Military-linked social media accounts, mainly on Telegram, continue to dox activists and encourage violence, including assassinations. Although two of the most controversial accounts were recently removed from the platform, critics say Telegram is still not doing enough to regulate content.

By ANDREW NACHEMSON and FRONTIER

As more police and soldiers defect from the junta, pro-military social media users are fighting back with a campaign to have security force members critical of the military arrested and to discredit those who join the resistance.

Much of this campaign against these defectors is taking place on messaging app Telegram. Despite finally banning two of the most problematic accounts this past weekend, a number of activists say the company is still not doing enough to control dangerous content, even in cases where it puts lives at risk.

Frontier previously reported that pro-military personalities were using the app to target business owners participating in a strike to mark the one-year anniversary of the coup on February 1. Some of those who were targeted in Telegram posts were arrested and had their properties seized by security forces. Now these same users are turning their attention to security forces they deem disloyal.

As of December, a group encouraging defections said 2,000 soldiers and 6,000 police officers have left the regime, although not all have gone on to join resistance groups. Most who desert claim there are many others in the ranks sympathetic to the pro-democracy movement.

Captain Kaung Thu Win, who served as a camp commander in Sagaing Region’s Monywa Township, told Frontier he decided to defect after hearing stories of the military burning and looting villages in neighbouring Magway Region. But he had a problem: his wife was pregnant.

He waited for five months – until his wife and their newborn were well enough to travel – before they fled. They spent days travelling from Monywa to Kalay, passing through security checkpoints while hiding the ammunition he had brought with him. Eventually, he met up with “revolutionaries” who took him to “liberated territory”.

“Anyone who is aware of the military’s acts of terrorism will join CDM,” he said, referring to the mass strike of civil servants known as the Civil Disobedience Movement.

On December 5, a Facebook account that apparently belonged to Police Lieutenant Colonel Zaw Win Ko condemned an attack on peaceful protesters that involved a military vehicle ramming into the demonstration and killing five people. The post compared the soldiers to “savage animals”. The lieutenant colonel was then reportedly arrested on February 8.

Kaung Thu Win warned other soldiers and police not to speak out until after they reach a safe area.

“If you are still working under the military council, you should not express your feelings… For now, be patient and keep your emotions in check,” he advised.

Less than a week after Zaw Win Ko’s arrest, infamous Telegram account Han Nyein Oo began taking credit for it.

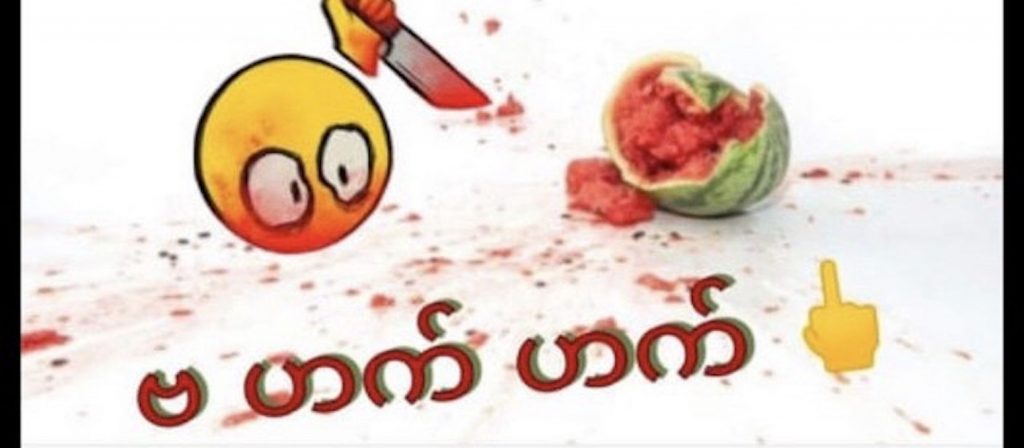

“He was invited to Insein Prison for dinner. He also lost his pension and was imprisoned,” Han Nyein Oo wrote to his 100,000 subscribers on February 14. “If you have any remaining watermelons, please bring more to @Hannyeinoo969.”

