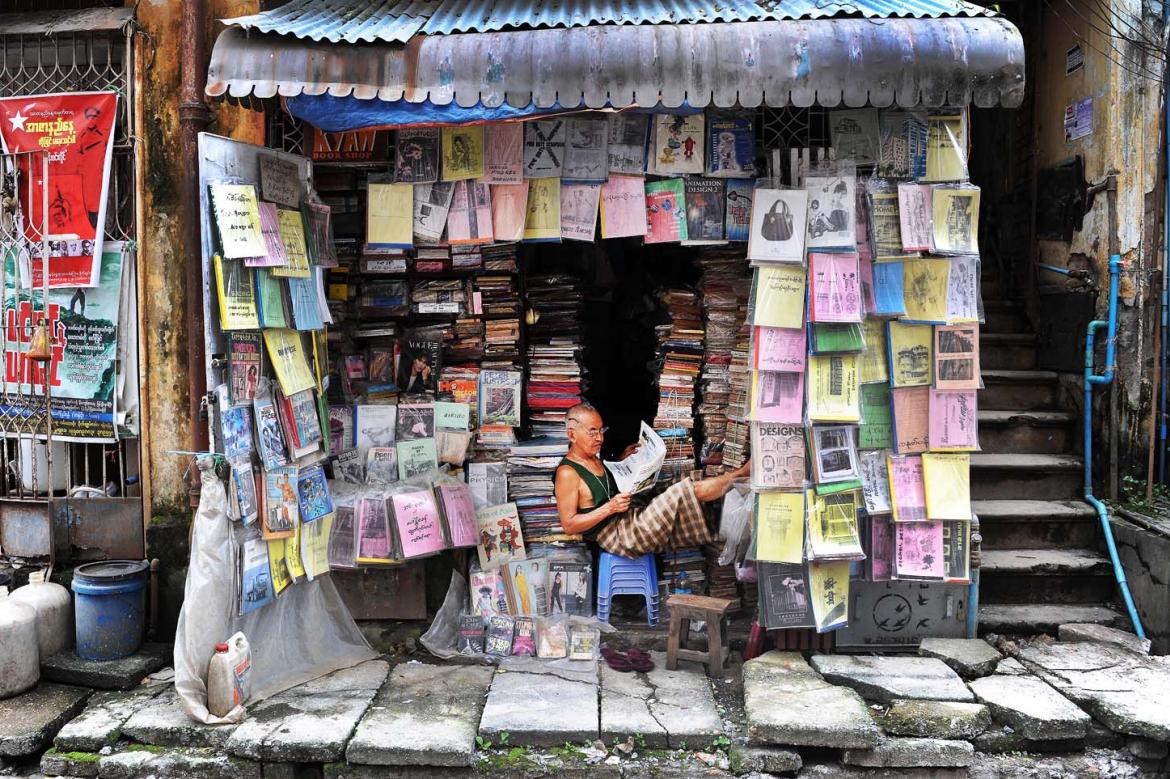

Censorship remains a challenge for moviemakers in Myanmar, but the Wathann Film Festival is able to screen uncut productions at the Goethe Institut, one of its two venues this year.

By EVA HIRSCHI | FRONTIER

AS THE LIGHTS dimmed at Waziya Cinema, the crowd settled in for the first movies of the eighth annual Wathann Film Festival, with screenings for this year’s event also held at the recently re-opened Goethe Institut.

The opening programme at the Waziya, Yangon’s last standing colonial-era cinema on Bogyoke Aung San Road, included Seasonal Rain, a short film by director Ko Aung Phyoe about a budding romance. When a scene showed the main character lying in bed and smoking a cigarette, a “smoking prohibited” sign appears in the upper right corner. A few people laughed, probably foreigners; the Myanmar in the audience were accustomed to such interventions by the Ministry of Information.

Every movie screened in public in Myanmar needs to be approved by a censorship board comprising ministry officials and members of the Myanmar Motion Picture Organization. “I wasn’t surprised by the sign; I knew about it and I’m used to it,” Aung Phyoe said.

Initially, he wanted to include a kissing scene but was certain it would not pass the censors. “Also, I was concerned about the reaction of the people as we were shooting in public,” he said.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Movie enthusiasts attending Wathann Film Festival. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

Aung Phyoe found another way to show the unshowable: As the young couple sit beside a waterway – sunset, romantic music in the background – the man grasps the woman’s chin and lifts her head, looking into her eyes. What happens next is obvious to everyone, even though it’s not shown.

Is this self-censorship?

