The most recent attacks on security forces in the region came just hours after the commission led by Kofi Annan submitted its final report to the government.

By MRATT KYAW THU & OLIVER SLOW | FRONTIER

DEVELOPMENTS IN northern Rakhine State took a sinister new turn last week, when coordinated attacks were launched on police outposts, leaving at least 100 dead and thousands more displaced.

The attacks were conducted by the Arakan Rohingya Solidarity Army, the same group that launched offensives in October last year, that led to “clearance operations” by security forces and dramatically altered the dynamics in the already troubled region. The operation brought accusations of human rights abuses that the government and military have vehemently denied.

The government has officially declared ARSA a “terrorist group”.

The latest violence began late on the night of August 24, just hours after the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State submitted its final report proposing long-term solutions for Rakhine State, which has been affected by sporadic bouts of violence since 2012 and where about 120,000 people – mainly Muslims who identify as Rohingya – remain displaced.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Border Guard Police officers stand guard at a village in Buthdaung Township. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

The violence has left more than 100 dead since Friday. Ethnic Rakhine and other residents of Maungdaw have been evacuated to Rathedaung and Sittwe, the state capital, while thousands of Rohingya have fled to the border with Bangladesh.

But authorities there have refused to let most of them cross, with reports saying that thousands of people, mainly women and children, are stranded near the border.

Immediately after the attacks, an unverified Twitter account purporting to represent ARSA claimed responsibility for the attacks, saying they were a “legitimate step” to “liberate” the Rohingya.

On August 26, an AFP reporter and a Bangladeshi soldier at the Ghumdum border post said more than a dozen mortar shells and countless machine gun rounds had been fired by security forces towards Rohingya trying to flee across the border into Bangladesh. It was not immediately clear if any were hit.

About 20 staff based in northern Rakhine for international agencies left Buthidaung port for Sittwe on the afternoon of August 27. Meanwhile, about 200 civilians have been displaced by the violence around Maungdaw and Buthidaung.

On August 8, state-run newspaper Global New Light of Myanmar carried a statement issued by the State Counsellor’s Office issuing a “warning”, where it accused staff from international agencies of having colluded with ARSA.

It also said that any “writing in medias in support of extremist terrorists and ARSA are banned and if those acts described above are found committed in domestic, action will be taken in accordance with Counter-Terrorism Law”.

‘Under control’

Speaking to reporters in Sittwe, the state capital, on August 27, Rakhine State chief minister U Nyi Pu said the security situation was “under control”, having visited the affected area earlier that day.

“We arrived in Buthidaung and Maungdaw. We went to downtown Maungdaw and studied the situation. To tell you about the security, it seems to be under control,” Nyi Pu said. The chief minister had visited the affected area alongside Dr Win Myat Aye, the Union Minister for Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement.

However, the chief minister had not been able to visit the whole of the affected area.

“To tell the truth, I haven’t seen the whole of Maungdaw District, but according to Tatmadaw, Border Guard Police and administrative officials, we can say that according to the security measures, the situation is under control,” Nyi Pu said.

Win Myat Aye arrived in Sittwe on Sunday, where he met with state government officials before travelling to Maungdaw and Buthidaung by helicopter. He returned to Sittwe the same evening.

He said they had seen several holes that appeared to be caused by bombs along the roads around Maungdaw.

“The soldiers and security forces were not able to go as far as they thought they could,” Nyi Pu said. “They had to clear the mines, and bridges were destroyed. Because they had to walk, there were many delays.”

‘A new crisis’

On August 27, Brussels-based think-tank International Crisis Group published a report whereby it said that the current crisis engulfing northern Rakhine State was “neither unpredicted or unpreventable”.

It said that the emergence of ARSA last year was a clear signal that the situation in Rakhine State needed not only a “security response”, but also political action.

“The Myanmar government has not moved quickly or decisively enough to remedy the deep, years-long policy failures that are leading some Muslims in Rakhine State to take up violence,” the report said.

It pointed towards the “extreme discrimination” towards the group, as well as the erosion of rights in relation to obtaining citizenship documents and the disenfranchisement of the Rohingya before the 2015 general election.

“These factors, in combination with the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Rohingya communities that resulted from separate violence in 2012, and the military crackdown last year that targeted civilians, create an environment where ARSA can increase its legitimacy and recruiting base among local communities and more easily intimidate and kill Rohingya who disagree with it and lack any real protection from the state.”

Rohingya residents inside a village in northern Rakhine State. (Oliver Slow | Frontier)

The attacks will also harm the group’s claim that it is fighting for the cause of the Rohingya, it said, adding that the group will face “international censure” for the attacks.

It said that the ARSA are likely aware that their attacks will lead to a strong military response, as they did in the aftermath of the 2016, and harm Rohingya villagers, many who have already been forced to flee.

“Despite its claim that it is ‘protecting’ the Rohingya, it knows that it is provoking the security forces into a heavy-handed military response, hoping that this will further alienate Rohingya communities, drive support for ARSA, and the place the spotlight of the world back on military abuses in northern Rakhine State.”

At the same time, a heavy-handed security response would also work against the interests of the Myanmar government. It noted that a harsh military response and continued displacement of thousands of Rohingya would “create conditions ripe for exploitation by transnational jihadists”.