The username appears to contain a reference to the 969 Movement, an anti-Muslim Buddhist extremist movement associated with ultranationalist monk U Wirathu.

The term “watermelon” refers to members of the security forces who are “green” on the outside and “red” on the inside. The colour green is typically associated with the military, while red represents the National League for Democracy, which the military overthrew in a coup in February last year.

Han Nyein Oo’s account became inaccessible late on Friday March 11, with a notice saying it

“can’t be displayed because it violated Telegram’s Terms of Service”. But secondary accounts remain active and are growing fast. Another Han Nyein Oo channel had around 37,000 subscribers at the time the main account was blocked but has since grown to over 48,000. A new channel that was created after the block quickly garnered 26,000 subscribers.

Daw Wai Phyo Myint, a digital rights activist with Access Now, said she was “glad to see” the main account taken down, but added that it was “too late and too little” given activists had been begging for action for months. “Taking down just one account is not necessarily addressing the issues of Telegram we have been raising,” she said.

Many other problematic accounts remain active.

One called Hpayethi Hnein Hnin Yay or “watermelon suppression” in Burmese, posts screenshots of Facebook posts by soldiers and police criticising the military, demanding that action be taken against them. Another account, the name of which Frontier is withholding to limit its reach, has launched a bounty system offering payment for assassinations. In one post, the account offered K500,000 (around US$280) to anybody who kills a social media user that accuses someone of being dalan, a term for a military informant. If a target claims to have actually killed a dalan, the bounty goes up to K700,000 (around $390). The post also promised payment if the target is seriously injured. Frontier has not confirmed any actual assassinations related to this campaign. Both channels remained accessible as of publication.

In another incident, a Facebook user identified a writer and activist from a military family as a “watermelon”. The post accused the writer of starting a recent campaign to assassinate air force officers, an effort by resistance groups to limit the junta’s ability to conduct air strikes, which give the military a major advantage over resistance groups and have also resulted in widespread civilian casualties. The post shared the writer’s address in Yangon and the name of the town where he is supposedly hiding in Thailand. Although the post was taken down from Facebook, it was shared by a number of pro-military Telegram users where it remains accessible.

Not enough moderation

Despite the fact that Telegram users are seemingly inciting violence, directing arrests and encouraging assassinations, Telegram has taken only limited action. The company did not respond to multiple requests for comment from Frontier, including for this story.

Digital activists have also attempted to contact Telegram, warning in a letter that its platform was being used to “cause profound harm” with “very real consequences”.

“They don’t respond to any of our communications,” said Wai Phyo Myint with Access Now, one of the groups that wrote the letter to Telegram.

“They need to have channels where they engage with civil society and activists and journalists,” said her colleague, Ms Dhevy Sivaprakasam. Sivaprakasam pointed out that Facebook made similar mistakes, but after being implicated in the violent crackdown against the Rohingya in 2017, has been much more proactive in addressing dangerous content.

Wai Phyo Myint said it has been more of “a challenge to find a pressure point” on Telegram, given it is based in Dubai, unlike Facebook, which is headquartered in the United States.

“Telegram channels targeting pro-democracy supporters clearly intend to incite violence and should be removed for violating the platform’s terms of service,” said a Western diplomat based in Yangon who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Telegram was founded in 2013 by brothers Pavel and Nikolai Durov, who left Russia country in 2014 citing government pressure. Telegram has long resisted moderating content on its platform due to free speech concerns. But there are signs the company is starting to cave to pressure.

In February, Telegram took down 64 channels in Germany accused of spreading anti-Semitism and COVID-19 disinformation, after the government threatened to ban the platform. Telegram also banned Russian state media accounts following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Now, it has seemingly begun to respond to pressure in Myanmar as well.

Telegram also appears to have different policies for products using different operating systems, likely due to the policies of these companies. A Frontier reporter with an iPhone was unable to access one Han Nyein Oo page which had spread revenge porn targeting female pro-democracy activists. A notice says the channel “can’t be displayed” because it “spread pornographic content”, something Apple has long worked to keep out of its App Store. But a reporter with another brand of smartphone could still see it. Apple did not respond to a request for comment.

“We had discussions on whether we should approach Google or Apple to request whether to remove Telegram from their app stores, but at the end, what we want is to still have Telegram as a platform because the movement is relying on it as well,” said Wai Phyo Myint.