“I’m trying not to get influenced by such things, but as a Burmese moviemaker you can’t help but think about it,” Aung Phyoe admitted. “What Myanmar needs to understand is that moviemakers don’t just want to show intimacy or nudity for the sake of it. There is always a message behind, a reason why the film director wants to include it.”

Wine, but no sip

It was not the only movie on this year’s festival programme to experience intervention by the censorship board.

In the short film Whispers of Silence, directed by Ko Zaw Bo Bo Hein, the board wanted to cut a scene in which a woman drinks wine with a man, as well as a scene in which the main protagonist throws a bottle of holy water on the floor.

“We discussed this issue and tried to convince the censorship board that it’s only a fictional character, not the actor as a person, who throws the holy water on the floor,” said festival director Ma Thu Thu Shein. A compromise was negotiated in which the holy water scene was retained and the woman was shown raising a glass of wine to her lips, but the image of her taking a sip was cut.

Zaw Bo Bo Hein says censorship does not curb his creativity.

“I don’t care about the censorship; I’m an independent filmmaker and I shoot what I want,” he said. “If they have a problem with it, I’m simply not going to show my movie in the cinemas but look for another venue like a gallery instead.”

Moviemaker Ko Zaw Bo Bo Hein and festival director Ma Thu Thu Shein. (Eva Hirschi | Frontier)

The movie screened uncut at the Goethe Institut, a non-profit German association that promotes the German language and international cultural exchange, which was the other venue of this year’s Wathann Film Festival.

“This is the reason why we showcase the movies at both venues,” said Thu Thu Shein. The Goethe Institut, which re-opened earlier this year on Kaba Aye Pagoda Road, supports the festival by sponsoring the prizes for its Myanmar short film competition.

Political topics

In a departure from previous festivals, no political scenes were banned this year by the censorship board.

“Political topics are not as much a problem as long as they talk about the past,” said Ko Thaiddhi, the festival’s programme director. There is also another reason. Since the National League for Democracy government took office in 2016, no movies critical of the contemporary political situation have been submitted for screening at the festival.

“Maybe one reason is that we focus more on creative and artistic movies; the Human Rights Human Dignity International Film Festival is the place for political movies,” said Thaiddhi.

However, the founder of the Human Rights Human Dignity International Film Festival, U Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, said it would not be held this year or next because of his professional commitments.

This was one of the reasons why the Wathann Film Festival introduced “The Reflection of Society”, a new category for entries.

“We want to give a platform to social-political movies as well, as we think it’s important to show them,” said Thaiddhi. There were four movies directed by women in the category and they focused on landmine victims, a slum inhabited by Cyclone Nargis survivors, a woman revolutionary with a handicapped daughter and a Myanmar village affected by religious conflict.

Thaiddhi said it was difficult to know how the censorship board would react to a critical movie about politics.

“The criteria are always changing; sometimes they ban cultural things, sometimes political, you never know,” he said. A scene banned one year had been allowed the next.

“The problem is that the criteria are not well defined. For example, one point [in the censorship guidelines] states that the movie should not disrespect any religion. In principle, I agree on that; but the problem is that it’s not clear what this means exactly.”

Panel discussion with Fransiska Prihadi, Thaiddhi, Lim Han Loong and Sanchai Chotirosseranee. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

A new Motion Picture Law has been drafted and is being passed between the MMPO and the Ministry of Information, before it is sent to parliament.

Thaiddhi said he hoped the law would introduce a system to rate movies according to their suitability for young and adult audiences, a move that Aung Phyoe agreed would be a step forward.

The overseas option

Another solution for Myanmar’s moviemakers is to showcase their movies abroad, which would allow them to circumvent censorship as well as gaining international recognition and, hopefully, funding.

“There is still a lot of potential for Myanmar’s film industry, so we decided to focus more on education,” said Thaiddhi. “We organised panel discussions and a master class to encourage young directors to make feature movies, not only short movies,” he said.

A master class by Thai producer and international film festival programmer Mr Raymond Phathanavirangoon explored the “ideal pathway” for short filmmakers to make their first feature film, and included how to raise funding overseas.

Another master class held by Hong Kong-born film editor Ms Mary Stephen focused on how to enhance storytelling by editing. There were also two panel discussions with international participants that discussed audiovisual preservation in Southeast Asia as well as short film festivals in the region.

The focus on Southeast Asia was deliberate. The festival’s S-Express category featured short films from Myanmar, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

Thaiddhi said the festival wanted to provide an insight into the development of film-making in Southeast Asia and to show “Burmese filmmakers and audiences that good quality movies do not only come from Paris and New York and that our region makes high-quality productions”.