An absence of policing, increased narcotics production, widespread trauma among youths and Myanmar’s economic collapse have created a perfect storm for rampant drug dealing and use.

By FRONTIER

At a nightclub in Yangon’s Ahlone Township, a young man hands a 1,000 kyat tip to a waiter and asks for an empty plate. When the waiter returns, a group of four men and two women openly cut and snort lines of ketamine, a powerful anaesthetic commonly used on animals, under dazzling laser beams.

Before the military coup, this club was just like any other night-time entertainment venue – a place for Yangon residents to drink and dance away stress after a long work week.

“I used to come here often and it was very different from now… Last year I was a low-key user, but things have changed and now you can easily get ahold of these drugs”, the young man, Ko Zaw*, told Frontier.

Ko Zaw and his friends are among a large number of Yangon residents increasingly turning to street drugs as a means of escaping the city’s post-coup reality. Myanmar’s cartels, the world’s largest producers of synthetic drugs, are operating with greater impunity than ever, tapping new markets in cities where police are more concerned with revolutionary activity.

Ko Zaw said it is now possible to buy ketamine directly from the club’s waiters, at a slightly higher price.

“Just like that – It’s now a one-stop shop!”

A doctor and the founder of a Yangon-based organisation helping victims of drug addiction told Frontier that he was dealing with an alarming rise in young patients since the February 2021 coup. Security forces responded to mass protests by slaughtering hundreds of civilians, sparking a broadening civil war, while erratic policy decisions collapsed the economy.

“After the military coup last year, all these young people had their dreams dashed and lost their ambition. Combine that with an extraordinary drop in the price of these drugs – they use it to find some relief,” the doctor said.

A licence to sell drugs

The ready availability of narcotics, and the highly visible increase in their use in Myanmar’s major cities, is a symptom of both the nationwide collapse of governance and a ramping-up of drug production in the country’s border regions.

During the previous administration, petty drug use among young people in Yangon was curbed by a campaign launched in 2018 by the military-controlled home affairs ministry that encouraged people to become whistle blowers, with authorities offering informants large cash rewards. Analysts have also noted that, despite strong opposition, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s administration attempted to limit the power of those pulling the strings of Myanmar’s drug trade, efforts which have now been reversed.

In the months immediately preceding the coup, Chinese triad groups operating in the Greater Mekong region began a rampant expansion in the narcotics production. These groups have historically dominated the drug trade in Myanmar with the acquiescence and active participation of certain ethnic armed groups, military-aligned Border Guard Forces and individuals backed by the Tatmadaw.

Recent entrants, typified by gangster Wan Kuok-kui’s 14K Triad and She Zhijiang’s Yatai International, have spread the tendrils of Chinese organised crime deeper into Myanmar’s border lands.

The presence of such gangs on Myanmar’s border has made it easier for groups to access inputs crucial to the production of synthetic drugs. Key among these are precursor chemicals that enter Myanmar from China, either as mislabelled commercial chemicals or smuggled in unmarked containers.

These chemicals then “disappear into eastern Shan State under the control of the [United Wa State Army] and other insurgent groups,” Mr Michael Brown, former US Drug Enforcement Administration attaché to the Myanmar government from 2017 to 2019, told Frontier. The UWSA is Myanmar’s most powerful ethnic armed group, which controls two autonomous enclaves on the Thai and Chinese borders, and has long been accused of involvement in the narcotics trade.