Telegram is also used by journalists and activists to communicate more securely. “We only want Telegram to address these problematic contents and ban bad actors,” she said.

Sivaprakasam said they also have to be careful not to inadvertently get anti-military People’s Defence Forces and other resistance groups banned. While most in Myanmar see these groups as acting in self-defence, a blanket ban on violence could impact them as well.

“This is something we foresee as an issue,” she said.

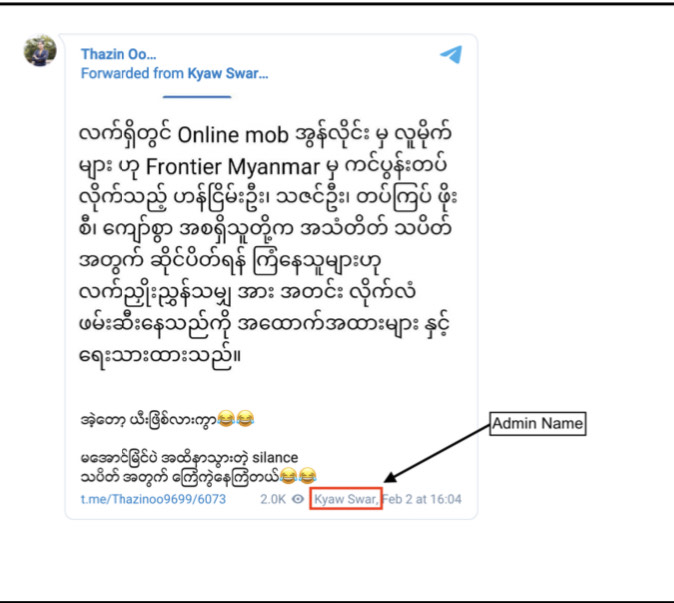

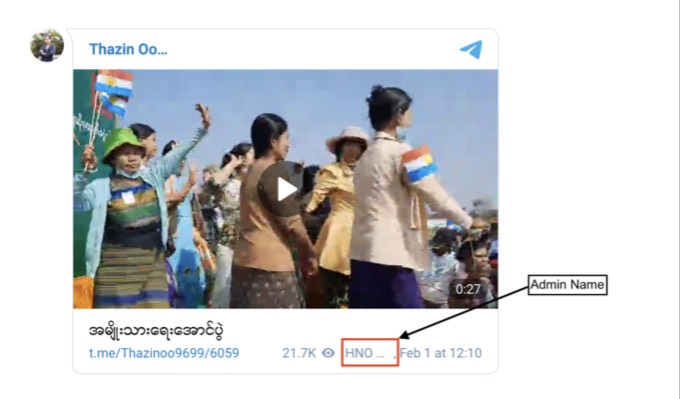

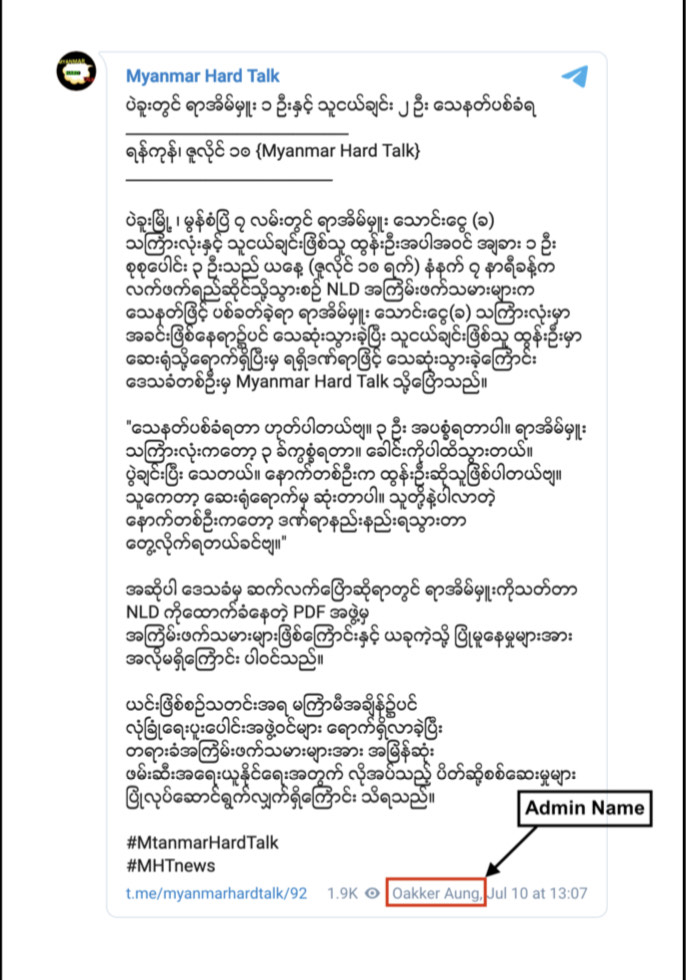

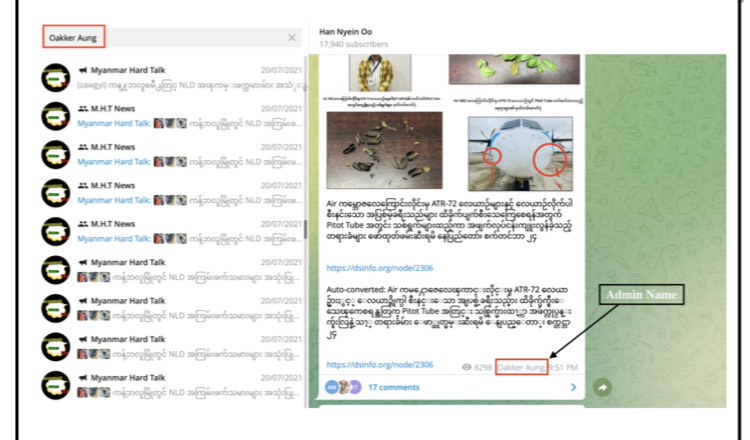

Screenshots showing shared admins across multiple pro-military Telegram channels (supplied)

A coordinated campaign

There is mounting evidence that the Telegram accounts are part of a coordinated campaign and are directly linked to the military and its institutions.

On the morning of February 7, the now-banned Han Nyein Oo account posted about police Major Tin Min Tun, who had defected in February of last year, complaining that the police officer remained at liberty. According to local media, police in riot gear stormed Tin Min Tun’s home in Yangon’s North Okkalapa Township later that same day and seized his property (he was not home at the time of the raid).

Some Telegram channels also show which admin made a specific post, giving insight into the connections between different channels. For example, one post by Myanmar Hard Talk was written by an admin named Oakker Aung. The same username is also listed as an admin for one of Han Nyein Oo’s pages. Myanmar Hard Talk is a political commentary operation that revolves around an inflammatory talk show and social media posts, often hosting extremist and controversial figures. Hardline nationalist Maung Myint, a candidate for the military proxy Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), was a regular guest in the lead-up to the 2020 election.

