Smuggling is costing the government heavily in lost revenue; poor enforcement means that for every 5,000 cans of beer brought into the country illegally, only one is seized.

By THOMAS KEAN | FRONTIER

THE ANTI-Illicit Trade Forum did not begin like your typical conference or workshop.

When Minister for Planning and Finance U Soe Win and Auditor General U Maw Than walked through the doors of the MGallery Hotel in Nay Pyi Taw for the September 19 event organised by EuroCham, they were whisked into a side gallery rather than the VIP seats or the lectern.

The minister and other senior government officials were immediately confronted by shelves of beer: more than 100 different products, in a range of colours, shapes and sizes. The beer shared something in common: all of it had been smuggled into Myanmar and was being sold openly in shops and markets.

The display included the usual suspects but also more obscure products like Fort Knox, a 19 percent alcohol by volume brew of indeterminate origin that comes in a liver-destroying 500-millilitre can.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Smuggling often conjures up images of furtive shipments across remote borders. The display reinforced the fact that in Myanmar, smuggling takes place relatively openly. Also on display were poster-sized images showing crates of beer being openly smuggled across land borders in trucks. One of the products on the shelf was a beer brewed in China’s Yunnan Province, but in a can covered in Shan writing. That a product would be produced specifically for illicit export into Myanmar suggests it is not difficult to smuggle beer across the border.

Once in the country, it is sold with impunity. The posters at the forum also showed examples of promotions and branding for Thai brands such as Chang and Singha. Together with Leo, another Thai beer, they are thought to account for up to 95 percent of the illicit trade, market research firm Euromonitor estimated in 2017 based on store checks in several cities. They are so prevalent that they even face competition from counterfeits like “Cheng” and “Leort”, which look almost identical to the real thing.

The exhibition also included stands displaying other commonly smuggled and counterfeit goods, such as whisky and cigarettes, as well as products that get less attention: consumer goods, bread improver and yeast, and flowers and seeds.

If the effect was to emphasise the scale and breadth of illicit trade in Myanmar and the impunity with which it takes place, it seemed to work.

When Soe Win took the stage a few minutes later, he spoke of the government’s commitment to tackling illicit trade. It had recently formed an Anti-Illicit Trade Steering Committee, headed by Vice President U Myint Swe, and the Ministry of Planning and Finance had instructed the Customs Department to propose short and long-term plans for tackling the problem, including setting up new checkpoints, conducting surprise checks and introducing a bonded warehouse system.

But then he paused, and went off the cuff.

“Before I conclude, I would like to say I’m rather amazed to have a look around the stalls here about the illicit trade which has been penetrating into our system. I think that it’s just the tip of the iceberg and I promise that this matter will be attended with serious consideration.”

The scale of the challenge

But the scale of the challenge is considerable, as illustrated by research that EuroCham commissioned Myanmar Market Research & Development to undertake that was presented at the forum.

The study estimated that total illicit trade in 2017-18 was nearly US$6.5 billion.

But MMRD research director U Aung Min acknowledged that this figure – derived from calculating the difference between Myanmar’s recorded imports, and what other countries’ customs departments report as being exported to Myanmar – is likely to be many times below the real figure.

For example, it doesn’t take into account items that are smuggled out of Myanmar through legal checkpoints, such as agriculture products, or the trade in illegal products, such as wildlife and drugs. It also doesn’t include trade at the dozens of illegal border crossings.

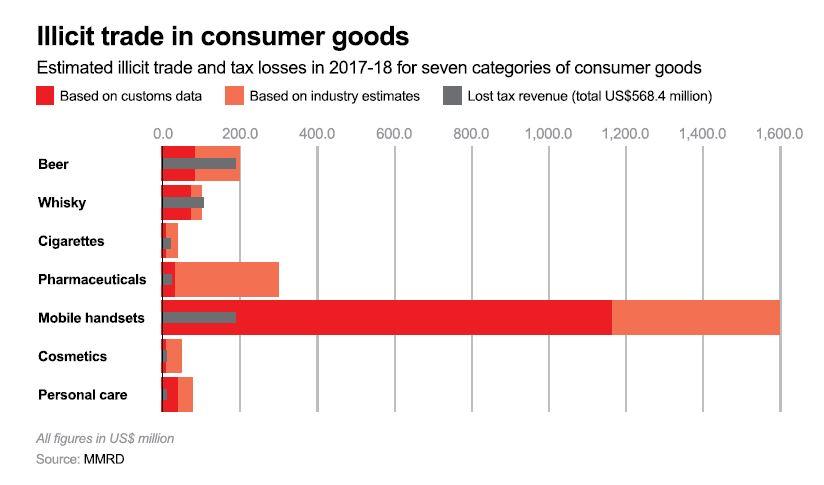

The study also examined seven consumer products – beer, whisky, cigarettes, pharmaceuticals, mobile handsets, cosmetics and personal care products – and found that the customs data showed a $1.427 billion gap between recorded imports and exports, about 22 percent of the $6.5 billion estimate.

But industry experts and market players estimate that unrecorded illicit imports of these products – such as some of the beer on display at the Anti-Illicit Trade Forum – account for perhaps another $943 million each year, for a total of $2.37 billion.

At current tax rates, this smuggling costs the government $570 million a year in lost revenue.

Enforcement is almost non-existent. In terms of value, seizures accounted for just 0.4pc of estimated illicit trade, and far less for the seven consumer products included in the survey – about 0.02pc. That means that, on average, for every 5,000 smuggled cans of beer, only one would be seized.

illicit_trade_in_consumer_goods.jpg

Fuelling conflicts and crime

Who benefits from this illicit trade?

Mr Troels Vester, country representative from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, said that in the past illicit trade was considered a “soft crime” and had “not been given the attention [it] should have”.

It has also expanded in scope, he said, referring to a display showing smuggled flowers and seeds. “[Before today] I didn’t know about flower seeds being smuggled, for example,” Vester said. “Before it was luxury goods, now it is everything.”

Vester emphasised that illicit trade is not just “a tax issue … it’s certainly bigger than that”, citing as an example the health effects of consuming counterfeit pharmaceuticals.

This trade is also closely intertwined with Myanmar’s long-running conflicts. Much of it passes through border crossings run by ethnic armed groups, providing a lucrative source of income that only serves to fund conflict.

The smuggled products include the precursor chemicals that have helped make Myanmar – and Shan State in particular – a global centre for the manufacture of methamphetamines and other synthetic drugs, which are exported throughout the region and sold in relatively high-value markets such as Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

The UN estimates that methamphetamine trafficking generates between $30.3 billion and $61.4 billion a year, making it the most lucrative business for transnational organised crime groups in the region.

The illicit trade in licit goods, such as beer or cigarettes, is undoubtedly a far smaller earner than drug trafficking. But in many cases it is the same groups that are benefiting.

“We have seen over the last years that the issue of illicit drug production and illicit goods is very interconnected. We’ve seen payments between different groups using different modalities and items,” Vester said. “It’s not separated and this is important to understand in terms of how to deal with it. This is transnational organised crime.”

While reining in the activities of those responsible for illicit trade is a major challenge, the government can introduce policies that make smuggling more difficult, reduce consumer demand for smuggled goods and make it easier to do business legally.

Many pharmaceutical products are smuggled into Myanmar, for example, because getting Food and Drug Administration approval to import them legally is complicated and time consuming. Foreign liquor is smuggled because there are no legal avenues for it to be imported and distributed to retailers. In other cases, high taxes encourage illicit trade.