OPINION

A Frontier editor reflects on the legacy of the recently deceased former New Mexico governor and fringe diplomat who helped free him from prison in Myanmar.

By DANNY FENSTER | FRONTIER

I couldn’t immediately place the name. Another of the inmates at Yangon’s Insein Prison was waving a newspaper at me, telling me my governor had arrived.

“It is good news,” he said. “Your governor has come and he has met with Min Aung Hlaing. This means you will be freed.”

My governor? I thought.

“Who is my governor?” I asked.

“Bill Richardson.”

Bill Richardson? I searched my mind.

“Who the fuck is Bill Richardson?”

I snatched the paper from him. Squinting under the harsh sun of the prison yard, I began to read: Chairman of the State Administration blah blah blah Min Aung Hlaing met with Mr Bill Richardson, “former governor of New Mexico State of the United States of America…”

New Mexico, I thought. Right… As a native of Detroit, Michigan – thousands of miles from New Mexico – I had forgotten the name. But I suddenly remembered he’d once run for the democratic nomination for US president.

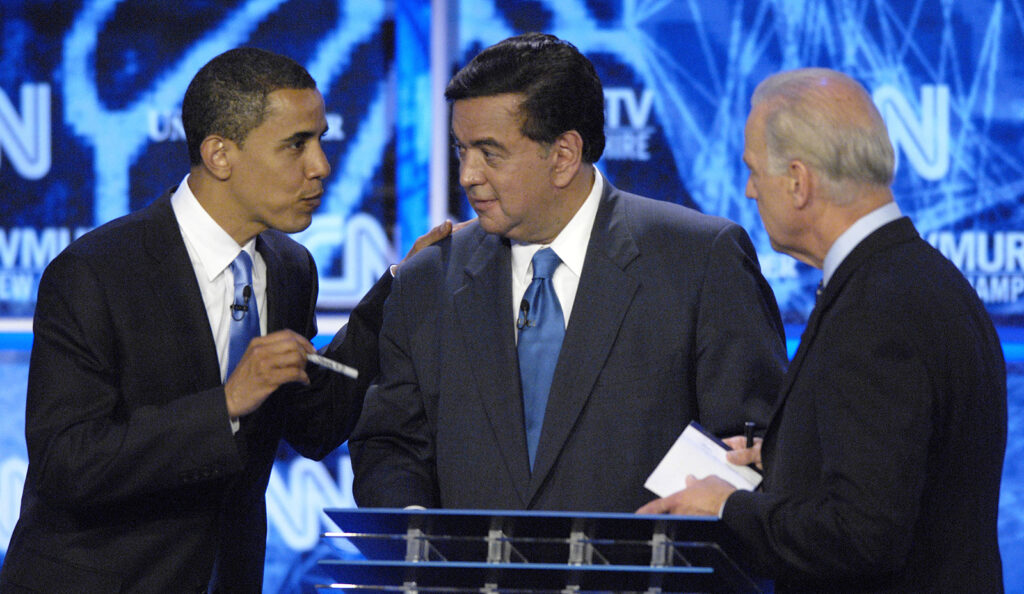

Similar thoughts likely ran through the minds of many Americans who read of Richardson’s unexpected death on the weekend. Prior to a popular governorship in New Mexico, he served in congress for more than a decade and as ambassador to the United Nations under President Bill Clinton. In 2008 he led a brief campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination before bowing out and supporting the eventual candidate, Barack Obama.

Though I hadn’t known it then, Richardson had been visiting political prisoners in Myanmar, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, since the 1990s. His foundation, the Richardson Center for Global Engagement, trained political parties ahead of elections in 2015 and 2020. In 2018, Aung San Suu Kyi appointed him to a commission charged with advising her government on the Rohingya crisis. He resigned early on, after a reportedly explosive argument with her about the imprisonment of two Reuters journalists whose “crime” was to expose a massacre of 10 Rohingya men. He saw what has since become clearer to all – that Aung San Suu Kyi’s position on the Rohingya was in basic alignment with the military’s.

What I really wish I’d known then – and what he’ll likely be most remembered for – is the career he’d made of negotiating the release of Americans held hostage or wrongfully detained abroad, including in Russia, North Korea and Cuba.

By the time Richardson arrived in Nay Pyi Taw, I had been in Insein Prison for five months. I was arrested at Yangon International Airport on May 24, 2021, while managing editor of this magazine, and charged with publishing information that might hurt the military, among other alleged crimes.

Occasionally, over five long months, I would be marched to the prison’s entrance, shackled in rusting iron cuffs and chained from ankle to wrist, then handed over to a police officer, who would slow-walk me to the mouldering shell of a building at the prison entrance where my trial was held. The court was supposed to meet once every two weeks. More often, though, a judge or lawyer would get sick or, on one occasion, break a bone, and so the trial would stop. More often still, the courts would close indefinitely, waiting for some wave of COVID-19 to pass. When the trial did occur, witnesses would fail to show, and so again things would remain at a standstill.

