A state-owned bank’s cap on lending to farmers is being blamed for contributing to distress and costly disputes amid calls for it to be scrapped.

By KYAW YE LYNN | FRONTIER

WHEN U SHWE Oke Htote decided to build a two-storey home in a remote village of Ayeyarwady Region in 2015, he did not anticipate any difficulty finishing the project.

“We had saved money to build the new home, but the amount was enough only for the foundations and some other work,” said Shwe Oke Htote, 45, who farms about 12.5 hectares (31 acres) of paddy land at Phoe Kyar Ai Village in Ngapudaw Township, with his wife Nan Mone Tine. “We were hoping to finish it completely in three years.”

Three years later the house stands unfinished, with the upper storey incomplete. “We are not able to continue the building work because of a lawsuit,” the farmer told Frontier on July 4.

The lawsuit was filed at the township court in late 2015 by a woman named Nan Kee, who says 3.6ha (nine acres) of the land belongs to her.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

She is the former wife of Mone Tine’s uncle, U Shwe Phar, who had lived with his niece and Shwe Oke Htote for 15 years until he died in late 2015.

Shwe Oke Htote and Mone Tine say that the first time they met Nan Kee was at the farm after Shwe Par died.

“She appeared shortly after U Shwe Phar died. She asked us to return paddy land that we registered with his name,” he said.

“We bought that nine-acre farm with 600 bags of paddy in 2009. It is not U Shwe Phar’s,” he said.

The purchase was conducted traditionally in the presence of village elders. It was not registered and no contract was signed.

“The whole village knows how we struggled to buy it,” said Shwe Oke Htote.

A factor in the situation confronting Shwe Oke Htote and Mone Tine is the acreage limit on government loans to farmers. Each year, state-owned Myanma Agricultural Development Bank disburses large sums in the form of short-term loans to farmers for their monsoon and winter season crops. MADB has been providing the loans since it was established in 1953, but they are limited to 10 acres for each farmer, no matter how much land he or she owns.

In 2013, the government allowed farmers to register their farms under the newly introduced Farmland Law and access larger loans from MADB. Shwe Oke Htote registered land under his name and that of his wife and Shwe Phar in order to circumvent the 10-acre limit.

Mone Tine told Frontier that Nan Kee left her uncle decades ago and has adult children from a second marriage.

“Even if it is my uncle’s farm, I don’t think she owns it,” she said.

Three years on, the case is yet to be resolved and more charges and counter charges have been laid.

Shwe Oke Htote said the village tract-level Farmland Management Committee had decided, on the grounds that he had been farming the land for years, that he had the right to continue to farm the disputed land until the court issued a verdict.

“The first charge against her was when she harvested paddy that I grew on the disputed land in 2016,” he said.

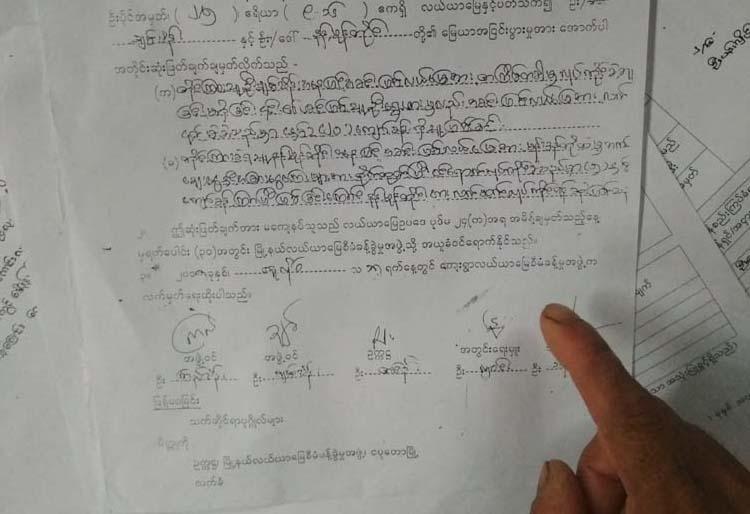

A document from the local Village-tract Land Management Committee. (Kyaw Ye Lynn | Frontier)

The two parties have brought a total of five charges against each other – three against Nan Kee and two against Shwe Oke Htote – as well as the disputed land case. Shwe Oke Htote was detained for a week by police, while Nan Kee was on remand for nearly three months before she was released on bail.

“As the court hearings are continuing, I have to travel to Ngapudaw almost every week,” he said, adding that he has spent about K10 million since Nan Kee filed the land dispute case.

“Honestly, I don’t want to own that farm anymore. It is only worth about K3 million, but I will have to fight for our rights.”

Nan Kee alleges that Shwe Oke Htote is trying to possess the land unfairly and illegally.

The land was given as a wedding present by Shwe Phar’s parents when they married, she told Frontier on July 18.

“We had been farming it since we got married when I was 18. Our divorce was not done officially, so I or my eldest son should have the right to inherit it when my husband died,” she said.

Nan Kee is being assisted by U Khin Nyunt, an activist with the 88 Generation Peace and Open Society in Ngapudaw, who said Shwe Phar had allowed his niece’s husband, U Dan To, to farm the land in dispute.

According to Khin Nyunt, when Dan To’s wife died in 2013, Dan To owed Shwe Oke Htote 100 bags of paddy. Shwe Phar permitted Shwe Oke Htote to farm the land for three years to write off Dan To’s debt, the activist told Frontier on July 18.

“When U Shwe Phar died in 2015, his son asked U Shwe Oke Htote to hand over the land, but he refused. Instead, he offered to accept compensation of K900,000,” Khin Nyunt said.

“Both sides are suffering from this ongoing case; we are urging them to negotiate instead of fighting at court,” he said.

Costly, lingering disputes arising from the registration of multiple names to secure more agricultural loans are creating tensions in farming communities throughout the country.

U Myint Naing, an activist with the Association of Human Rights Watch and Defence, based in the Ayeyarwady Region capital, Pathein, said the practice is common among farmers countrywide.

“Due to the MADB’s policy, a farmer can have a maximum loan for 10 acres. So they use this way to get more loans by bribing village-level officials,” he told Frontier on July 18.

The bribes are necessary because to apply for land ownership, farmers need a recommendation from the village administrator, Settlement and Land Records Department and village-tract Land Management Committee.

U Thein Win, manager of MADB’s Research and Training Department, said there had been no change in acreage limit since 1953. He said that although the loan amount had been increased this year to K150,000 an acre, up from K100,000, last year, it would not be enough to meet all of a farmer’s costs, which are around K200,000 an acre.

Thein Win told Frontier on July 18 that the loan amount was increased each year based on two factors: the percentage of farmers who had repaid their loan the previous year and the amount MADB is allocated by state-owned Myanma Economic Bank.

Myint Naing said MADB loans should not be limited to 10 acres, but to the size of a farmer’s land.

“The loans should also be provided before the farming season starts,” he said, adding that loans for the current rainy season were yet to be disbursed in some areas.

“When the loans are not provided in time, farmers have to borrow at high interest rates from loan sharks. When they receive the MADB loan, they repay the loan sharks,” he said. “This happens everywhere in Myanmar.”