A lack of information about courses makes it hard for students to make informed choices as they negotiate the lengthy process of getting admitted to university.

By EAINT THET SU | FRONTIER

ON JUNE 8, more than 850,000 students who had just finished their final year of school received their matriculation exam results. It’s a nerve-wracking time for the many thousands of girls and boys who hope their marks are high enough to be admitted to the university course of their choice.

Almost 270,000 students, or just under a third, passed the matriculation exam this year, and competition among them for admission to sought-after disciplines such as medicine is, as ever, fierce.

But are they making the best choices? And what factors inform those decisions?

Interviews with students and a survey conducted by Frontier indicate a lack of information and advice about available university courses, and about the career paths that are open to students.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Students also can’t expect much guidance as they negotiate the formal process for university admission, or even basic information about the steps that need to be taken.

Step by step

Each year, the process begins in the first weekend of June, when lists showing how students performed in the 10th grade exams in March are posted outside their high schools. In the crowds gathered around the lists, the biggest smiles belong to students who have been awarded enough distinctions to gain admission to their preferred course.

About a week after the results are posted, students are required to obtain a copy of their individual marks from the regional head office of the Department of Myanmar Examinations. These papers show a student’s total score from the six matriculation subjects; each subject is marked out of 100, giving a potential maximum of 600. All students study Burmese, English and mathematics, while the other three subjects vary depending on whether the student is in the science, science-arts or arts stream. A mark of at least 80 is needed for a distinction in the science subjects but for Burmese and English this is reduced to 75 because it is generally harder to gain top marks in the exams for these subjects, which include longer essays.

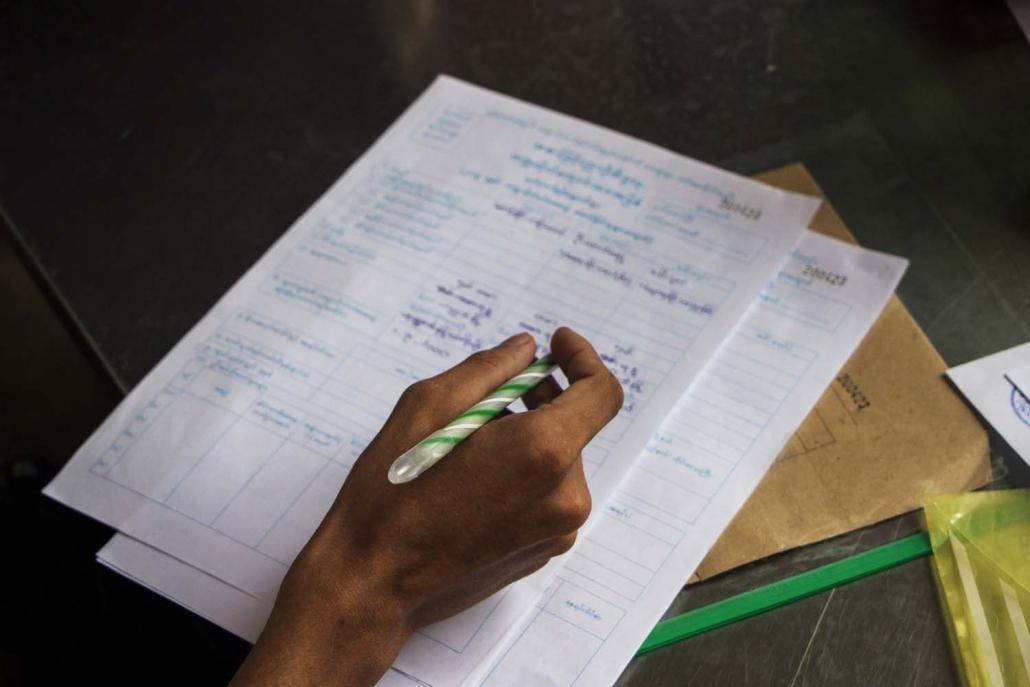

The next step in the process is for students to return to their former high school in June or July to collect a university admission form. This form requires students to list up to 20 university courses in descending order based on preference. They have to return the completed forms at a designated university in their nearest town – Yangon University for students in Yangon Region – where they often have to queue for hours. The forms are then forwarded to the boards of the different universities.

Universities are then free to pick the highest-scoring students for the limited number of places on their courses; an individual student’s chances depend less on the exact marks they receive in their matriculation exams than how their marks compare to other applicants. Even if a student has been awarded distinctions in each subject, it is still possible that they won’t be admitted to their preferred course.

Girls, who tend to perform better in the exams, need to gain higher marks than boys to be admitted to certain courses because universities want equal numbers of male and female students. For instance, to study medicine, a girl typically needs an overall score of about 510 while a boy might only needs a score of 490.

Students study after a lecture at Yangon University. Little information is made available to matriculation students about the contents of university courses prior to enrolling. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

The information gap

There is a lack of information publicly available about the 150-plus government-administered universities and the courses they offer, which limits the ability of students who are eager to attend university to make a meaningful choice.

Secondary students are generally told very little at school about universities, their courses, facilities and academic staff, or about career opportunities.