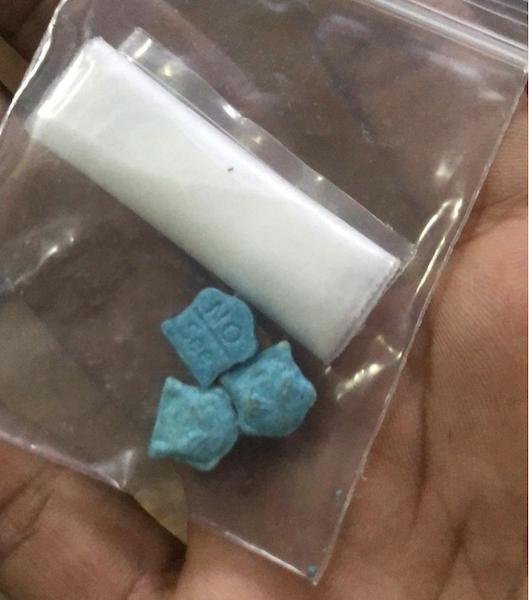

Yaba, known as WY in pill form, is a stimulant powder containing methamphetamine and caffeine, which has fast become Myanmar’s most lucrative drug product. The pills are produced in their trillions in jungle labs throughout eastern Myanmar and exported to Asia and beyond.

“Traditionally, in Shan State and across the neighbouring Mekong, you see big shipments of tablets with branding and logos trailing back to the Wa, [the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army] and [the National Democratic Alliance Army]… but there was a big push by smaller armed groups and militia producers after February 2021,” said Mr Jeremy Douglas, Regional Representative of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime for South East Asia and the Pacific. The MNDAA and NDAA are two other ethnic armed groups that operate in Shan State and are closely allied with the UWSA. Like the Wa, the NDAA controls its own autonomous enclave on the Chinese border called Mongla, while the MNDAA lost its main Kokang territory to the military in 2009.

Douglas said production by groups smaller than the UWSA, MNDAA and NDAA has increased by at least four times in the past year.

“They typically don’t produce their own yaba powder, but they have territory and tablet presses… they most often source in bulk from the Wa and big labs, and then they do production runs,” he said.

With production both rampant and unconstrained, post-coup conditions provide fertile ground for an upsurge in domestic drug use. It’s an open secret that many of Yangon’s most popular night spots are operated by people with direct links to the Tatmadaw or Myanmar’s ethnic armed groups, and they have long provided a convenient means of both raising and laundering drug revenue.

Registration documents from Myanmar’s Directorate of Investment and Company Administration show that two of Yangon’s busiest venues – Pioneer and Crush Bar – are owned by Bon Myint Entertainment, a company founded by San May and her husband Aung Hein (it is unclear if the pair are still married). San May is the third daughter of Bao Youxiang, commander-in-chief of the UWSA.

A source told Frontier that, as with many other venues, drugs could be bought directly from the nightclubs’ waiters, and despite the military’s imposition of a curfew on Yangon between 12am and 4am, both venues remain open and busy during that time.

Many venues now offer users private rooms, costing between K50,000 ($15.50) and K200,000 ($62.50), to capitalise on the drug boom. In Yangon’s KTV’s, many of which have always run a hushed trade in narcotics, the most popular options are ketamine, yaba and happy water – a cocktail of powdered caffeine, diazepam, ketamine, ecstasy, methamphetamine and tramadol which is served in a large bowl. Happy water is now so ubiquitous, that a sachet was recently accidentally consumed by a monk and his lay servants in Tachileik.

“After the military coup, all the KTVs, which have been around since the last government, are allowed to operate with impunity, regardless of curfew. Most of them are now paying the military government,” another former US DEA agent familiar with the situation told Frontier.

“I think we’re back to the days where the trafficking groups from Shan State and other border areas are allowed to operate as long as they pay taxes [to the junta],” he added.

Drug production highs meet economic lows

Ko Jeffrey*, a 30-year-old small-time cannabis dealer living in Yangon’s Sanchaung Township, says he’s surprised by how much his business boomed after the military takeover. At the time, he said the price of a WY pill was around K1,000 (US 85 cents in March of last year).

From March, the military intensified its violent crackdowns in Yangon, killing hundreds. The focus on suppressing any dissent, and the venality and underfunding of Myanmar’s security forces, has meant that the policing of drug crimes has since been overlooked.