Myanmar Hard Talk was banned from Facebook following a Frontier exposé that showed the page was spreading disinformation and anti-Muslim hate speech. The network has since resurfaced on Telegram, where it has accumulated nearly 19,000 followers – in August of last year, it had just 6,000 subscribers. While its growth has been substantial, it still doesn’t compare to Facebook, where it accumulated 240,000 followers in around 11 months before being shut down.

Thazin Oo was another account that participated in the campaigns to arrest business owners and soldiers, which was also recently deleted, but a new channel has already accumulated more than 11,000 subscribers.

While most pro-military channels hide their admins, Thazin Oo’s channel did not. A number of her posts were written by admins HNO – a name regularly used by Han Nyein Oo, including for one of his accounts – and Kyaw Swar, another prominent pro-military Telegram user with around 53,000 subscribers on the messaging app. In a post on March 9, Kyaw Swar targeted a prominent activist who recently criticised Telegram, posting her supposed address in Yangon. That account remains accessible.

Thazin Oo has direct connections to the junta and the proxy USDP. She frequently campaigned for the USDP before the 2020 election, even appearing in a video posted by one of the party’s verified Facebook pages days before the election. The same page would go on to spread disinformation claiming that the 2020 election was undermined by massive voter fraud – an allegation for which no credible evidence has been produced, but that was used as a pretext for the coup.

