Among the throngs of demonstrators on the streets over the past couple weeks have been savvy street entrepreneurs selling revolutionary merch and inspired artisans and samaritans offering alms to protesters.

By FRONTIER

Few people on the streets of Yangon over the last couple of weeks seem to be happy with the military having seized power from a democratically elected government – save for a few truckloads of pro-military supporters – but the massive protests that have overtaken the city since have created unexpected opportunities for some.

After Tatmadaw chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing staged a coup on February 1, activists and aggrieved voters debated whether or not they should take to the streets. By the following weekend, the debate was settled: the protests were on, and they haven’t stopped since. Though there have been tense standoffs between protesters and police, downtown has often taken on a festival-like atmosphere. And no festival is complete without its artisans and merch vendors.

U Khin Myint, 57, used to sell purses and wallets on Anawrahta Street. But since demonstrators began flooding the area on February 6, he’s switched to selling protest banners and National League for Democracy flags and headbands.

“After the coup, no one was interested in my wallets or purses, so I changed,” he told Frontier. “And business is not bad.”

A vendor displays an NLD headband.

A woman waves an NLD flag.

A street vendor sells red ribbons to protesters in downtown Yangon.

He said each day he’s been selling between 100 and 150 headbands, which he buys for about K200 each and sells at his street stand for K300. On a day he sells 100, that’s a tidy K10,000 profit. NLD flags sell for between K30 and K50.

Daw Khin Lay, 32, who sells similar items near Sule Pagoda, said her income has risen since the protests began. Though she didn’t say what she was previously earning, she said she’s now bringing in between K20,000 and K50,000 a day. Still, that doesn’t mean she’s a fan of Min Aung Hlaing’s SAC.

“I don’t like the dictator, so I’m taking part in the protests by selling the protesters what they need,” she said. As if to assure Frontier she wasn’t seeking to exploit protesters, she said the bump in her earnings had been only “modest”.

The instinct on the street hasn’t solely been entrepreneurial. The cross-sectional and broad-based nature of opposition to military rule has also inspired acts of giving. One common feature to emerge at the protests is individuals and groups of people passing out free water and food – another among several signs of solidarity across large swathes of society and political groups at the demonstrations.

“Maybe they’re hungry, maybe they’ve come to the protest and haven’t had breakfast yet,” Ko Aung Naing Win, 17, told Frontier on February 8.He and his mother, Daw Mie Mie, 37, had just spent about K40,000 on bottled water and snacks at the City Mart supermarket at Aung San Stadium and were passing them out from a shopping cart on Gyo Phyu Street to marchers on their way downtown.

“We don’t accept this military coup, and we want our democracy back,” Aung Naing Win said. “They [the military] will do what they want, and there will be no future for us.”

A day later and a block away, local businesses were also joining in. A few doors down from the City Mart that Aung Naing Win and Mie Mie bought their water and snacks at, an advertising company had set out a table on the sidewalk stacked with water bottles. “Free water donation, anyone can take,” a sign on the table read. The message is bookended on each side by an image of the ubiquitous three-finger salute that has become the symbol of resistance to junta rule.

For others, charity is just another way to take part in the movement. Ma Myat Hnin Aye, 29, has been passing out snacks on the upper block of 35th Street during the protests. She called donating food to young people protesting against dictatorship itself a “revolutionary act”.

Artists join in

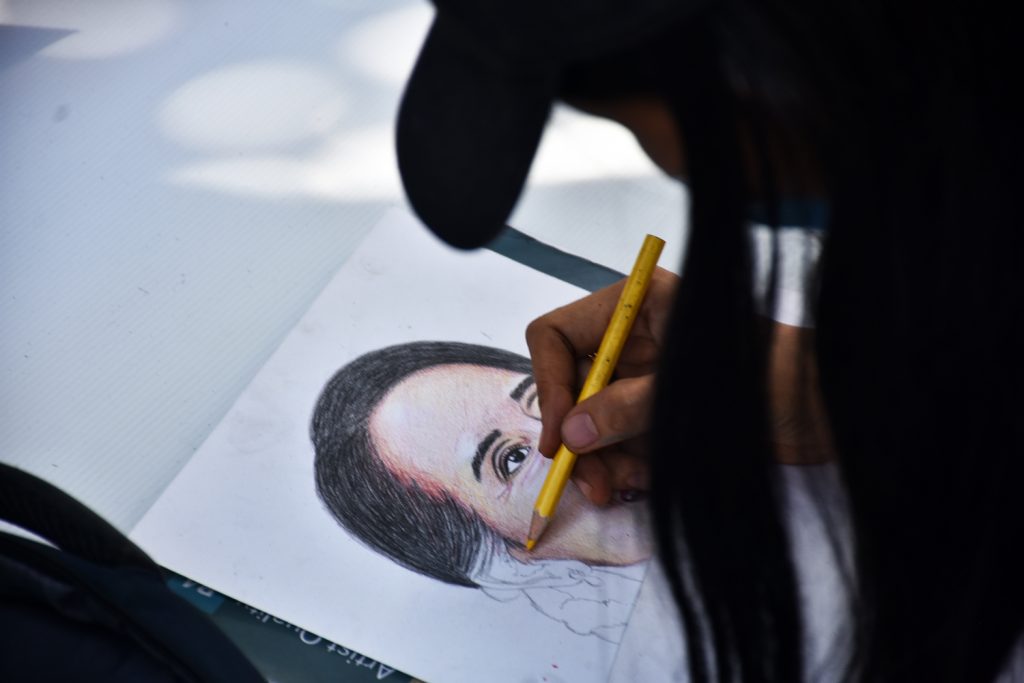

For several days during the protests, members of PEN Myanmar, the Association of Myanmar Contemporary Art, the Myanmar Poet Association and other art groups held poetry readings and a street exhibition along Pansodan Road in downtown Yangon. They sold paintings and original copies of hand-written poems and offered face painting to raise money for the Civil Disobedience Movement, wherein tens of thousands of civil servants have stopped going into work in protest against the junta. Government health workers, teachers, engineers, police, bankers, administrators and more have all joined in, crippling regular bureaucratic processes and the government’s COVID-19 response, among other programmes.

An artist sketches Daw Aung San Suu Kyi on Pansodan Road.

Saw Wai, a well-known poet and activist, told Frontier the exhibition was launched on February 7, after the artists and poets got together to discuss how to “participate in this revolution”.

“All proceeds from the exhibition will be donated to the CDM,” he said.

Prominent artist and former political prisoner Htein Lin was also among those exhibiting works at the makeshift gallery on Pansodan Road. On February 12, he read a dissident poem written by a friend who also took part in the historic 1988 pro-democracy movement.

“In remembrance of our colleagues from the All-Burma Students’ Democratic Front who perished, I wish to recite this poem,” he said:

He makes thousands of holes under the thrones of his enemies,

He cuts away the roots of his enemies.

Amongst the howls of haunting dogs and the sound of grub hoes

He saves his tribes by forging escape holes, and hides under the ground.

He never searches for fame in battles of the damned,

He salutes his colleagues who were inevitably oppressed by fate

He laughs silently from behind.

In fact, he is just a mole under the ground,

who does not fear living or dying.