Annan Commission report

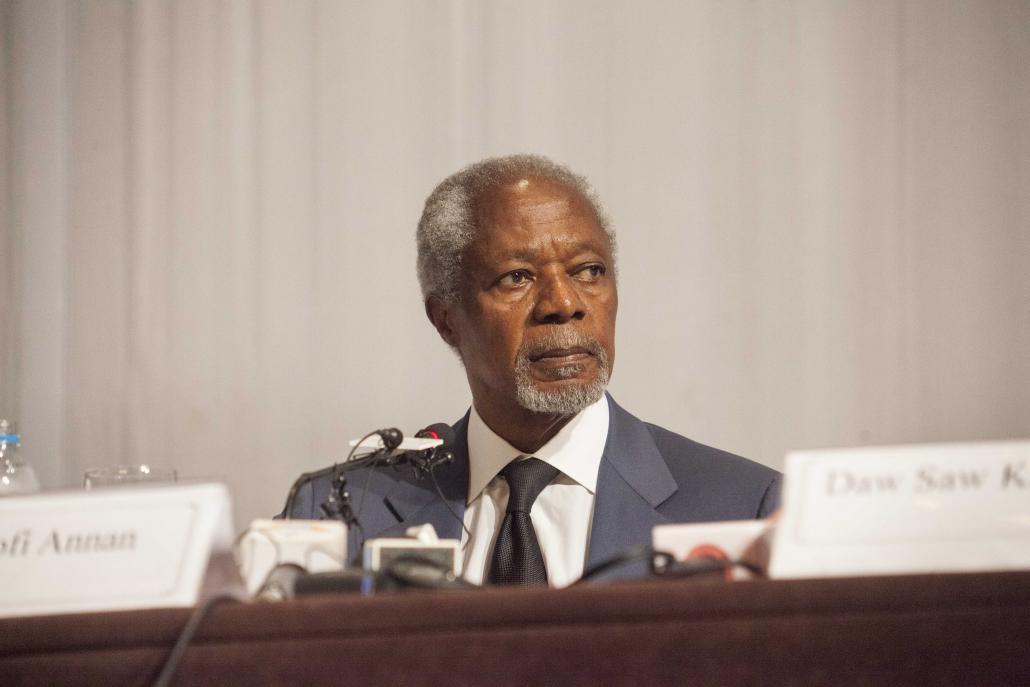

The attacks came just hours after the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, chaired by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, submitted its final report to the Myanmar government, where it called for freedom of movement for all people in Rakhine, and a review of the controversial 1982 Citizenship Law.

“The establishment of the Advisory Commission … was a frank recognition that the situation in Rakhine has become untenable, and that fresh ideas and new approaches are urgently needed to end the recurring cycles of violence, poverty and radicalisation,” Annan said at a Yangon press conference on August 24.

The report called on the government to bring the citizenship law into line with international standards and to abolish “different distinctions between different types of citizens”. The law currently recognises full citizens, associate citizens and naturalised citizens.

It also urged the government to begin a process to review the law “to ensure the equitable treatment of all citizens”.

“We are well aware that our recommendations on citizenship and freedom of movement touch on profound concerns of the Rakhine population,” Annan said at the press conference. “Nevertheless, the commission has chosen to squarely face these sensitive issues because we believe that if they are left to fester, the future of Rakhine State – and indeed Myanmar as a whole – will be irretrievably jeopardised.”

Kofi Annan, head of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, at the press conference to submit its final report in Yangon on August 24. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

While the report’s recommendations were largely welcomed by the international community, the domestic reaction was mixed.

A post on the Facebook page of Commander-in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing said “some factual flaws and deficiencies are found in the report”. The post said that “all Bengalis in Rakhine State” – using a term rejected by much of the Rohingya population – must register with the government’s National Verification Certificate process in order to gain citizenship.

Many Muslims across the state distrust the NVC process, as they believe it will make it even harder for them to gain access to citizenship.

The commission report also called for the government to provide “full and regular access for domestic and international media to all areas affected by recent violence – as well as all other areas of the state”.

In his Facebook post, Min Aung Hlaing said media teams had been allowed to pay visits to the affected area, and that the media should express the “true information”. The government has so far organised three media tours to northern Rakhine State since last October, but these have been heavily controlled by the government and security personnel.

Annan presented the report to President U Htin Kyaw in Nay Pyi Taw on August 23. A day later, the state-run Global New Light of Myanmar quoted Htin Kyaw as saying he hoped the international community would “understand the challenges and situation being faced by the government” in dealing with the Rakhine issue.

Human rights groups called on the government to abide by its findings. In a statement, Mr Phil Robertson, deputy Asian director for Human Rights Watch, praised the commission’s “straightforward approach to the thorny issues of statelessness, ethnicity and vulnerability to rights abuses.”

“The Myanmar government has promised to faithfully implement the recommendations of the Commission and this will be the key test of that commitment,” he said.

On the morning after the attacks, Annan released a statement saying he was “gravely concerned by, and strongly condemn” the violence.

“I strongly urge all communities and groups to reject violence. After years of insecurity and instability, it should be clear that violence is not the solution to the challenges facing Rakhine State.”