Since the coup, Thazin Oo has appeared as a presenter for the military’s official television channel, Myawady TV, as well as for Myanmar Hard Talk and a pro-military tabloid called Thuriya Nay Wun (known in English as Sun Rays).

Thuriya Nay Wun is run by journalist Moe Hein, who wasn’t always known as a military sympathiser. In 2013, he angered the USDP government and businessman Tay Za by writing an article critical of military cronies, calling for them to “jump into the Andaman Sea”. The Irrawaddy reported in 2014 that he was an American citizen and was banned from returning to Myanmar at the time.

But today, Moe Hein shares a steady stream of pro-military propaganda on Telegram, and also appears regularly on Myawady TV. He was even among a list of channels that Han Nyein Oo urged his followers to also subscribe to.

Spreading slander

Han Nyein Oo’s list also included Telegram users BaNyunt and Sergeant Phoe Si. Both have targeted so-called “watermelons” and are also participating in another campaign to undermine defecting soldiers. They and other social media users are spreading unsubstantiated rumours about defecting soldiers, seemingly in an attempt to discredit their reputations or claim they were kicked out of the military rather than having deserted. The posts often included homophobic or misogynistic claims about their sexual behaviour.

In one post, a Facebook user claimed that a female soldier who defected had slept with her married superior officer while his wife was pregnant.

On February 7, another pro-military user wrote that a defecting soldier “started his service only yesterday and pretends to know a lot about the Tatmadaw”. The post claimed the soldier was a “trainee” and was punished for sneaking out without permission. He accused him of being a gambler, drunk and womaniser who was in debt. But other defecting soldiers told Frontier the man in question was a lieutenant, an officer position that typically takes years of service to achieve.

Kaung Thu Win, the captain who defected, was also targeted. In a post on January 10, a Facebook user claimed he was a homosexual drug user. The Facebook user only has 3,300 friends, and the post only received 180 reactions. But that same day, it was also shared by Sergeant Phoe Si and BaNyunt on Telegram, where they have over 27,000 and over 23,000 subscribers respectively. Both channels remain accessible on Telegram.

“Once you leave the army, you will be attacked online… I already knew in advance,” Kaung Thu Win told Frontier, adding that he and his wife “are still laughing” at the slander.

Kaung Thu Win said the military spreads disinformation to try to “create a misunderstanding” between defecting soldiers and the people. He claimed there is a special taskforce in Nay Pyi Taw dedicated to psychological warfare called the Tatmadaw Technology and Information Force. Frontier could not independently verify this claim, but in 2018 the New York Times reported that hundreds of military personnel were involved in anti-Rohingya social media campaigns. That article also said members of the team were based in military compounds in Nay Pyi Taw.

Narratives discrediting defectors have also been spread in state media. The junta’s information minister recently told reporters that stories of defecting soldiers are “exaggerated”. He also called them “cowards who did not dare to admit their guilty moves in breaking the law”.

Kaung Thu Win said it has also long been a military policy to monitor the social media accounts of soldiers.

“Before the coup, soldiers and their children had to give their accounts to the army. You have to attach your Facebook name and personal code number … All of our superiors have to give it to their superiors,” he explained. Kaung Thu Win said that those speaking out or leaking information should use a new account on a different phone.

Kaung Thu Win also called for Telegram to take more action to control dangerous content.

“I hope this company does not want to hurt anyone in any country. They created Telegram so that people could use it safely. But now that people in Burma are suffering because of Telegram’s lack of control, they should reconsider,” he said.

Wai Phyo Myint with Access Now said the strategy seems to be to inspire fear within the military system and within society at large. She said in the beginning, the Telegram channels were mostly targeting high-profile politicians and activists, but they are increasingly targeting average people opposed to the military. This includes posting their home addresses and even the names of their children.

Wai Phyo Myint said many in Myanmar are now constantly scanning these lists, which also takes a mental health toll.

“This is on a daily basis, these posts. We have to go and regularly check these channels just to see whether we or anyone we know are on this list,” she said.