Ko Jeffrey told Frontier that, while the open sale narcotics such as methamphetamine used to only be prevalent in mining township gem markets, such as Mogok in Mandalay Region and Hpakant in Kachin State, they are now prominent in black markets in central Yangon.

While previously only familiar faces could purchase drugs in such locations, dealers now run a lucrative open trade in crowded marketplaces like those found at Insein’s waterfront and in Dawbon Township. Heroin and crystal meth, known globally as ice, can now also be purchased across Yangon as if it were being sold legally, Ko Jeffrey said.

While the cost of fuel and basic goods has risen dramatically since the military takeover, the price of street drugs has slumped – at the time of writing, a can of Coca-Cola (K800, or US 25 cents) is almost twice the average price of a WY pill (K500, or US 15 cents).

“It does not matter where you look across the region, and particularly the Mekong, yaba is at record levels… and the reason it’s cheap is because there’s so much supply making it to the streets. Producers, traffickers and dealers have dropped the price to rock bottom,” Douglas told Frontier.

Some people arrested for possession of drugs told Frontier that they believed they were only detained so that police or soldiers could extort money from them, and many had been set free after meeting cash demands based on the type and quantity of drugs discovered.

They said that security forces at checkpoints where most arrests are made are more concerned with detaining anti-military activists and resistance force members.

“I was interrogated for two days because they [soldiers] found a picture of Aung San Suu Kyi on my phone. There was also a pack of 10 WY pills in my bag, as well as some weed. But they were not interested in the drugs,” said Ko Hein Thant, a 27-year-old resident of Thaketa Township who was accused of being a People’s Defence Force member.

“[The drugs] had been discovered at other checkpoints along the way, and I’d got to this point by paying K10,000 per gate,” he said.

But Frontier knows of at least one other case when a Yangon protester was arrested with demonstration materials and marijuana in his vehicle, and the regime was happy to pile on drugs charges to extend his prison sentence, which he is still serving today.

Stagnant economic growth and growing unemployment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and military coup has left the city’s youths unable to cope with rapidly rising prices. To many users, including Hein Thant, casual drug dealing now represents a low-risk way of making ends meet. He sells cannabis – which he says many dealers now feel comfortable growing in their own homes – but yaba has become his mainstay.

“I can buy a WY pill for K350 and sell it to my friends and other people for 1,200. It’s a piece of cake – I can get K30,000 to K40,000 a day, easily”, said Hein Thant, adding that, before the coup, users would pay no less than K2,000 per pill.

Seeking help

Although selling drugs in Yangon is no longer such a risky business, those working with users say that they are seeing more people fall prey to side effects and addiction.

“Most people who come here have problems with yaba, followed by ketamine. A lot are also using opium, so many have to be treated with methadone to reduce their cravings and withdrawal symptoms,” said the Yangon-based doctor.

Sources told Frontier that some young people who had begun dealing small amounts of yaba are progressing to the sale of more dangerous and addictive drugs like heroin, raising the drug’s profile among young people and leaving many mired in drug dependence.

Although always available in Myanmar, the world’s second largest producer of opium, sources said the street value of heroin has fallen to as low as K10,000 ($3) a gram since the coup. The same amount would cost a user in London or New York over $100.

“You can buy a bottle of kyin (liquid black tar heroin) for about K20,000 – in some places it’s 15,000,” said Ko Zwe, a drug user in Yangon.

“You can now pick up pills for no more than K1,000, but the purity is not the same as it used to be, and the side effects are far worse,” a long-time street dealer told Frontier under the condition of anonymity.

He said that nobody had tested the chemical composition of the latest batch of yaba pills being circulated in Yangon, and claimed to have personally experienced serious psychological damage, including hallucinations and bouts of severe depression.

“Since the military is not taking accountability for these people, I am certain that I will see many more people coming for help over the coming months,” the doctor predicted.

* indicates a pseudonym upon request for safety reasons