I met detainees from West Africa who’d been on trial for immigration violations for nearly two years and, with no embassy or consular officials in the country, had no end in sight. When Richardson arrived, I was beginning to believe I may never leave. The report in the Global New Light of Myanmar – one of the two or three state newspapers we were given day-old copies of each afternoon – said Richardson was there to discuss humanitarian pandemic relief.

“This doesn’t say anything about me,” I said to the other inmate, a middle-aged Rohingya man convicted of terrorism-related charges under circumstances that were never entirely clear to me. “This says he just came to talk about COVID relief.”

By far the longest serving prisoner in our ward, he acted as something like a prison sage. Read between the lines, he said; look for what it doesn’t say, not what it does say. Of course they spoke about me – a former US governor had not come to Myanmar and not spoken about an American prisoner.

But he had made similar predictions in the past. The other inmates had, too. Each of the 176 days I was there, everyone was certain of my imminent release except me. By then I had stopped trying to read tea leaves, or to take anything at all – the reopening of the courts, new criminal charges lodged against me – as signs of anything, good or bad. Everything was arbitrary and random. I shrugged the story off.

And then my trial moved into warp speed. Suddenly, on multiple days in a single week, I was shackled at the prison gate and handed to the police, then slow-walked to the decrepit court house, where witnesses were unexpectedly showing up.

The following week, it was every day – marathon sessions lasting from morning to afternoon and sometimes into the evening.

On Friday, my trial ended – in a conviction and an 11-year sentence. I spent the weekend desolate and confused.

On Monday, I was reclining in a private jet on the tarmac of the Nay Pyi Taw airport, clinking a flute of champagne against Bill’s gigantic glass of wine.

I didn’t get to know Bill intimately, but over the course of two flights and a layover in Doha, he was good natured and quick to laugh at himself. His hearing was going, for which we – two Richardson Center staffers on the flight and I – continually ribbed him about.

“How is the shrimp, Bill?”

“The what?”

“The shrimp, Bill! Turn up your hearing aid!”

“My what?”

He laughed this off easily, poking fun at his own aging body.

As the first jet cleared Myanmar air space, I asked him what it felt like to lock eyes with someone like Min Aung Hlaing, whose seizure of power in February 2021 was responsible for so much evil. Bill brushed such questions aside. It was the least important thing to think about, he said, when an innocent person’s life and freedom were on the line. He quickly turned the conversation back to me, asking how I was feeling, if I was sure I was okay. Like my own Jewish grandma, he told me to eat more. Then – also like my grandmother – he nodded off on the jet’s sofa.

It was November 15, 2021: Bill’s 74th birthday.

*

A great many things, large and small, led to that Monday on the Nay Pyi Taw tarmac. Governments – the US and others – pushed and nudged where they could. Private individuals worked their sources, trying to get close to anyone in Min Aung Hlaing’s inner circle. But in military dictatorships like his, final decisions are always made by just one person. There is no one else to persuade.

In the space between Richardson’s first visit and my release, a chorus of criticism rang out on social media and in the press. By meeting with Min Aung Hlaing, Richardson had offered “legitimacy” to the junta and delivered them a “propaganda win” in the form of the photograph splashed across the front page of the Global New Light – as if a photograph in that newspaper might sway anybody not already imprisoned in the cult of the Tatmadaw. As if the wanton bombing of schools and monasteries, or the systematic rape of women and girls, could ever be lent an “air of legitimacy”. Others have criticised Richardson for seemingly “reveling” in this role – and in the spotlight it brought. But fewer have appreciated his willingness to withstand such attacks, or his ability to silence the impulse toward easy moralising in pursuit of genuine results.

These qualities are only growing in importance; the use of “hostage diplomacy” has exploded in the last decade, with dictatorial regimes now holding more foreign captives than non-state militias and terrorist groups. As world leaders march us inexorably into a new cold war in which diplomatic channels are increasingly frayed, we are going to need more Bill Richardsons.

But by engagement, Richardson meant more than dealing with dictators. The center’s earlier work in Myanmar was an example of the “citizen diplomacy” that – alongside cultural, business, and academic exchanges – he hoped would promote more bottom-up and enduring forms of change. If new iron curtains do come down, it will be up to us – journalists, artists, activists – to keep the lines of communication open across cultures.

I returned to Southeast Asia just days before Richardson’s passing. I’ve come to rejoin this newsroom full-time, for the first time since my arrest in 2021. I was out with friends when the news broke – Saturday evening, Bangkok time. I don’t believe in the afterlife, yet I couldn’t help feeling Bill was smiling down on me from somewhere, watching me clinking glasses again with old colleagues and others I knew from Myanmar, each of us trying to make the best of an awful situation, and keeping those lines of communication open. I raised a glass to him.