Yangon’s Drug Elimination Museum is cavernous, crumbling and weird, but not that weird.

By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER

If you haven’t heard of it, the Drug Enforcement Department’s towering gallery in Kamaryut Township has been described by publications such as Vice and The Atlantic (and all of my expat friends who have visited) as a surreal house of horrors packed with dioramas of skeletal drug addicts, organs and fetuses in jars and glittering shrines to Tatmadaw heroes.

Its reputation preceded it right up to the huge building’s entrance, where I met two American guys on their way out.

“Get ready, dude,” one said. “It’s f***ing hilarious.”

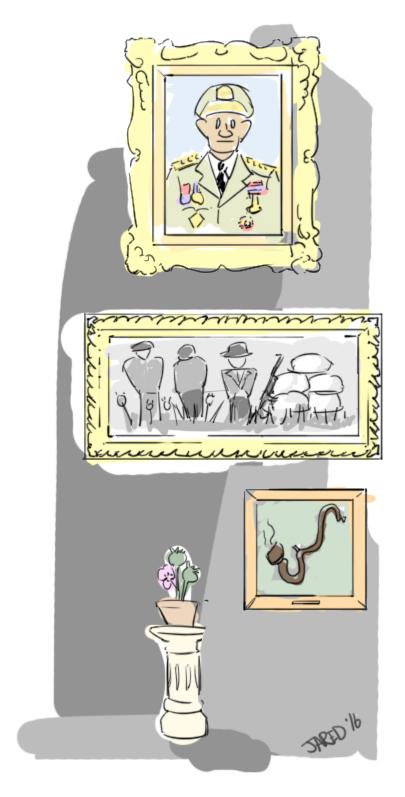

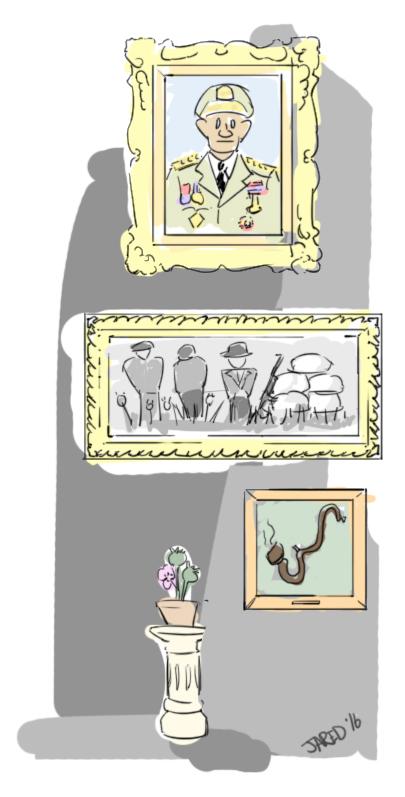

Inside the building at the corner of Hanthawady and Kyun Taw roads, a huge portrait of former Senior General Than Shwe welcomed me into a cavernous space, but the only really bizarre part was how empty it was. I was apparently rather lucky to meet the Americans because I didn’t see another soul save for a handful for cleaning staff (who were sleeping) and the curator.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Jared Downing / Frontier

A thin, middle-aged man with spectacles, the curator has run the museum for the DED since it opened in 2001. He gave me a personal tour of the first floor displays. Yes, some were pretty whacky. There was a ten-foot stalk of real cannabis, blood-spattered puppets of British redcoats and Chinese coolies bayonetting one another, and a house-of-horror-style walkthrough, with melancholy violin music, showing a druggie’s odyssey from rock-n-roll concerts to vulture-pecked corpse in the gutter.

But I grew up watching similar “this is your brain on drugs!” scare tactics, and anyway, Myanmar has a tradition of colourful narrative tableaus. For the most part, the museum featured, well, normal museum stuff: old newspapers, photos, and books; poppy plant diagrams and narcotic-producing machines; maps and detailed records of former Snr Gen Than Shwe’s drug war campaigns. One hand-painted mural illustrating opium crop substitution was so pretty I wondered where I could get a print.

There were, of course, heaped spoonfuls of propaganda. But even the propaganda was skilful, from a narrative point of view, casting poppy as an age-old common enemy under which even the rebel factions involved in its production are victims. And anyway, you could find worse vehicles for your agenda than “drugs are bad”.

“This used to be a lot more impressive,” the curator sighed at a life-sized model of a jungle lab for converting opium to heroin. It once had a working river and waterfall, nature sound effects and outdoor style lighting, although they haven’t been activated in years.

He began to speak with pride about how historians, public archivists, military officers, designers and artists all came together to bring life to the museum 15 years ago. But the junta began to lose interest when it moved the capital to Nay Pyi Taw and Snr Gen Than Shwe yielded power. Today the museum is entirely self-funded, but its most common visitors, groups of school kids on excursions, pay nothing. The museum’s skeleton staff do their best to maintain the place, but displays sit dim and gloomy for bored expats to mock.

The curator is fearful that the government will sell the land to a private developer. He was so candid I felt compelled to tell him I was a journalist. “You can write about our museum in your magazine!” he said. “You can tell other foreigners about us!”

Oh, foreigners already love you, I thought, dolefully. They think you’re “f***ing hilarious.”

I didn’t tell the curator that some foreigners like his museum specifically because he can’t keep the lights on. That some only come to laugh at the big, military-funded building left to crumble and the extravagant fountains left dry. To chuckle at how disappointed some official must be that his vast hallways aren’t packed with happy tourists.

And you and your staff, I didn’t tell him, are just part of the joke. So don’t worry. The harder you try, the more fun they have.