Frontier conducted an online survey of people who had attended a state university and received 63 responses, of which 50 were from current students. The survey asked about their experience of the university admission process and the information they used to decide which courses to apply for.

Many students are not admitted to their first choice of university, as was the case with 37 respondents, or 60 percent of those surveyed.

Asked how they initially learned about the university they ended up attending, 73 percent said the information came from their family or close associates.

Respondents were also asked how many universities they were aware of when completing their admission form. Two thirds – 42 respondents – said they knew five universities or less, while 13 respondents said they knew only one.

Nearly two-thirds of respondents – 41 altogether – said they only later became aware of universities that might have been a better fit for them, by which time it was too late.

Only seven of the 63 respondents said they learned about their institution from advertising, of whom four attended a private university. One had enrolled in a new major at Yangon University, microbiology, that was launched and promoted mainly through Facebook.

The information gap also includes a lack of guidance on taking the multiple steps of the admission process described above. Half of the students surveyed said they had to “ask around” to find out which government department to visit for documents and the deadline for submitting applications.

Students who passed the matriculation exam fill in the university admission form at Yangon University in Kamaryut Township on June 27. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

A leap in the dark

Ma Thinzar Htet, a second year student at Yangon Technological University, had turned to the internet when trying to decide which university to attend.

“I had no information about which university would suit me and there was no one I knew to ask,” recalled Thinzar Htet, who is now 18. “There’s a guide book about universities in Myanmar but it only has the university name, entrance mark and some basic rules for each university; it’s not enough,” she said. “I had to rely on Google to search for the major streams that I was interested in and [based on that] I made Yangon Technological University my first choice.”

Thinzar Htet achieved marks sufficiently high to be accepted by YTU, which is regarded as one of the country’s most prestigious universities.

After receiving a letter of admission from the university, she had to decide on a major and chose electronic engineering, which she knew little about but thought would be interesting.

During the first semester of their first year at university, students are permitted to change their major if they’re unsatisfied with it, subject to their matriculation scores being high enough, relative to other students, to enter the new course. However, here, they tend to encounter the same information barriers; for many students, the course switch is a leap in the dark.

By the time the deadline to transfer to another course came around, Thinzar Htet still had little idea whether she’d made the right choice of major. She said the first-year curriculum was similar to the grade 10 advanced science course that she’d studied in high school.

“We didn’t learn anything about the major during the first year,” she said. “We only started learning about our major subjects in second year, but by then it was too late to transfer if we found we didn’t like it.”

It would make sense to offer students more opportunities to explore the full range of majors on offer at universities, and also make counselling available to help them decide what course was best suited to their abilities and interests. The absence of such counselling sets Myanmar’s higher education apart from that of many other countries. But even simpler changes could help. If universities put information about the content of their courses online, prospective students could see what they’d actually be learning.

Students who passed the matriculation exam fill in the university admission form at Yangon University in Kamaryut Township on June 27. (Thuya Zaw | Frontier)

Studying from a distance

Of the 41 students surveyed who said they were taking outside classes, only six said these classes were related to their university studies; the rest said either that they were to boost their future job prospects or “both”.

This situation is particularly common in the distance education system. As of May 2012, more than 60 percent of the 471,000 students enrolled in tertiary education were studying off-campus.

Distance education students are required to attend 10 to 15 days of classes before their examinations, leaving them ample time to undertake other courses that may lead to job opportunities before they graduate. However, the majors they choose might not reflect their career choice; in fact, it seems many distance students don’t particularly mind what they study. Because many employers require job applicants to have a university degree, distance education simply helps students tick a box rather than gain knowledge that will help them in the future.

Ma Phoo Myat Thwe, who recently finished the first year of a distance education course, is one such example. After completing grade 10 and sitting her matriculation exam in Meiktila in Mandalay Region, she moved to Yangon to attend English language classes.

“I wanted to do a business management major at the National Management Degree College but my scores were not high enough and I was admitted to do a tourism major instead,” Phoo Myat Thwe said.

“Because I wanted to study business, I declined doing a tourism major at NMDC and did a business major at a private university,” she said, referring to Strategy First University in Yangon’s Sanchaung Township.

But because private college degrees are not recognised by the government, she also enrolled in a distance education course. “A degree from a recognised local university is required for any kind of job you do,” she said.

Phoo Myat Thwe was keen to use it as an opportunity to study psychology, something that had always interested her. However, her mother made her choose English instead, she said. “There is pressure to choose a major that corresponds with your marks. It’s difficult to make adults understand that you want to choose what to study based on what you’re interested in.”

Studying for two degrees at the same time wasn’t a problem for Phoo Myat Thwe; distance education students tend to have a lot of time on their hands. Ten days of preparation classes are allocated before exams but Phoo Myat Thwe said she could only remember attending about three days of such classes as well as about 10 days of tuition during the academic year. Often, she would study a subject for a day before the exam and was still able to pass.

“Taking classes outside provides you with actual career-related skills,” she said. “I’m not sure that a distance education is useful for pursuing a career.”